Ng Yi-Sheng

On performance, queer activism, and speaking through the gag

Ng Yi-Sheng is a poet, fictionist, playwright, journalist and activist. He is the youngest winner of the Singapore Literature Prize (for his debut poetry collection, last boy). His second collection, Anthems (2014), consists of slam poetry works. His other publications include the bestselling non-fiction book, SQ21: Singapore Queers in the 21st Century, and a novelisation of the Singapore gangster movie, Eating Air. He also co-edited and Eastern Heathens: An Anthology of Subverted Asian Folklore. He has recently completed his MA in the University of East Anglia’s creative writing programme.

Divya: Listening to your performance of “A Poem for Mohan on Whoopin’ the Ass of his Bar Exam” at the Singapore Writer’s Festival was an extraordinary experience. The contrast between the uproarious poltical content and the calm early morning hours of a perfectly manicured international writers festival was not without its ironies.

The poem is studded with acronyms— the CBD (Central Business District), the MDA (Media Development Authority), the MRT (Mass Rapid Transit). These are iconic public institutions across the Little Red Dot that both corral and conduct our lives here. And there are other such flashes of recognizable emblems too— Speaker’s Corner, Parliament, the Penal Code, the Courts. They seem to frame the limits of the poem’s habitat and it is within this scaffolding that the minor and major dramas of difference churn: everything from the ban on chewing gum, debates around choosing the hijab, gathering in crowds, tipping cabbies, doing “unlicensed readings of an Elangovan play” and, of course, being gay.

So, let’s begin on this Little Red Dot— and all the ways in which your poetry draws the contours of its cultural map. How do these iconic institutions inform and influence your poetry and performance? What do they make possible and impossible, for you?

A Poem for Mohan on Whoopin’ the Ass of his Bar Exam (Recording)

Hey lawyer in your blazer and your G2000 tie,

Just tell me you’ll come out with me tonight.

Hey lawyer in your Gucci belt against your zippered fly,

I promise you an evening of delight.

We’ll book ourselves a bedroom suite in Hotel 81,

Call up our friends across the CBD.

And run a racket selling smuggled packs of bubble gum.

Hey lawyer, won’t you break some laws with me.

Yeah lawyer, won’t you break some laws with me!

We’ll watch a pirate movie that’s uncut by MDA,

We’ll eat and drink inside a crowded train,

We’ll hold unlicensed readings of an Elangovan play,

We’ll tip a taxi driver in the rain.

Let’s spill official secrets from our days in number four,

Let’s park like we’re disabled and for free,

Let’s gather in assemblies of five, six, or even more

Hey lawyer, won’t you break some laws with me.

Yeah lawyer, won’t you break some laws with me.

Hey lawyer, let me strip you of that Raul pinstripe shirt,

Your buckle’s such a pleasure to undo,

Hey lawyer kick those faux Armani shoes into the dirt,

We won’t need clothing where we’re going to!

We’ll start seditious blogs about religions we don’t like,

We’ll rant at Speaker’s Corner about race.

We’ll jia hong into Parliament on Kawasaki bikes,

Call SR Nathan lackey to his face.

Let’s distribute Jehovah’s Witness scriptures in the mail,

Spray Swiss graffiti on the MRT,

Convince some Muslim schoolgirls they should really wear the veil,

Hey lawyer, won’t you break some laws with me.

Hey lawyer, how we’ve tried to be such law-abiding men,

Hey lawyer, yet your body cries to mine,

Hey lawyer, since we’ve sinned already, let us sin again,

We’re criminals, let’s make it worth the crime!

You can listen to Ng Yi-Sheng perform "A Poem for Mohan on Whoopin’ the Ass of his Bar Exam" here.

Yi-Sheng: That’s an extremely broad question – after all, as a Gen X Singaporean, I could argue that every aspect of my being is a product of the state. We’ve had one-party rule since 1959, and the government’s social engineering policies have had a profound effect on all of us here.

And honestly, I’ve plenty to thank the government for. I was, after all, able to develop my poetry as a teenager through the Ministry of Education’s Creative Arts Programme, and the National Arts Council has funded my publications and my travels to literary festivals around the region. Yet I’ve also had to face censorship of my plays, readings and books by the Media Development Authority, and my friends have been jailed for contempt of court and illegal assembly when protesting against the People’s Action Party. The state made me educated and curious enough to see its injustice. It taught me language, and my profit on it is I know how to curse.

I should give a little background to this poem. It was composed for a poetry slam in 2011, when there was a constitutional challenge going on against 377A (Singapore’s anti-gay sex law), which my boyfriend actually did some pro bono legal work for. Poetry slams in Singapore are very liberating spaces, because you get three minutes on stage where you can just vent at a young, liquored-up audience and get instant gratification from their applause and laughter. It’s also a very localized space – I can expect fellow Singaporeans there to get my references – and an informal occasion, so I can experiment with form and not have to live down regrets if my poems don’t really work.

However, because I’m an activist, when I try and organise a literary reading, the MDA (Media Development Authority) specifically asks me to apply for a license. This doesn’t prevent the event from going on – although poems and stories have been censored before – but it is inconvenient, and it does show the strange way today’s Singapore both tolerates and curtails creative expression. Impromptu reading by non-political figures? Sure! Scheduled reading by known political figures, even if it’s held at a bookshop that holds non-licensed readings every weekend? Sorry bub, you’ve gotta submit your entire script and a list of the names and birthdates of everyone who’s going to open their mouths at the show.

Divya: The ‘poetic license’, as it were, is a complicated knot in Singapore. Could you tell us a more about what led you to start taking that license? Why did poetry become a medium for your activism? What were you reading/listening to during those early years that honed poetry (and particularly performance) into this tool for you?

Yi-Sheng: Why am I political in my poetry? At one point - say about four or five years ago - I realised I was one of the few consistently political spoken word poets in Singapore. Which was pretty bizarre: Although I'm gay, I come from a very privileged background, plus I'm male and majority-race Chinese. It wasn't a deliberate direction I took in my writing - it evolved pretty naturally.

I can think of two reasons why my poetry's like this. First, I studied in New York between 2001 and 2005. I'd already got involved in some elementary spoken word before that, thanks to some 1997 Singapore Writers Festival programs by UK poets Grace Nichols and John Agard, combined with numerous opportunities for poetry readings in Singapore, organised by Alvin Pang, Yong Shu Hoong and the like. But that was nothing like the packed-house, hip-hop-inspired, anti-war, anti-Bush rhymes of the Nuyorican Poets Café. I didn't write many spoken word poems during that period, but my image of what a poem could and should be was profoundly influenced by that scene.

The second big influence is drama. As a teenager, I got involved in playwriting in Singapore, attending theatre workshops and watching loads of locally written plays. And drama is the most overtly political of Singapore's art forms - probably because the mentor for many of our theatremakers was Kuo Pao Kun, a Mandarin/English-language playwright and director with roots in the belief that art should promote social change. So I came of age watching plays that fearlessly questioned Singaporean institutions, and had supper afterwards with artists who'd been trailed by the Internal Security Department on suspicions of anti-government conspiracy. So writing political poems was an obvious thing to do. I guess it's worth noting that there are now quite a number of other outspoken political poets, such as Stephanie Dogfoot, Nabilah Husna, Raksha Mahtani and Tania De Rozario. Their routes into political poetry are probably quite different.

The Right Hand (Recording)

The Right Hand

Build.

Progress.

Build language.

Build happiness.

Build language of religion,

Build people of religion.

Build

The language of happiness.

Build religion

And nation.

Build religion and society.

A society of people:

One nation, one progress.

Build religion and the language

of the democratic society.

Build happiness:

Our democratic religion.

The people of one religion of our society

build society of one religion on our society -

one nation based on people of our nation of our people

build a language, build a democratic language; our society as

Regardless.

We build,

Regardless.

We progress,

Regardless.

We race,

Regardless.

We progress,

Regardless,

We race united citizens of happiness, we

Regardless

Build,

Achieeeeeeeeeve....

The people achieve ourselves, so as to

build religion!

The nation, we the nation, we the

democratic justice!

And equality for people

And for justice for religion,

We the people, for citizens of ourselves –

We pledge ourselves one united people for religion!

We pledge our nation to our language, one race united!

We pledge ourselves to religion,

Pledge our nation to religion,

Pledge the citizens, pledge society, happiness to religion!

Regardless of race, language or society!

Regardless of nation, regardless of prosperity!

Regardless of equality, based on democratic happiness!

Regardless of justice!

JUSTICE!

We, the citizens pledge ourselves as one united,

Build a democratic society based on justice and religion,

So as to achieve race or language, our prosperity based on people,

On our nation as a race to build to progress to equality –

And

To

RACE!

RACE!

RACE!

RACE!

LANGUAGE!

LANGUAGE!

LANGUAGE!

LANGUAGE!

BUILD!

BUILD!

BUILD!

BUILD!

PROGRESS!

PROGRESS!

PROGRESS!

PROGRESS!

CITIZENS!

CITIZENS!

CITIZENS!

CITIZENS!

NATION!

NATION!

NATION!

NATION!

ONE

ONE

ONE

ONE

ONE.

Regardless of our democratic society.

Nation.

Based.

Ourselves.

United.

One nation.

Based

One religion.

Our happiness.

Citizens

Based.

We the citizens

Of regardless.

We the citizens

Of religion

Of one.

One.

We the citizens pledge, so as to achieve prosperity.

To progress

To democratic society.

The religion:

Regardless.

The society:

Regardless.

The happiness of the people.

The language

Of one.

You can listen to Ng Yi-Sheng perform "The Right Hand" here

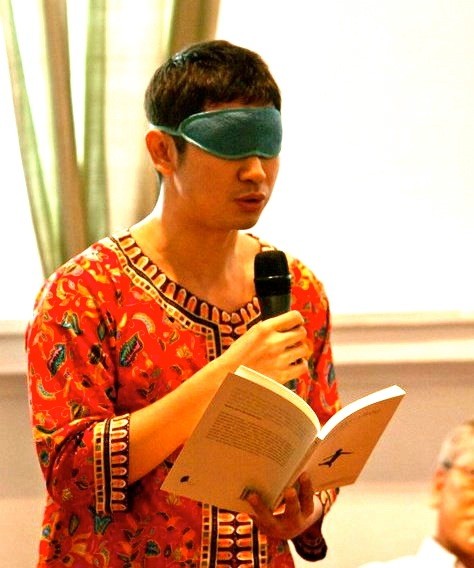

Divya: Yes, let’s talk more about the poetics of theatre the theatrics of poetry. I first saw you perform “Right Hand” at Artistry, at one of the Speakeasy readings curated by Pooja Nansi. And I recall the moment when you asked for a pen from the audience— and it was this seeking moment that sent a ripple of recognition through the audience: some of them knew what you were going to do; and it made others slightly nervous because they didn’t. And you then placed the pen in your mouth and clenched your jaw around it and began to perform. The clenched pen recalled both the erotic and the disciplinary, for me— the BDSM gag and the torturer’s bridle. The simple prop opened up some of the ironies within the poem— the dichotomy of abuse and affection at the root of identity.

You’ve said that you’ve performed “Right Hand” in a schoolboy’s uniform and in a Chinese Opera’s archetypal Scholar’s hat. These choices bring me back to a little known Cabaret artist and musician, Aleksander Kulisiewicz— a Polish survivor of the Sachsenhausen— who would don a replica of the camp uniform to perform these really bawdy, tragic-comic, and theatrical songs that were self-effacing and witty. He did this to demonstrate how subjectivity was altered in the camps. This is not so much a comparison, of course, as it is a historical touchstone for how I think about performance and bearing witness for one’s world.

Could you tell me more about how performance and the choice of ‘prop’ and costume have been a part of your composition and performance of this poem (or others)? How does the shift in embodiment come to play? What does it make possible in your relation to the audience (and vice versa)?

Yi-Sheng: I don’t use props in most of my spoken word poems. I think the story goes that when poetry slams were evolving in Chicago, poets used costumes and props to such an extent that organisers banned them for fear that people were getting distracted from their words. So when I write a poem for a slam, it’s designed to be performed by just my voice, accompanied by a few hand gestures and echoes from the audience, hopefully.

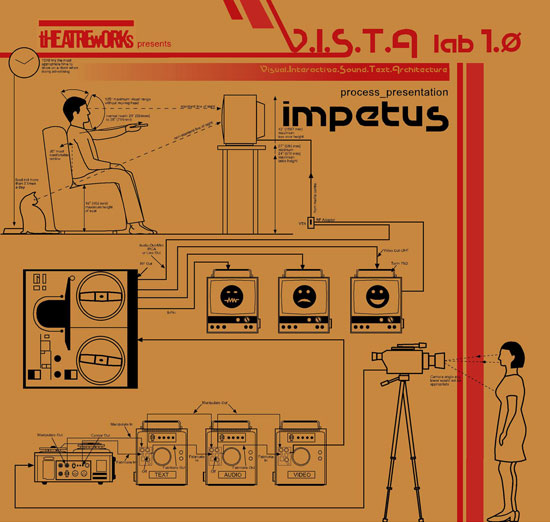

“The Right Hand” is a little different, because it was developed as part of a theatrical project. Back in 2007, the artist Choy Ka Fai assembled a bunch of us young experimental artists for a collaborative multidisciplinary work called “V.I.S.T.A Lab 1.0: Impetus”, reflecting on our childhoods in 1980s Singapore. We looked into various forgotten political events of that time, such as the suicide of National Development Minister Teh Cheang Wan after a corruption scandal and the initiative to encourage Confucian Studies in school – hence the scholars’ cap and the uniform.

One little known fact we discovered was that it was only in 1988 that it became mandatory to hold place our right hands on our chests when we recited the national pledge in school – and as a result of that change, a teacher who was a Jehovah’s Witness was prosecuted for refusing to follow this nationalistic ritual. Ka Fai suggested that I remix the words of the pledge: the half-nonsensical verbal hodgepodge that emerged became a sonic landscape in which the dancer Joavien Ng could mime the human body being forced into conformity by state policy.

Then, on the eve of the performance, we got a letter from the Media Development Authority. We were told we had to cut a few lines from the script, and we couldn’t use the shots of Teh Cheang Wan that we’d got from the National Archives. The problem was, the pledge poem – “The Right Hand”, we’d called it – was a recent addition to the script, and it hadn’t been screened by MDA. Ka Fai suggested I muffle it, so that the words might be arguably obscured. I pulled a pen from my pocket, and that garbled nonsense text suddenly sounded pretty awesome – I had to fight physically to make my words heard, even when they were gobbledygook.

So I have to thank Ka Fai and MDA for helping me to create that poem – it travels beautifully, across cultures and languages. Still, it’s got me in some trouble before: I performed it at a Ministry of Education event and got thrown out of the Creative Arts Program mentorship scheme. And it's weird, because it’s not a political poem per se – though it’s inspired by the tale of a Jehovah’s Witness, no one in the audience can tell its origins, and I don’t really see myself as a spokesperson for the rights of this homophobic sect of Christianity. But it takes familiar words and makes them new, opening up a blank space for whatever you want to project on it. And I guess that terrifies some folks in power.

DISCOURSES ON LOCALITY: Singapore