'How much can a famished being dream?'

Ethos Books and poetry publishing in Singapore

During my years in Singapore, I found myself in cafés and libraries reading anthologies and monographs marked with a stark, elegant icon. A swatch of black fabric fanned open? A pie with a dark slice carved out? A stylized ginko leaf floating in white space? A clock paused at five to eight? The books that I kept encountering at poetry readings, in my students’ hands, and on my friends’ coffee tables had this emblem as well. It was the icon of Ethos Books. As I leave the island-nation for Michigan, I wrap Discourses on Locality with this closing interview with Ethos Books, a singular publisher of poetry in Singapore.

Ethos was founded in 1997, by Chan Wai Han and Fong Hoe Fang. The press’s ten-person team enjoys a keen balance between clearly distinguished roles and collaborative practice, and its vision, expertise, and efforts have opened new avenues for young, genre-bending poets who have pushed forward an emerging Singaporean poetics. I’ve spent time with the editors in their compact office, stacked from floor to ceiling with shrink-wrapped, perfectly bound books. We talked aesthetics, publishing logistics, and the delicate politics of funding sources for truly independent poetry publishing in Singapore. Here, I record a conversation with members of the Ethos team: Ng Kah Gay and Kum Suning, Ethos’s editors; Fong Hoe Fang, its cofounder (along with partner and cofounder Chan Wai Han), Foo Peying, and Jennifer Kuan.

Divya Victor: I’m so glad to be talking with the Ethos Books team today. I have a lot of questions, but let’s start at the very beginning: When the press was started, was there a specific absence or lack you were setting out to address in Singaporean literature?

Ng Kah Gay: Singapore culture in the 1980s felt paper-thin, ever ready to give up its ghost. Behind the façade, there was a black hole, driven by political will, which was actively siphoning off the will to imagine. These were days when censorship pre-empted articulation. The term “OB markers” (Out-of-Bound markers) occurred with frequency in mainstream press.

Fong Hoe Fang: Yes, carrying on from what KG says above, that feeling was very pervasive. When we decided to start the press, there was nothing specific in our minds except an overwhelming belief that we had to have alternative voices which would help reflect the ethos of our times more spontaneously and more accurately.

Divya: Why poetry, then, to “reflect the ethos of our times”, as you say? What was the motivation for the initial foray particularly into poetry? And what was the very first poetry you published?

Hoe Fang: In a way, you could say that it was poetry which selected us. Two very young men had approached us to publish their collections of poetry. We were delighted by and astonished at the quality of their writing and the thoughts they articulated. We thought: this is good enough to start a small press; we will use poetry as our main vehicle to push back against that literary cultural desert encroaching upon modern Singapore. [N.B. These “very young men” would go on to become very illustrious writers: Alvin Pang (Testing the Silence) and Aaron Lee (A Visitation of Sunlight).]

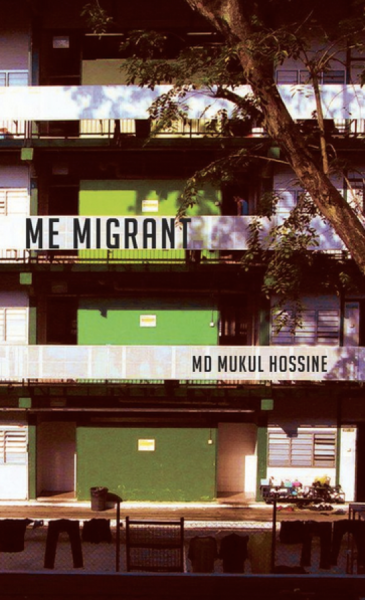

Housing Development Board flats seen through Royal Poinciana's branches (Syafiq Rafid).

Housing Development Board flats seen through Royal Poinciana's branches (Syafiq Rafid).

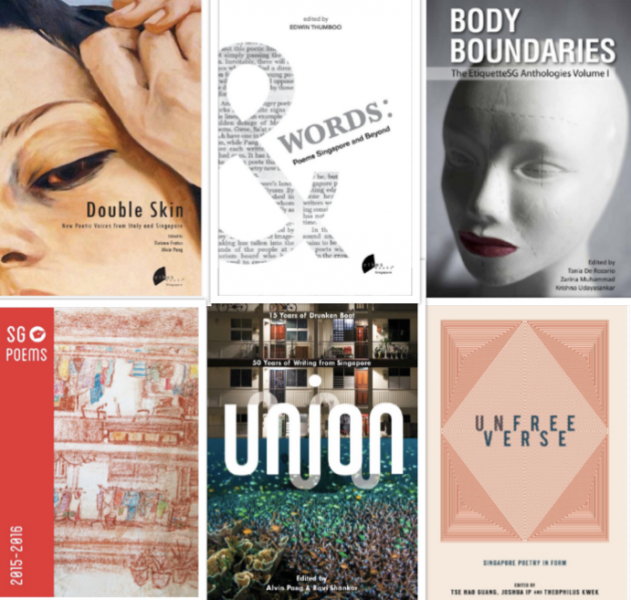

Divya: I love the image of the cultural desert encroaching on this otherwise lush, fecund geography. The press’s reach, its own geographic spreading, has been remarkable — Ethos has published writers from the United States, Italy, Portugal, the Philippines, and so on. How do you imagine the “reach” of the press?

Kah Gay: In shape, I imagine Ethos Books as a raintree, rooted in and drawing from Singapore soil, but with its leaves aspiring towards the great beyond that transcends familiar boundaries. Mr. Fong is currently hatching a publishing project to support displaced refugees.

Hoe Fang: Books are an important part of historical memory. Well-written books will live for centuries and reach across the ages. That’s why the purported first emperor of China burned books. He sought to rewrite historical narrative to reset society to his world view.

Divya: Would you say that local literature is your first priority, or might there be a diasporic, transnational thrust that you’re curating as well?

Kah Gay: We have been receiving manuscripts from writers based in other parts of the world. Somehow, it feels like it is in our DNA to unearth and work with writers from our region, such as Myanmar and Thailand.

Foo Peiying: We look to scripts that align with our values and make sense to be published in Singapore. Someone could be scratching their heads when they first encounter Children of Las Vegas by Timothy O’Grady or Blood: Collected Stories by Noelle Q de Jesus in our catalogue but themes like human vices and migration are relevant to this island-state.

Divya: Who are the Singaporean authors/poets who have had international appeal? What kind of work does the press do to curate this movement of identities?

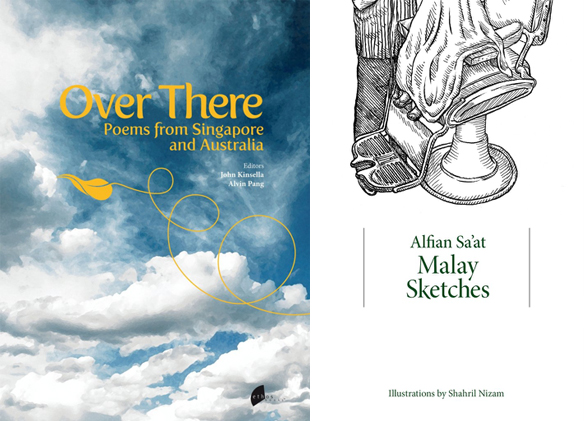

Hoe Fang: Poets like Alfian Sa’at, Alvin Pang, Theophilus Kwek, Yeng Pway Ngon (in Chinese) have proven to have international appeal. We continue to bring their books as well as their physical selves to book fairs or literary conferences, and recommend them for literary festivals.

Kah Gay: And we’re also working with our women authors and poets, so their books become better known internationally.

Kum Suning: Alfian Sa’at’s works are possibly the most-travelled in our stable of writers. He’s a multi-hyphenate, being a playwright, poet, and prose writer too (you know I was going for alliteration). He’s been translated into German, Swedish, his plays have been staged in London, Zurich, Berlin … and his texts are studied in universities overseas. His works are mediums for discussing matters close to his heart — home, identity, culture. And his voice is critical, sometimes self-deprecating, and very real. Alvin Pang is another outstanding poet, who’s been translated into over twenty languages, and has two full poetry collections published in Croatia and the UK. He continually pushes, and crosses boundaries, paving new roads so that others can go on further. And I think that’s very generous — a spirit that Ethos holds dear.

We’re grassroots people, and we have a strong interest first and foremost in the Southeast Asian region, so hopefully, in the near future, we’ll see enriching collaborations that’ll expose the international audience to the very rich literatures here. But also, I’m thinking of the question and that it seems more natural that Ethos not “curate” such movement of identities. But perhaps we encourage our writers in whichever artistic and geographic direction they so choose to pursue. Like the analogy Kah Gay has used — a raintree whose roots are firmly Singaporean, but with limbs far-reaching, sheltering.

Divya: I’ve relished locally published literature these past three years and have marvelled at the titles being released every year by the nation’s most significant presses, which for me include Math Paper Press, Epigram, and Ethos. How does Ethos distinguish itself from the goals and aesthetics of other presses in the nation?

Kah Gay: When Peiying came up with her vision for marketing our titles, she called for each campaign to have “an actionable plan.” Ethos I know is a publishing house whose aesthetics is founded on “理念” (li nian), which translates both as “philosophy” and “an active principle of being.” I hope that we will continue aiming for an aesthetics that embodies aspiration and action.

Peiying: We find it more important to put the writer and their work out there over our brand. We prefer to remain in the shadows and do what we can to make the book shine. This is why we value working closely with our writers for their opinions from the editorial process to book production and marketing. That does present its own set of dilemmas when everything in the world seems to be pointing to the need for strong branding in a saturated market. But perhaps it’s enough for the book to stand out on it’s own? I do think we also have a soft spot for stories on the making and breaking of the human spirit.

Suning: Ethos is about people. When I first joined Ethos and was shown around the place by Wai Han (Mr Fong’s wife), she talked to me about the flowers in the garden, whether I preferred teh or kopi, whether it was tough to find my way here, and about the beautiful rainbow refraction that appears on the floor tiles when the sun hits the window at a particular angle, at a particular time of the day. And we still talk about these after all this time. So when asked how we differentiate ourselves from the goals and aesthetics of other presses, anywhere, I think the difference lies in how we treat our people. And consequently, how we treat their work. We try to be fair to all. We try for the best. It’s inconvenient, it’s idealistic, it doesn’t make money. But there it is: a better way to live.

Divya: I appreciate that story about Wai Han! I too see this in the press’s approach. I recall meeting with you about American micropress cultures many months ago — we talked about Les Figues, Make Now Books, Insert Blanc, Ugly Ducking Presse, and so on. At this lunch meeting, I was struck by how much the team cared about whether I was getting enough to eat, whether there were enough greens and tofu on my plate. The effort was interpersonal — how might this play out in your editorial and design philosophy?

Suning: Our mission has always been to give voice to emerging, exciting voices from diverse backgrounds. So when we realise it’s a new name sending brilliant stuff our way, our mouths gape a little. (We anonymise before reading submissions, by the way!) Once we accept a manuscript, we are committed to it fully as we want to ensure that we prepare the best possible runway for the writer’s take-off. We’re invested in nurturing the writer’s voice (preserving the integrity of their voice, prodding, poking, and even pushing them sometimes, but always holding their hand), the production of their title, and what this particular publication means for them in the larger scheme of things. We (try to) look out for their futures, and essentially do assess manuscripts based on these three qualities: fresh, different, enduring (which happens to be our tagline).

Hoe Fang: We are usually very light-handed in our edits for books that we really like and promote. When we start from that place of liking a manuscript, we want to give as much freedom as we possibly can to the writer. Where we like the ideas, but are not too happy with the craft, we will have a heart-to-heart chat with the writer to see if they are willing to re-write with some guidance. If not, we will drop the manuscript.

Divya: How would you describe the poetry/poets that the press has chosen to showcase, support, and publish over the last few years?

Kah Gay: Writing can be untamed, wild, or purring like a domesticated creature. We ask ourselves “Are we fully encountering the spirit of each manuscript?” Criteria exercised thoughtlessly and routinely can become limitations.

Peiying: The Ethos values of choosing works which are fresh, different, and enduring still stay true today, and it’s something we often reference when we evaluate a manuscript. I do think our aesthetic is shifting slightly — but that comes with our growth in learning more about the world and knowing how far we can push with Ethos.

Suning: New teams, different inclinations, different specialities and focuses will surely influence the approach we take, but so far our guiding principles have anchored us the same.

What are the aesthetic parameters that fascinate the press? What do you reject and roll your eyes at?

Kah Gay: I think we continually confuse ourselves: on occasion, coherence between form and content. But we are equally fascinated by fracture.

Suning: We love films and music, and art, and popiah. We love meeting creatives on chance encounters and seeing how the stars align. We roll our eyes at ignorance. I can actually hear Jennifer (our resident feminist schooling us better since 2016) in my mind.

Peiying: ... And we reject insensitivity.

Jennifer Kuan: When a character is reduced to a cultural or gendered stereotype, or gets appropriated as a convenient plot device rather than as a well-realised character, I do get quite incensed. I believe a valuable and important manuscript should counter such assumptions, instead of feeding them.

Divya: So, what would you say is the press’s duty to the poet?

Kah Gay: To listen and to become attuned to the poet’s idiosyncrasies, and to be savvy to connect his/her poetry to willing ears.

Peiying: To try to convey the beauty of their words to ears of the world rushing by.

Kah Gay: Not sure. How deep is their act of reading? I am not sure if we wish to intrude into their personal habits, but it would be brilliant if they could experience and inhabit the imaginarium created by the web of language.

Peiying: Poetry, for most part, dwells in a very personal sphere, and the people who do pick up poetry in Singapore are very much endeared to it. This endearment doesn’t necessarily translate to Singaporean poetry though. We’ve met and had conversations with people who just couldn’t understand and don’t want to spend time with Singaporean poetry when they’ve loved Robert Frost or William Wordsworth.

Suning: Raised in a society drilled to be pragmatic, poetry has little tangible, transference value to consumers. But readers … they are our baes.

Divya: And what seems to draw your baes — your readers — repel them, excite them? What might we learn through their patterns?

Kah Gay: They seem drawn to the larger values: beauty, truth, goodness, the possibility of these, and their converse. But also to little things, marginal existences, and curios. Readers are curious, and their curiosity goes into, beyond, and around light, entering unseen pockets. Our curation must be as bounteous and diverse as possible.

Suning: For all the dissing Lang Leav gets, we should also remember that it resonates with many who memorise her lines by heart, for themselves. I think if you publish for yourself only, that’s not it too, isn’t it?

Divya: That’s true — and the too-narrow view could sometimes make us amnesiacs. So let’s try a wider one — could you describe what you see as the present state of Singaporean poetry?

Kah Gay: To be honest, I think Singapore poetry and writing is currently bridled. There’s a story by Kurt Vonnegut, “Harrison Bergeron”: Singaporean writers have had to do a Harrison Bergeron — think Alfian Sa’at and Cyril Wong — they’ve been labelled and killed off in the eyes of the mainstream as “enfant terrible,” and there will be more deaths (messianic or little deaths) before our collective consciousness can break away from the shackles of the prevailing matrix.

Peiying: Formal poetry and spoken-word poetry is underrepresented in print.

Suning: Works in English are exploding, but not so much the other languages. Tamil and Malay especially.

Hoe Fang: There has been an influx of writers attempting to publish poetry, and pretty good support from both the writing community as well as the National Arts Council. This obviously has resulted in exceptional talent surfacing, and we hope that they will continue to write and not go the way of so many other good poets in the past — into the commercial market. Free verse seems to be the favourite form now, but I do wish that some poets will find new meaning in using the old forms of metre and rhythm, and that more will explore subjects that are marginalized.

Divya: Certainly — and it is also important to think about how a press explores marginal mediums. Might alternate mediums like digital publishing, cross-listed platforms like sound-media/online publishing and so on become necessary in the upcoming years?

Suning: Recently we adapted a story from an anthology of anti-realist fiction, this is how you walk on the moon, into a promenade + forum theatre performance that was staged at the ArtScience museum. It was about taking stories places beyond the printed page, and the event saw a really good turnout, with many attendees who have heard of neither our press, nor the fact that edgy works like these are being written and published on this island. We definitely need allies beyond the industry, and many of our projects have leaped off and branched out like fractals. We are very open to new adaptations!

Peiying: Necessity is a state of mind — it’s more important to do what we think is right, for both the publishing house and the world. If we value printed books, and think the world should still be able to hold a book in their hands, we have to do it. If we value putting things online for accessibility by our friends halfway around the world, we will do it.

Hoe Fang: Alternate and new mediums which allow writing to cross genres and artistic forms are rising, and the young writers are growing more experimental in how they want their writing to be articulated. This bodes well in the call for creativity, but we also need to sit back once in a while and ask “creativity for what?”

Divya: I appreciate this question, Hoe Fang — “creativity for what?”, indeed. Of course Ethos has published some very compelling political anthologies and tracts, and the catalogue is much more vast than the genre we’re discussing. In Ethos’s diverse genre history, how do you imagine the press’s contribution to intellectual, political, artistic life in Singapore outside of publishing?

Suning: We want to reflect the spirit of a people, and capture the ethos of our changing times. We want to publish the marginalised, contribute to the plurality of views. Even if we disagree among ourselves, we deliberate very hard if publishing something under the Ethos imprint will accomplish that. Publishing books is a responsibility because we are spreading ideas. And sometimes, we forget. To quote our writer, Leonora Liow, “Ignorance can be a weapon when skilfully wielded. Fashion anything into a weapon, and it will serve you.”

Divya: What can publishers be doing to transform these spheres (the political, the artistic) in Singapore? What are some of the challenges you face when undertaking this larger effort?

Hoe Fang: A press needs to grow from mere publishing and print production to meaningful engagement with its readers and the community. Book readings, book clubs and book discussions should be a regular diet of publishers. It may take some time, but if one keeps at it, the spheres you refer to will change.

Kah Gay: Radical transformation involves creation and destruction. Transformation can also happen over an infinitesimal number of steps. Publishers, collectively, need to publish works that create possibilities and destroy falsehoods, and sustain their enterprise over glacial time to shape the multiverses of perceptions and understandings.

Peiying: Books are just one course in the magic feast. I want our books to do what food does: surprise, inspire and comfort a soul in need.

Suning: It’s a constant struggle against an audience that wasn’t raised on the arts and humanities. So even the arts get sucked into the commercial mentality out of circumstance. We’re constantly trying to achieve a balance between viability and sanctity. …

Divya: Singapore’s publishing is built on a bedrock of governmental funding and subsidy — but this bedrock can also become splintered into a cave — shutting in creative expression and freedoms. What do you want to see happen in Singaporean poetics/poetry that isn’t happening now? How might governmental funding forces like the National Arts Council assist with or contradict/thwart that desire?

Kah Gay: How much can a famished being dream? Writers and publishers need to incarnate themselves into bodies that can be sustained by current levels of nourishment.

Hoe Fang: If we are looking for real creativity and giving support to our writers, the National Arts Council should not be subsumed to the dictates of government. Art as a form is somewhat different from other areas of society. You need a bit of recklessness and freedom for genius to evolve. But NAC faces a far bigger obstacle than most writers envisage. It’s not as simple as “No censorship” or “No governmental controls.” Few governments in the world would like to make funds freely available to all and sundry, especially when the work mocks them sometimes. Yet, most recognise that that is what makes for creativity sometimes. It’s like a cake of wet soap. How firm should your grasp be? Too hard, and the soap slips. Too soft, and the soap slips as well. So NAC is trying to calibrate that grasp, when some other model should be looked at? Perhaps don’t use a cake of soap? Use liquid soap.

DISCOURSES ON LOCALITY: Singapore