When the school board was asked to read Wallace Stevens

'They shall know well the heavenly fellowship … '

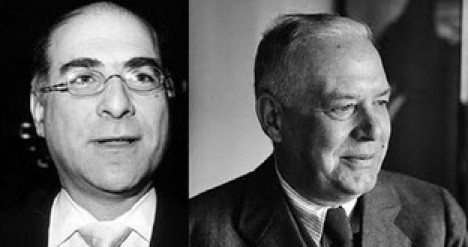

Harold Levy was an interim chancellor of New York City's public school system at the end of Giuliani and the beginning of Bloomberg. Levy got his BA from Cornell at a time when people like Allan Bloom (The Closing of the American Mind) and poet A. R. Ammons held forth — and Harold Bloom, too, for that matter (I think). Levy hung out in an intellectually vibrant circle that produced (not surprisingly, when you think of A. Bloom's potential influence) Paul Wolfowitz and other neo-conservatives. (Wolfowitz had grown up partly in Ithaca; his father was a professor of statistical theory at Cornell.) Somewhere along the line — from Ammons and maybe Harold Bloom — Harold Levy picked up an absolute love of Wallace Stevens. And, many years later, when he was appointed chancellor he told all the members of the New York City School Board that they would be convened to discuss three poems by Stevens (Levy now recalls that two of these were “The Emperor of Ice Cream” and “Sunday Morning”) and would be given a violin lesson by Isaac Stern. Levy's role (he was a businessperson) was to bring efficiency to the system, but he also brought what might be deemd the opposite — a conviction that Board members should be conversant in the philosophical questions of the sort that one would hope kids in the schools would face if and when presented with probing teaching. On May 2, 2000, the New York Times covered this story and here's the whole article:

May 2, 2000

Schools Chief Plays Higgins To Unlikely Eliza, the Board

By ABBY GOODNOUGH

A few weeks ago, the seven members of the New York City Board of Education found something odd in their mailboxes: three Wallace Stevens poems, courtesy of Harold O. Levy, the interim schools chancellor. ''Poetry,'' he wrote in an attached memo, ''can give voice to the inner souls of people who lead seemingly mundane lives.

Then came the news that Mr. Levy was planning a series of lectures, intended specifically for the enlightenment of the board members. The first, scheduled for tomorrow night, will be on cosmology. That is, the study of the universe.

And next week, Mr. Levy will gather the school system's 43 superintendents for a group violin lesson at Carnegie Hall, taught by none other than Isaac Stern. What is going on here?

If the school system's top officials did not have enough to worry about, with Mr. Levy pushing them to be more efficient and accountable, now he wants them to think more, too. Music and poetry are among the more esoteric parts of his plan to raise the level of debate on education policy, he says. That means focusing less on administrative minutiae, and adding intellectual rigor to the often tedious board meetings.

''The notion is to change the areas of conversation,'' Mr. Levy said in an interview, ''so that we are squarely confronting some of the great philosophical questions of our day.''

To that end, Mr. Levy has enlisted his friend, Jonathan Levi -- a novelist, jazz violinist and founding editor of the literary journal Granta -- to be the resident intellectual at 110 Livingston Street.

Mr. Levy, whose official title is executive assistant to the chancellor, says that his duties include bringing board members, school officials and students ''into the secret society that is New York City's intellectual culture.''

Whether they will go willingly is another question. After all, the members of the Board of Education -- who are appointed by the mayor and the borough presidents -- are known more for their political allegiances than their intellectual pursuits. At least one has suggested that Mr. Levy stick to being a manager and let them choose their own enrichment activities. ''For the most part I'm ignoring it,'' said Ninfa Segarra, one of Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani's appointees to the board, referring to the clippings that Mr. Levy has been circulating from Scientific American, The New York Review of Books and other erudite journals. ''I guess he thinks we don't read on our own. But every single board member gets Education Week. Most of us are pretty well versed on the issues.''

Ms. Segarra said she had not decided whether to attend the lectures. And as for the poems, she said she had not received them. ''Probably if I had gotten it I would have thrown it out,'' she said. ''I'm not a poetry kind of person. I like serial killer novels.'' Other board members appeared appreciative, or at least tolerant, of what one wryly described as Mr. Levy's attempt to play Henry Higgins.

''There is a very fine line between sharing information and being viewed as arrogant,'' said William C. Thompson Jr., the board president. ''But I don't think Harold has fallen on the side of arrogant. I see this as Harold constantly thinking and sharing ideas he finds exciting.''

Jerry Cammarata, one of the three board members who fought Mr. Levy's appointment, said his attempt to spark intellectual discourse was appropriate because the board's primary responsibility should be to debate and create policies. ''I think 110 Livingston should be an intellectually enriching experience for anyone who walks through the doors,'' Mr. Cammarata said. ''We should be continually thirsting for information. If he thinks this stuff is relevant, it would be imprudent and disrespectful of us not to give it a shot.''

But whatever their reaction to Mr. Levy's recent efforts, the board members pointed out that they had been mulling ideas long before Mr. Levy's appointment in January.

''We're always swapping stuff around,'' said Terri Thomson, the Queens member. ''The more we can learn together, the better.''

So far, Ms. Thomson and five other board members have signed up to attend the cosmology lecture, at the Museum of Natural History. The speaker will be Neil deGrasse Tyson, the director of the Hayden Planetarium, who will provide insights on how to teach such a complex subject. In addition to board members and administrators, Mr. Levy has invited several dozen of the city's science teachers. For the second lecture, Alan Brinkley, a history professor at Columbia, will discuss the civil rights movement.

''This is a chance for them to exercise their minds,'' Mr. Levi (his name is pronounced with a long i), the son of a philosophy professor at Columbia, said this week. ''We want them to be doing mental push-ups.''

For the district superintendents, Mr. Levy has already brought in speakers like Jonathan Kozol, who has written extensively on urban education, and Kati Haycock, director of the Education Trust, a Washington-based advocacy group for poor and minority students. And, of course, they have the violin lesson to look forward to.

Mr. Levy said he and his boss would not be foisting lectures and clippings on the board -- and violin lessons on the superintendents -- if they did not believe that their audience was already highly intelligent. ''Henry Higgins was assuming that his audience was unsophisticated,'' Mr. Levi said. ''We're assuming our audience is sophisticated enough to listen to lectures at the highest level, but that in the course of their normal days as educators, they don't get the opportunity.''

But Ms. Segarra pointed out that Mr. Levy, a Citigroup executive, was hired for his corporate expertise, not his intellectual vigor. She said he had not used his managerial skills as much as she had hoped, and that he should be focusing on the coming summer school program, which is to be the largest in the city's history. ''He has a very limited amount of time to do some very critical things,'' Ms. Segarra said.

But while the plan to create a literary salon of sorts at 110 Livingston Street might not seem to fit in with Mr. Levy's efforts to make the Board of Education more businesslike, Mr. Levi said that in fact, the two efforts fit together seamlessly.'

'To run a business you need to find the best resources and apply them as efficiently as you can,'' he said. ''My job is to look at the issue of resources more broadly, in terms of the artistic and intellectual resources of New York City.'' Mr. Levy did not deride his predecessors, but said that, as career educators, most were focused on a handful of initiatives directly related to classroom instruction. Many of those initiatives were abandoned when the next chancellor came in, he said.

''I don't want to blow through here with an initiative or project that won't withstand the test of time,'' Mr. Levy said. ''What I want to do is have a public debate about the methodologies and what the true needs of the system are.''

But whether such a debate will lead to permanent change is as open a question as whether Mr. Levy will become the permanent chancellor after his temporary contract ends in July. Quite possibly, his friend Mr. Levi said, people are reacting enthusiastically to Mr. Levy's initiatives simply because they do not expect him to stick around. ''The chancellor's office is such a revolving door,'' he said, ''you never know whether people are genuinely interested or just nodding politely and waiting for you to depart.''