What is poetry?

A response to a request for 500 words on this small topic

Someone at my university who edits and publishes a newsletter asked me if I would write 500 words on what makes poetry distinctive. I balked at such a task, but then decided to produce the statement. For better or worse, here it is.

***

Whenever poetry becomes a topic movingly discussed by many people for whom it is not a daily — indeed, not even a monthly — thing, I realize once again what draws me to it ever and always. In a poem, how you say what you say is as important as, sometimes more important than, what you say. Is that a radical view? After all, content is central to communicating. But what about times when communication has broken down? If Allen Ginsberg in writing and performing “Howl” did not in the poem itself emit such a howl — if he did not himself evince the “mad” non-conformity he saw in the best minds of his generation — we would no more remember his poem today than we do the many smart and interesting books of sociological nonfiction written during the 1950s about the supposedly disaffected (but actually hyper-affective) postwar generation. PennSound (the archive of recordings of poets, the largest in the world) includes the riveting performance Ginsberg gave before a huge, engaged, at times ecstatic audience in Chicago in 1959. How Ginsberg says “Howl” is as important as what he says, for sure. Words about crying out can themselves cry out.

So that is poetry. A form of saying. Not so much the things being said. I really don’t mind the cliché that understandably irks many of my colleagues in the field of poetry and poetics: when someone gives a powerful, memorable speech — when a speaker uses parallelism or seems to have cared about the rhythm of the sentences — we say “it has poetry.” I don’t mind such obvious praise, because it once again puts poetry at the center of what causes us to listen, to really hear, to attend. A poem can help us comprehend our role as its respondent.

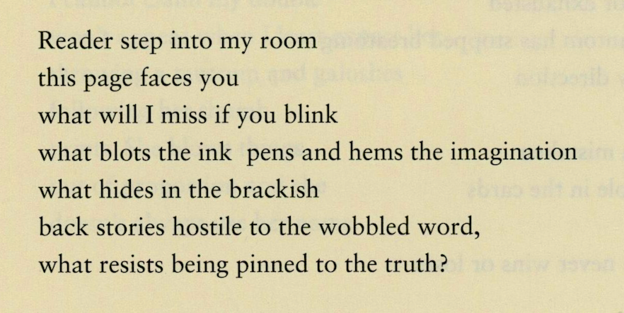

The great poet Erica Hunt is a Kelly Writers House Fellow during the spring of 2021. Whenever I read — or, better, hear recited — her poem “Reader we were meant to meet,” I think about how and why I cannot help but listen, cannot turn away from hearing, must attend. Because the poet is not just talking to me, but about me — about why I am necessary “even in the failure to communicate.” Poems I admire require my involvement in the project of “toppl[ing] distinctions” between who gets to talk and who is being asked to listen. And that and only that kind of engagement — the convergence of writer and reader, of speech-maker and audience, of the talker and the silent, of the poet as subject and the reader normally supposed to be an object — will “ease doubt.” In a poem more about our role than about hers, Hunt is saying that solutions to the problems plaguing us require the confluence of “I” and “you” that the poem both promises and models. “Reader,” Hunt requests of us, “step into my room,” and then needs us to attend: “What will I miss if you blink.” Poetry is that which encourages us to open our eyes and stay focused. And then the poet is only there if we are too.