Voice of the poet programmer Jörg Piringer

For most of us, our first act in life is a speech act. We are born, we inhale, and then some of us sneeze, but most of us scream. For the next few months we make sounds, which we’re repeatedly told are letters. Somehow a song called The Alphabet gets stuck in our head. We can’t stop humming it. Eventually someone hands us a pen.

Viennese poet, programmer, performer, musician, composer, lecturer and researcher Jörg Piringer works operate in the moments human voice, machine language and letter forms meet.

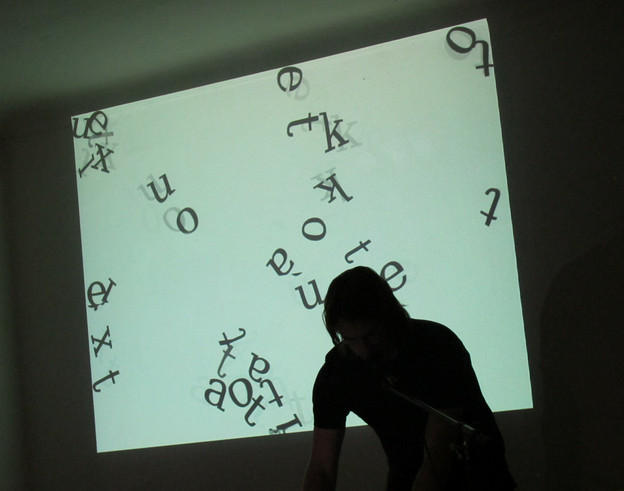

Piringer uses his voice as an interface and as a medium. In his electronic visual sound poetry performance frikativ, Piringer generates visual sound poetry in real-time by speaking and vocalizing into a microphone. Fricatives are audible frictions, consonant sounds produced by forcing breath through a narrow, constricted, or partially obstructed channel. In frikativ, the channel of the vocal tract is appended to that of the microphone, which is further extended by cables to a computer wherein live and pre-recorded voice sounds are modified through signal processors and samplers. Piringer’s custom software then analyzes these sounds to create animated abstract visual text-compositions.

Through a long, ongoing, iterative, and intrinsically performative writing process, Piringer has created a massive custom-written computer program with which he builds his performance works. Similar to the way one game engine can be used to create a wide range of different games, Piringer can now drawn on his own code base to create new behavioural logic sets for each new performance.

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz expands the visualization process employed in frikativ to create a much more complex and reactive system. The voice is an input signal, mapped directly onto the output that the audience sees and hears. Algorithms taken from physics, biology and mathematics are assigned to individual letterforms, endowing them with specific behaviours. Some text and sound particles drop to the floor, some move left to right, some act as if they are insects, some makes sounds when they collide, others are destroyed. The autonomous movements and behaviours of these visual elements on the screen cause new sounds to be produced, thus creating an audiovisual feedback loop which Piringer has called “an autopoetic live performance system.”

As anyone who has ever attempted to listen to a poetry reading in a café bar knows, it's quite hard to analyze the sound of a voice reliably in a performance environment. In frikativ and abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz, in addition to the voice input, key presses are also required to set the sampling process in motion. A key press attaches a sampled sound to a specific letter.

Voice-only interface remains Piringer’s aspiration. Why go to these great lengths? Why not just push buttons? Piringer pushes programming languages instead. His ever-expanding custom-written code base makes it possible for him to speak more and more directly to the computer, demanding the computer engage with him as a performance partner rather than a mere calculation machine. The computer hears sounds, which, it is repeatedly told, are letters. In its cooperative moments, the computer becomes a digital extension of the voice of the poet programmer. Together they perform audiovisual compositions, generate unforeseeable abstractions, and improvise poetic potentialities. Like all speech acts, even as they are uttered, they are always already vanishing.

Voice-only interface remains Piringer’s aspiration. Why go to these great lengths? Why not just push buttons? Piringer pushes programming languages instead. His ever-expanding custom-written code base makes it possible for him to speak more and more directly to the computer, demanding the computer engage with him as a performance partner rather than a mere calculation machine. The computer hears sounds, which, it is repeatedly told, are letters. In its cooperative moments, the computer becomes a digital extension of the voice of the poet programmer. Together they perform audiovisual compositions, generate unforeseeable abstractions, and improvise poetic potentialities. Like all speech acts, even as they are uttered, they are always already vanishing.

abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz is a work in progress. It has been performed in countless contexts around the world. Each instantiation reveals a multitude of new possibilities. In 2010 Piringer created an abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz iPhone/iPad app, which has since won an number of awards. The app invites the audience to share in the sheer delight of setting abstract audiovisual poetry in motion. abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz is available for download from the iTunes store.

Performing digital texts in European contexts