Collecting digital literature in Europe

Digital Literature. It’s out there, I swear. The question is where? The answer is everywhere. Over the past twenty years or so, a diverse international community comprising a combination of independent and institutionally affiliated authors, academics, researchers, critics, curators, editors and non-profit organizations, has produced a wide range of print books, print and online journals, online and gallery exhibitions, conferences, festivals, live performance events, online and DVD collections, databases, directories and other such listings of creative and critical works in the field.

Collecting is key to the promotion and preservation of any genre. Collecting digital literature is a complex undertaking. Authors are dispersed, works are disparate, and platforms are unstable. The task of bringing together works as divergent as Donna Leishman’s ultra-graphic audio-visual Flash re-“writing” of the RedRidinghood fairy tale and Netwurker MEZ’s entirely textual code-work _cross.ova.ing ][4rm.blog.2.log][_ written in MEZ’s own digital-creole "mezangelle", to cite two examples from the Electronic Literature Collections Volume One and Volume Two respectively, is made all the more unwieldy by the as yet amorphous definitions of what it electronic literature is and what it is not. And there remains, the pesky problem of the name. How what and why do we call this thing we do?

The Electronic Literature Organization was founded in Chicago in 1999, to “foster and promote the reading, writing, teaching, and understanding of literature as it develops and persists in a changing digital environment.” The collecting, codifying and conference-making initiatives of the Electronic Literature Organization have helped coalesce a divergent set of practices into "a name, a concept, even a brand," as Lori Emerson noted in a recent blog post on "e-literature as a field."

In his paper “Weapons Of The Deconstructive Masses: Whatever the Electronic in Electronic Literature may or may not mean,” presented at the 2009 Electronic Literature Organization conference Visionary Landscapes, and since published in Hyperrhiz.06, John Cayley argues against the term ‘electronic literature,’ advocating instead for ‘writing in networked and programmable media.’ In her 2008 book, Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary, N. Katherine Hayles makes a critical distinction between ‘literature’ and ‘the literary,’ pointing to the later as having a much broader conceptual framework, within which certain literary hybrids may bridge physical and digital modes of creation and dissemination through a process Hayles terms intermediation. In his 2011 book, Digital Art and Meaning: Reading Kinetic Poetry, Text Machines, Mapping Art, and Interactive Installations, Roberto Simanowski favours the term digital literature because it “seems to offer the least occasion for misunderstandings. It does not refer to concrete individual characteristics such as interactivity, networking, or nonsequentiality as do terms such as interactive literature, Net literature, or hypertext, which are better qualified to describe genres of digital literature. Instead, it designates a certain technology, something the term electronic would not guarantee, given the existence of other arguably electronic media such as cinema, radio, or television.”

Whatever the kids are calling it these days, hypertextual hypermedia experimental electronic digital interactive immersive multi-modal multi-media inter-media hybrid literary art is being created and collected in an increasingly wide variety of contexts.

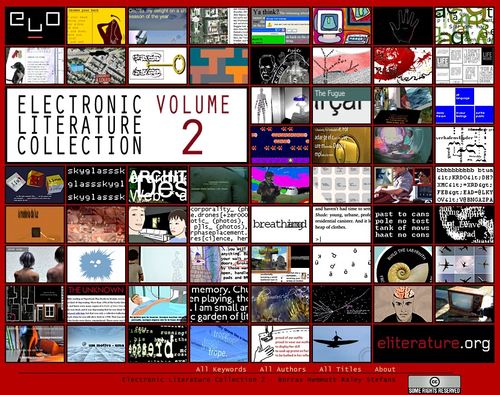

The Electronic Literature Organization, now hosted at MIT, recently re-launched the Electronic Literature Directory and published its long-awaited Electronic Literature Collection Volume Two, which contains work from countries as diverse as Austria, Australia, Catalonia, Canada, Colombia, France, Germany, Israel, The Netherlands, Portugal, Peru, Spain, UK, and USA in a wide range of languages including Catalan, Dutch, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish Flash, Processing, Java, JavaScript, Inform, HTML, and C++.

[pictured above: Electronic Literature Collection Volume Two, 2011]

The NT2 research lab at the University of Quebec at Montreal hosts the Répertoire des arts et littératures hypermédiatiques which contains 3500 entries, with a special emphasis on works in the French language. New works in French and in French translation are featured in NT2’s online journal bleuOrange.

The complexities of collecting digital literature in general are complicated tenfold by the myriad of countries cultures and languages operating in close proximity in the European context, each with wildly divergent art histories, digital infrastructures and social realities. To date, most initiatives have been university-based.

The University Fernando Pessoa, Oporto, Portugal hosts PO.EX’70-80 – Digital Archive of Portuguese Experimental Literature.

[pictured above: Rui Torres, Poemas no meio do caminho, included in the Electronic Literature Collection Volume Two and in the ELMCIP Knowledge Base]

Hermeneia Research Group based at the Universitat de Barcelona features an online anthology comprising more than 700 digital literary works of dynamic poetry, hypertextual narrative, hypertext essay, cyberdrama and generated literature. This anthology is also a clear of example of the myriad of literary works in different languages that emerge each day in the digital environment.

Electronic Literature as a Model of Creativity and Innovation in Practice (ELMCIP), a collaborative research project funded by Humanities in the European Research Area (HERA), involves seven European academic research partners and one non-academic partner in England, Finland, Netherlands, Norway, Scotland, Slovenia, and Sweden.

Of particular interest to European practitioners of electronic literature, ELMCIP has created a Knowledge Base, which provides cross-referenced, contextualized information about authors, creative works, critical writing, and practices. This Knowledge Base is populated by the active participation of a community of international researchers and writers working on electronic literature. For more information on how to contribute to the Knowledge Base, please visit: http://elmcip.net/knowledgebase

ELMCIP has also put out a call for submissions of electronic literature from European writers and practitioners for an upcoming ELMCIP Anthology of Electronic Literature. The submission deadline is 7 November 2011.

European authors are also encouraged to submit up to four works per year to European eLiterature Collection.

Performing digital texts in European contexts