Visionary architecture, 1960

'Social usage determines what is visionary.'

I'm fascinated by the “Visionary Architecture” show put on at MoMA in the fall of 1960. The exhibit consisted of materials (photographs of models, plans, drawings) from 28 ideas for cities and urban structures “considered too revolutionary to build.” “Ideal projects,” writes the show's curator Arthur Drexler, “afford the sole occasions when [the architect] can rebuild the world as he knows it ought to be.” And: “When ideal projects are inspired by criticism of the existing structure of society, as well as by the architect’s longing for a private world of his own, they may bring forth ideas that make history.” Theory and practice — vision and realism — merge in this presentation. “Today virtually nothing an architect can think of is technically impossible to realize.” Here, then, comes a definition: “Social usage, which includes economics, determines what is visionary and what is not.”

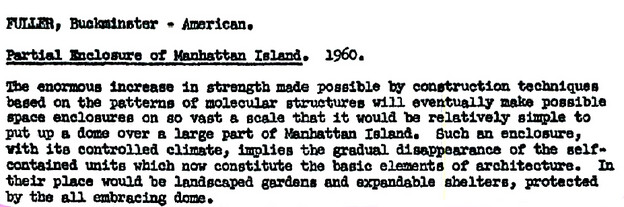

Buckminster Fuller's project on display here was brand new — done in 1960, just before the show opened. The wall label from the MoMA exhibit is reproduced above. This is vintage dome-obsessed Fuller, but now with a hint of ambient-coverage aesthetic the manner that would emerge with Christo and others. A dome over “a large part” of Manhattan.

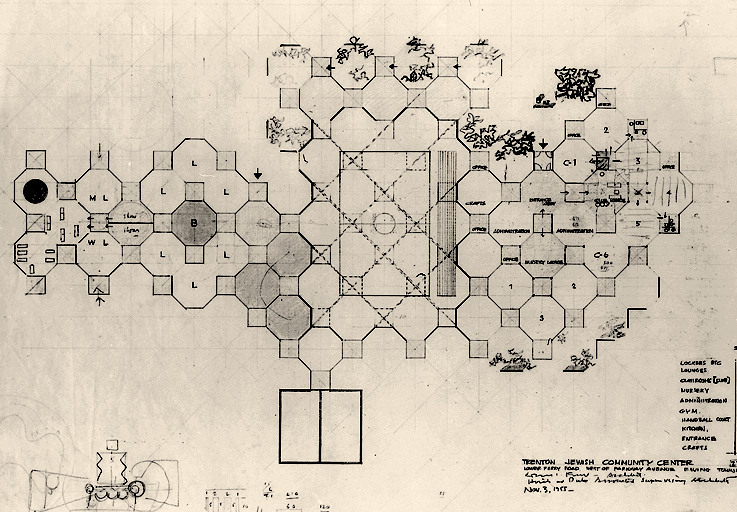

The Louis Kahn represented here was Kahn at his most unbuildable: “Center City,” plans completed in 1957. (The “Center City” referred to is Kahn's Philadelphia. The chances that the Main Line fathers of planning in that city would build a Kahn around Philly's baroque City Hall were nil. One wonders what Drexler means by "social usage" in that instance.) Kahn's radical idea is that “a street wants to be a building.”

The Louis Kahn represented here was Kahn at his most unbuildable: “Center City,” plans completed in 1957. (The “Center City” referred to is Kahn's Philadelphia. The chances that the Main Line fathers of planning in that city would build a Kahn around Philly's baroque City Hall were nil. One wonders what Drexler means by "social usage" in that instance.) Kahn's radical idea is that “a street wants to be a building.”

William Katavolos is here also. His “Chemical Architecture” (also dated 1960) implies the claim that chemistry had advanced far enough so that powdered or liquid materials which, “when suitably treated with certain activating agents,” expand to great size and then become rigid. New City: just add water. Read and observed today, these materials truly seem a conceptual poetics. In the architect's descriptions of the project, he has assumed the existence of such materials, and has indicated “the growth forms they might take.”

Frederick Kiesler's “Endless House” (1949-60) is here too, the city as a “twisting, continuously curved ribbon wrapped around itself.”