Ngā Kaituhi Wāhine Māori — Māori Women Writers

Kia ora tātou katoa. [Let us all be well.]

He mihi tino mahana ki a katoa hoki. [A warm greeting to all also.]

Ko he korero tēnei mo ngā kaituhi wāhine Māori kei konei: ngā wāhine tino mōhio me ki te timata o te tuhi te taima katoa. Te tuhi o ngā mōteatea, ngā waiata, ngā ruri, ngā whiti te mea te mea te mea. [This is a commentary about Māori women writers: very intelligent women always at the creation of writing. Writing song-poetry, songs, love poems, verse and so on.]

Ka huri ahau ki te reo Ingarahi ināianei mo ngā tangata i kāore mohio taku reo tuatahi. [I will now turn to the English language for the people who don't know my first language.]

Māori women, then, are often the inaugrators, the initiators of poetry. Here it is stressed yet again that for Māori everything is connected holistically, that it is all rather arbitrary to sub-divide songs as separate from poetry and so on, that such are pākehā striates only. Therefore, Māori women writers cross such so-called boundaries and always write holistically. The paragraph directly below here was not included in my Landfall piece ‘on’ Ngā Mōteatea, as alluded to in the first Jacket 2 commentary post, for reasons of space, but I here reinclude it, to more appositely show what I am saying here.

“As regards patere, kaiorarora, oriori, waiata tangi and waiata aroha, ‘the majority of the composers are women’ (Ngata), whilst the composers ‘of the ceremonial songs of the tohungas [sic] are usually men’ (ibid.) The patere in particular were marked by abusive language, a rapid tempo and eye-rolling, hand-quivering and swaying! Women were really fighting back against idle gossip, jealousies, bullshit.”

“Although somewhat of another simplification into arbitrary ‘categories,’ this is a very significant point, I believe. Māori women had historically a major role in not only the composition of Māori poetry, but also its performance: they composed as they were the most affected by battle loss and the subsequent anxious awaiting the return of the man, love loss and the desertion of the man, (death and betrayal), curses and insults from other women. Tuini Ngawai (Ngāti Porou — as were Ngata and Dewes) was just one such important modern writer of ngā mōteatea Māori, and a collection of her work was produced in 1985.”

“Women composers tended to show how they felt personally about an event … the chiefly men tend to employ more exaggerated comparisons than the women … It is perhaps in the composition of laments that differences between female and male composers tend to be most pronounced … There seems to be no doubt that the main composers of love songs are women” (Mead, 1969).

“Mead makes a further important point that the composers of ngā mōteatea Māori were generally high-born women or (male) chiefs, who advanced the social values of high birth, chieftainship, primogeniture via their compositions.”

I then also went on to name some historically earlier composer-poets such as Te Puea Herangi, Arapera Blank, Ngoi Pewhairangi, Maewa Kaihau, Erihapeti Murchie; all creating ngā mōteatea raua ko ngā whiti hoki [both song-poems and poetry also.] I stress also here, that sometimes their work was solely in the English language, sometimes completely in te reo Māori; at other times a compote of both. All were staunch women, who never did receive the recognition due them from not only their male peers, but also the New Zealand public, press or literary crowd. Being a Māori woman in Aotearoa-New Zealand society is and remains never ‘easy’ and necessitates strength, drive, initiative. (I know from personal experience, believe me!) Kia kaha, kia toa, kia manawanui [Be strong, be brave, be of stout heart] personifies such an approach.

Now, I also made specific mention of JC Sturm aka Jacqui Papuni in that first commentary post — everything folds back cyclically, as we approach the end of this series, ripeness is all, after all, eh — yet there were also other harbinger Māori women poets, writing in the English language, who gained less recognition than her and who in fact went overseas to become published. They are Vernice Wineera and Evelyn Patuawa-Nathan, whose books I have had myself for quite some time and the covers of which are depicted below. I make mention again, that ki te ao Māori, everything is interconnected, therefore singers and musicians such as Mahinārangi Tocker, Moana Maree Maniapoto, Emma Paki et al, are for me, ngā kaituhi wāhine Māori, are poets also, while Patricia Grace, Keri Hulme, Bub Bridger and Kāterina Mataira, as just four of several others, must also be mentioned here.

Now, I also made specific mention of JC Sturm aka Jacqui Papuni in that first commentary post — everything folds back cyclically, as we approach the end of this series, ripeness is all, after all, eh — yet there were also other harbinger Māori women poets, writing in the English language, who gained less recognition than her and who in fact went overseas to become published. They are Vernice Wineera and Evelyn Patuawa-Nathan, whose books I have had myself for quite some time and the covers of which are depicted below. I make mention again, that ki te ao Māori, everything is interconnected, therefore singers and musicians such as Mahinārangi Tocker, Moana Maree Maniapoto, Emma Paki et al, are for me, ngā kaituhi wāhine Māori, are poets also, while Patricia Grace, Keri Hulme, Bub Bridger and Kāterina Mataira, as just four of several others, must also be mentioned here.

Before we continue by asking several contemporary Māori women poets their own opinions about what it is like writing in a somewhat constrained Aotearoa poetry scene, I will share a couple of resources. Firstly there is the stalwart and in many ways pioneering work of Alice Te Punga Sommerville and her seminal Once Were Pacific. Michael O’Leary also has written extensively regards Māori women writers in his recent Ph.D studies, while his mate, Mark Pirie, has published Broadsheets specifically dedicated to artists like Mahinārangi Tocker (issue #10.) Finally, Vaughan Rapatahana wrote Maori Poetry in English, a two part article published in English in Aotearoa, a couple of years ago.

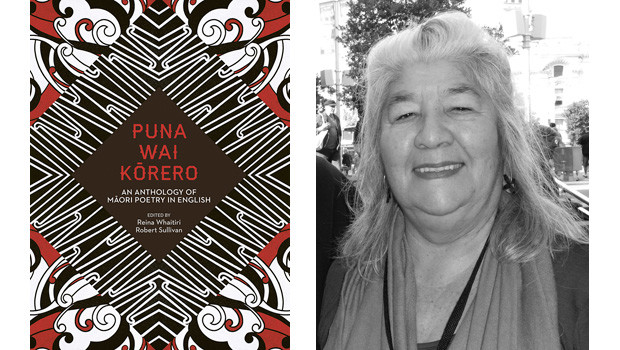

And of course we must place in the forefront, the compilation Puna Wai Korero, edited by Reina Whaitiri (see below) and Robert Sullivan and published in 2014, more on which shortly.

Another significant piece of writing is that of Powhiri Wharemarama Rika-Heke, who insists Māori writers all, grab the English language by its throat and write back to the centre via their own english — code switch, utilise te reo Māori, incorporate the topos and stylizations of mōteatea. Her staunch 1996 chapter Margin or Centre? “Let me tell you! In the land of my ancestors I am the Centre”: Indigenous writing in Aotearoa is very well worth checking out; while Hirini Melbourne, of course, went even further and insisted Māori write in their own language first and foremost … but, perhaps I am tangenting a bit, eh.

Reina Whaitiri, of course, was one of the editors of Puna Wai Korero and she answered some of my enquiries regarding what it is to be a Māori writer in New Zealand — “I am Māori so my perspective can be nothing but Māori, as well as Pākehā, but mainly Māori. I don’t consider a Pakeha perspective normal, it is just the majority. I always have a Māori hat on when I write and I always see the world through a Māori lens. I do employ te reo when I feel it is required and when my limited knowledge is up to it. Some concepts can only be expressed in te reo however. If and when Māori poets are included in Pākehā anthologies they are not usually given the respect and acknowledgement they deserve, which is why Robert Sullivan and I decided to put a totally Māori anthology together. Puna Wai Korero is edited and written entirely by Māori. It is a very different anthology from others offered in Aotearoa and probably will not be acknowledged as being ‘poetry.’ However, I think it’s a great collection and gives a Māori POV [point of view] on the world, politics, society, and everything.” [My, Rapatahana, highlights here.]

Reina Whaitiri, of course, was one of the editors of Puna Wai Korero and she answered some of my enquiries regarding what it is to be a Māori writer in New Zealand — “I am Māori so my perspective can be nothing but Māori, as well as Pākehā, but mainly Māori. I don’t consider a Pakeha perspective normal, it is just the majority. I always have a Māori hat on when I write and I always see the world through a Māori lens. I do employ te reo when I feel it is required and when my limited knowledge is up to it. Some concepts can only be expressed in te reo however. If and when Māori poets are included in Pākehā anthologies they are not usually given the respect and acknowledgement they deserve, which is why Robert Sullivan and I decided to put a totally Māori anthology together. Puna Wai Korero is edited and written entirely by Māori. It is a very different anthology from others offered in Aotearoa and probably will not be acknowledged as being ‘poetry.’ However, I think it’s a great collection and gives a Māori POV [point of view] on the world, politics, society, and everything.” [My, Rapatahana, highlights here.]

Hinewirangi (Kohu Morgan) is an especially powerful poet and I have been a fan of hers for years, from Broken Chant as depicted above and published by Tauranga Moana Press and Robert de Roo — whom I well remember, through to her more recent poems, as below. Hinewirangi speaks — “I don’t define myself or label myself a poet, I don’t fall into that Pākehā need to put us into category. But that I am Hinewirangi with a story to tell about myself and the impact of colonization on Māori people. I have something to say, and I want to say in the way I express, so no not a poet, others may call me that and that’s okay.” Her whakataukī is especially relevant — “Kāore te kumara e kōrero ana me tona reka / the kumara doesn’t speak of its own sweetness.”

Hinewirangi (Kohu Morgan) is an especially powerful poet and I have been a fan of hers for years, from Broken Chant as depicted above and published by Tauranga Moana Press and Robert de Roo — whom I well remember, through to her more recent poems, as below. Hinewirangi speaks — “I don’t define myself or label myself a poet, I don’t fall into that Pākehā need to put us into category. But that I am Hinewirangi with a story to tell about myself and the impact of colonization on Māori people. I have something to say, and I want to say in the way I express, so no not a poet, others may call me that and that’s okay.” Her whakataukī is especially relevant — “Kāore te kumara e kōrero ana me tona reka / the kumara doesn’t speak of its own sweetness.”

“Yes I do deliberately concentrate on Māori take [issues] using metaphoric language, it is the language of our tipuna [ancestors], I travel in between te reo pihikete and te reo rangatira. Yes I would love to see more poetry around Māori issues. I think the thing that drives me in my work is that there are 4.5 million people that occupy Aotearoa, of that 4.5 million Māori are fifteen percent and of that fifteen percent sixty percent are incarcerated. I have much to say about that kind of take.” Below are two poems typifying her determinedly strong attitude —

|

[Here is a piece that challenges men in Whaikōrero.] I see you Māori man, upon the marae of our tipuna, pontificating your own self importance. forgetting that I too have arrived on this marae with my ancestor you quoting your own whakapapa. regurgitating whakatauaki after whakatauakī to show what your intelligence yet you expect me to sing your song? Hinewirangi |

[Here is another piece] Brother I hear you, reverence in your heart, yet the strength of our tipuna seep through the blood of your veins, recognizing me, my tipuna connecting your whakapapa helping me to stand strong at your side. Brother I will sing your Mōteatea with joy.

Hinewirangi |

Kiri Piahana-Wong, has, of course, been highlighted several times during these commentary posts — primarily as she is so v ersatile. She is also most definitely a Māori woman writer and mover-shaper of note. “I don’t consciously use te reo in my poetry, but it does find its way in there. I think it depends on the subject matter of the poem. Sometimes a Māori word is the only right word. I think I feel the influence of my Māori ancestry in my interest in writing poems about seen and unseen worlds, and the line between the two. In this mysterious place I feel the presence of my tipuna.” Kiri is at right.

ersatile. She is also most definitely a Māori woman writer and mover-shaper of note. “I don’t consciously use te reo in my poetry, but it does find its way in there. I think it depends on the subject matter of the poem. Sometimes a Māori word is the only right word. I think I feel the influence of my Māori ancestry in my interest in writing poems about seen and unseen worlds, and the line between the two. In this mysterious place I feel the presence of my tipuna.” Kiri is at right.

Marino Blank is the daughter of an important kaituhi wāhine Māori, Arapera Blank, whose own compilation of poems, For Someone I Love, has only just been released, after all these years. Marino tells us, “I define my poetic voice as Māori modernist. It’s not a conscious choice. The visual pictures the words evoke define themselves in the process of writing. The imagery I draw from come from the richness of the New Zealand landscape, the connection to Māori ‘lore’ the definition of family. The different perspectives ‘Māori to Pākehā’ is best observed in [a] cultures’ distinct approach to death and the process of grieving. When my mother was dying I lay beside her and talked. We touched, she woke. My family filled the room. My mother died in the arms of her tribe. My father Swiss, died on his own, alone just as his sister did. Quietly exiting on his own terms, as he wanted too. My mother’s family are and were eloquent. When they spoke the used the ‘ha,’ the breath, the power of pause. The stylistic devices that I employ exploit the same rhythm and timing. It is inheren tly Māori. I do not speak the reo, I do use the kupu [words] I know because the translation to English doesn’t fit.”

tly Māori. I do not speak the reo, I do use the kupu [words] I know because the translation to English doesn’t fit.”

“I would like to see more Māori poets published. The scope to get published is tiny. My brother Anton [Blank] publishes a Maori literary journal Oranui which show cases the scope of Māori talent out there. We need more … a comfortable space in which we can perform our words.” Marino’s own new set of poems, entitled Crimson, has also just been published. Marino is pictured at right, with two of her poems further on.

Marewa Glover is right up front, right from the get-go. Tino ka mau te pai!, “He wahine Māori ahau. He kaituhituhi ahau. No reira, he Māori kaituhituhi au. I’m a Māori woman. I’m a poet. Therefore, I am a Māori poet. What I see, sense, dream, and vision is interpreted from this, my perspective, kneaded, carved, fired, and polished by everything that I could have been, everything that has happened to me, everyone who has loved or hurt me, and everything that I witness. We Māori are unique, and I am very aware of this as my heritage — that we are relatively new into the contemporary world. Our umbilical cord to pre-European-industrial life has not been completely severed, though the jagged mussell shell of colonisation clumsily gouges away at the abilities and insights only ‘exotic’ Indigenous tribes of recent exposure, like ours, can bring to the infintile world. Without deliberate effort to focus, my view is kaleidoscopic and multi-layered. There is too much happening everywhere in the past, present, and future and across time all at once. There are too many people, too many feelings, too many problems. Poetry is like a jeweller’s loupe pinpointing one tiny defect in humanity at a time or enabling the discovery of perfection. Poetry is a kind of peace. Everything is normal, Māori — everything can be viewed and interpreted from a Māori perspective.”

“I balk at being packaged up, tied with black, red, and white ribbon like a gift to be given and refused or shelved. I’ll write about anything if there is fraud afoot, if there is some rhetorical trick to mislead, some violence on another. And that’s Māori. That’s one way I have and continue to survive the unrelenting racism, sexism, and compulsory heterosexuality of the dominant Pākehā culture that means to eliminate us completely. We are already redundant to them, they think, as they stamp out their genuine Māori souveniers in Taiwan. Our language, our tikanga, matauranga, our genes, our waiata, our food and ways of cooking, our art, our plants, our rongoā, our whānaungatanga, our wairua — our culture is unique and we must strive to learn and to reinstitute and to live being Māori, as much as each of us can within the contemporary context we are in, given the ways in which each of us are abused on a daily basis. Thus, yes, I try to incorporate te reo Māori. Anyway, sometimes only a Māori word can truly convey the meaning intended. Sometimes I have woven words, carved words down the page, emulating other Māori languages. And my words can end up in painting or song.”

Marewa continues, “The Aotearoa literary scene appears to suffer a colonial-complex: it fears it’s written off as a small, forgotten backwater. The once-lauded tales of natives in grass skirts doing the haka on pink and white terraces have lost their readership back in the mother country. There is hunger to recapture lost fame, a desparation to discover the next Keri Hulme, Hone Tuwhare or Janet Frame, who will titillate the international readership and win awards. Most Māori writers suffer like impoverished French impressionists of the 1700–1800s scrambling to produce and exhibit their work in the Salon de Paris or put off from even trying. Only a select few are picked to receive support, promotion, and publication. There is a lack of infrastructural support to nurture Māori talent, a lack of publishing opportunities and a disheartening wall of backs turned to and gushing over the latest light.” [My, Rapatahana, highlights.] Marewa is pictured above and one of her staunch poems is below right.

|

Mother Mum I find myself in verse It happened when you gifted Hand on cheek You breathed life from One life force to another What a gift It has transcended The mountains of Gabris and Hikurangi It speaks from intuitive moments The thread form one step to another A pattern of the kohunga of learning Which leads to heaven and beyond

Father’s Day Auckland 2015 Twenty one years ago you Became a father Today we celebrate With a turn table and a record Collection forty years in the making The transition from lover to father Provider to the golden years of Golf and music appreciation has been Twenty five years of love and song Your gift the song in my heart Our daughter laughter in my soul Marino Blank(Notes

Gabris – Mountain in Switzerland

Hikurangi – Mountain of the Ngati Porou

Kohunga – school) |

Fear is … Fear is a father’s rage his eyes sharp as swords his words deafening blasts his hand a wrecking ball Fear is a suburban lounge room 3 machetes in the corner behind the TV not being able to see a way out him saying “take your panties off” Fear is the moment before blacking out hands closing tight around your neck the white light tipuna voices Fear is the black portal beckoning in the corner of the room your own brain urging you on to the train tracks beside your house Fear is gunfire, bombs, a burning house your child starving your baby choking sick the ground shaking a tornado ripping away all shelter Fear is not a weapon to be cloaked in terms “unsafe” “unhappy” “scared” to be used to manipulate gain to have someone at work sacked Fear minimized & used by Pākehā in the workplace against Māori this is not fear this is racism this is colonization. Marewa Glover |

Paula Morris is a leading Aotearoa-New Zealand writer per se, who has also spent a considerable amount of time overseas (where she was when this 2011 interview was made.)

Paula Morris is a leading Aotearoa-New Zealand writer per se, who has also spent a considerable amount of time overseas (where she was when this 2011 interview was made.)

I asked her if she equates herself as a specifically Māori writer, “Usually I get this question in a different form: do I define myself as a New Zealand writer? I was born in New Zealand, and my whakapapa [geneaology] is Māori and English, with occasional rumours of someone Portuguese; I’ve lived overseas for most of my adult life. Much about me reflects or reveals all of the above — my accent and idiom, my habits, my points of view, my physical and psychic and cultural inheritances. But I don’t define myself at all as a writer: that’s a job for critics, anthologists, and librarians. The question of what is a New Zealand writer and/or what is a Māori writer is an interesting and complex one, but I’m wary of the closing of doors, perhaps, and any notion of confines imposed by definitions. I used dozens of te reo Māori words in my novel Rangatira, and though I hoped most were clear in context, I suspect some were baffling to many readers … In my first novel, Queen of Beauty, I attempted a more Māori narrative structure, looking backwards and forwards to the past, and incorporated stories about Tawhaki and Tane, in part because it was a book about storytelling and myth-making.”

“My poems tend to be about places, like the new one, ‘St James Theatre, Auckland,’ that I recently finished [which is as below, by the way.] It looks back to a pre-European New Zealand, and further back to a pre-Māori one. I’m obsessed with the layers of the past, I suppose. I like the way the compression of a poem allows an intense engagement with one place, one moment, one investigation.”

Paula continues, “The poetry scene in New Zealand seems very vibrant and active to me, though I’ve only been home for less than a year. We do need a greater diversity in the voices that are getting published, which is why I’m increasingly involved in teaching community workshops, as well as young writers in schools. Our national literature doesn’t necessarily reflect all our perspectives and arguments and experiences yet. We all need to hear more voices, and encourage others to speak up.”

St James Theatre, AucklandSoon, towering above the old theatre, Beneath lie the ashes of an older theatre, Deep in the mud there’s a lumpy stretch Before anyone dreamed up a town, this was a gully Paula Morris

|

Me aro koe ki te hā o Hineahuone(Pay heed to the strength that is women) If Hinetitama can become Hinenuitepō crushing

the next man who tried to interfere with her between her thighs

Then I too can deal to any man who would enter me without my permission

If our tūpuna wāhine can have the courage and the vision

to leave their homes in search of new homelands

Then I too can leave any place that does not nourish and support me

If that great ancestress Wairaka can summon the strength of any man

and drag that great ancestral waka from the sea with her own bare hands

Then I shall not allow myself let alone anyone else

to think of me as less than his or her equal

This is what we mean when we speak of mana wāhine

It is the strength that is within us by virtue of our descent from Hineahuone

Which is why when you meet a woman you really ought to hongi

To pay heed To the strength That is wahine... Jacq Carter |

Jacqueline Carter has an interesting background, which she raises when I asked her about her identification as a Māori poet, ‘Yes, I'd define myself as a Māori poet in that I have, and therefore my poetry has, a perspective that is different from the usual (or mainstream) Pākehā New Zealand one… And this is despite my growing up Pākehā, in a Pākehā household, not knowing I was Māori (or also Māori, as well as Pākehā)… But that’s because I pretty much decided to learn te reo Māori as soon as I was told about it (meaning our whakapapa, 25 years ago)… Doing so led me into te ao Māori (the Māori world) and on a journey, which has often been (and simultaneously) exhilarating, sad, frustrating, terrifying, humiliating, joyful and awe-inspiring... I therefore feel I have come to see, to know, to feel and to experience the world in a way that differs from lots of people, and not just Pākehā, but Māori and non-Māori... I wasn't aware then of the whakataukī or proverbs that tell us that the language is the life force of the culture but I think it's been crucial to my journey ([and] needs to be learnt in conjunction with tikanga)... This doesn’t mean though that my perspective is also the same as that of other Māori… There are numerous differences between me and most Māori, especially those who "grew up Māori", or on their papakainga, or "connected" in some way... and between me and those who didn't…’ [My -Rapatahana -stress.]

She continues, ‘You'll note that I haven't called it "normal" though... To me it is actually entirely abnormal and becoming more so by the minute... I often stop and consider myself and the way that I live in the city especially; to me a crucial part of being Māori is to live in relationship with other people and the atua (meaning the gods) of the natural world that we are still living in, no matter how much we exploit and despoil it, or how removed we might feel in the city... I believe that such relationships are pretty crucial to being Māori... And yes we can say that the word itself (i.e. "māori") means "normal" or "ordinary" (as opposed to "supernatural") but I note that it also means "clear" and "intelligible," while māoriori means "free from anxiety" and "whakamāori" means "explain" or "elucidate." I also heard it defined a few years ago by the late kaumātua Kato Kauwhata (Ngāti Rangi, of Ngāpuhi Nui) as "mā" or "purity", "o" or "of" and "ri" as "vibration", so "purity of vibration"… And that's what I think it is all about; Māori people are supposed to relate to each other, the world around them and the worlds beyond this one through a purity of vibration...’

She continues, ‘You'll note that I haven't called it "normal" though... To me it is actually entirely abnormal and becoming more so by the minute... I often stop and consider myself and the way that I live in the city especially; to me a crucial part of being Māori is to live in relationship with other people and the atua (meaning the gods) of the natural world that we are still living in, no matter how much we exploit and despoil it, or how removed we might feel in the city... I believe that such relationships are pretty crucial to being Māori... And yes we can say that the word itself (i.e. "māori") means "normal" or "ordinary" (as opposed to "supernatural") but I note that it also means "clear" and "intelligible," while māoriori means "free from anxiety" and "whakamāori" means "explain" or "elucidate." I also heard it defined a few years ago by the late kaumātua Kato Kauwhata (Ngāti Rangi, of Ngāpuhi Nui) as "mā" or "purity", "o" or "of" and "ri" as "vibration", so "purity of vibration"… And that's what I think it is all about; Māori people are supposed to relate to each other, the world around them and the worlds beyond this one through a purity of vibration...’

Relatedly, then, Jacq Carter points out, ‘I don't deliberately concentrate on Māori themes, imagery, stylistic devices or use te reo Māori, but I think that if you look at my poems you’ll see that I do all of those things… I do it because it is what comes naturally, it is just what happens when I write them (…poems usually "happen" to me, they just come to me, and I am a conduit, helping to give them shape and form...I suppose it's a bit like weaving or carving, or even, if you think about it, having children…)’

When I asked about what she would like to see in the Aotearoa-New Zealand poetry scene(s) from her perspective as a Māori writer, she responded, ‘To be honest I'm not entirely sure that I'm enough in the world of "Aotearoa poetry" to comment or answer this question knowledgeably...I have to say too that my gut response to this is that of course there wouldn't be sufficient recognition, publishing scope or critical space given... I'm aware that poets such as Alice Te Punga Somerville have raised this question and I think it's a worthy one, which has made me consider much more critically whether or not it may be possible that I haven't had my own book published…because of the nature and content of my poems i.e. that they just don't resonate with a publisher (who isn't Māori) because they don't conform or adhere to their notions of literary excellence and literary merit and/or profess certain political viewpoints and/or are ultimately unintelligible (metaphorically, stylistically etc.) to a non-Māori publisher and non-Māori readership.’ Finally, Jacq Carter ended her intelligent reflections on this kaupapa, by adding, ‘I also have to say that it seems that our men have been far more successful than our women when it comes to penetrating the literary circles of non-Māori publishers and institutions…This has of course been good for all of us, and some of those men are among our heroes, but the poetic world of Aotearoa poetry is as much in need of the poetry of women as any of the other worlds known to any of us...’ Tika tau korero, e hoa [Your talk is right on, friend] - which is why also Jacqueline's poem as above resonates so much, drawing as it does so deeply on Māori history as well as mythology.

I do realise, of course, that several leading kaituhi wāhine Māori have not been included here. Reihana Robinson was indeed keen to contribute, but has serious whānau duties right now, whilst I have lost contact with Roma Potiki, unfortunately. Hinemoana Baker is currently resident in Berlin, while Amber Esau, of course, featured in an earlier post on Pasifika women poets … If I had room, I certainly would also have included Tracy Watson, Meri Marshall, and Tracey Tawhiao, among others . Aroha mai mo tēnei.

Suffice to say that Māori women writing poetry, in whatever language, in whatever format, are a vital creative current running profoundly through the terrain of Aotearoa-New Zealand literature. But — as expressed by all of them in this commentary — not only do they deserve far more recognition and support and kudos, they have earned it: they are living their kaupapa every single day without fail.

Mo te mutunga, he whakataukī [To finish, a saying]: Puraho māku, kei ngaure o mahi [Without effort, nothing happens.]

Kia ora mo te mahi o ngā kaituhi wāhine Māori.

Ngā whakaaro