A slowing 2: Gestures of attention

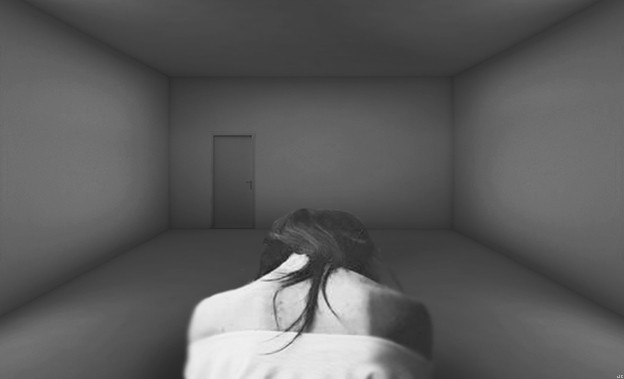

What can language open when given space? Poetry invites pause, the pause of music, of introspection, of spreading sensitivity. Maggie Nelson reports, in The Art of Cruelty, that John Cage proposed this “exceedingly difficult” advice: “The most, the best, we can do, we / believe (wanting to give evidence of / love), is to get out of the way, leave / space around whomever or whatever it is” (268). What is exceedingly difficult is necessary and important. So too with Cage’s more famous assertion that “there is not such thing as silence” (51). There is no such thing. It matters yet. It is still.

The notion of stillness – of residing, existing, in quiet happens ambiguously in being and also in-spite-of-it/still is/it is still/and/it is not (what might be such?). Baudrillard observed that “The Nothing does not cease to exist as soon as there is something. The Nothing continues (not) to exist just beneath the surface of things” (8). But it is precisely not nothing, the impossible silence, that asserts its being.

This is where art comes in.

Sontag calls silence “the artist’s ultimate otherworldly gesture; by silence he frees himself from servile bondage to the word, which appears as patron, client, audience, arbiter, and distributer of his work.” Silence—a freeing from bondage. To attempt to say what cannot be said is a kind of absurdity of arrogance in the face of rather fabulous impossibility. And yet, as Sontag noticed, “The exemplary modern artist’s choice of silence isn’t often carried to [the] point of final simplification, so that he becomes literally silent” (7). The words appear, radiant stillness. Attempting to “get out of the way” and show the way at once. Can we be bound and released in the same gesture?

The word is only one kind of bondage. In “The Glass Essay,” Anne Carson discerns that “Well there are many ways of being held prisoner” (7). That piece reveals for us many prisons: of the mind, of language, of family and lovers, of history, and most brutally of the soul.

Soul is the place,

Stretched like a surface of millstone grit between body and mind,

Where such necessity grinds itself out.

Soul is what I kept watch on all that night.

(Carson 12)

The soul is stretched in another in-betweeness here: watching what cannot be seen, it is of this speaker and apart from this speaker, mute and distant and impossibly part of the body and mind that knows it. Can we be bound and released in the same gesture?

Liberty means different things to different people.

(Carson 16)

Sontag tells us of the exemplary modern artist’s choice of silence, explaining, “More typically, he continues speaking, but in a manner his audience can’t hear. Most valuable art in our time has been experienced as a move into silence (or unintelligibility or invisibility or inaudibility); a dismantling of the artist’s competence, his responsible sense of vocation – and therefore as an aggression against them” (7). The aggression of the artist manifests in the demand of the audience to reach into the place that cannot be reached. Silence, the reticence of a poetics willing to leave space around its own most urgent concerns, becomes the violent gesture that might break open possibilities for understanding the bonds themselves.

It is a two-way traffic,

the language of the unsaid.

(Carson 21)

And Sontag understands this too: “Silence is a prophesy, one which the artist’s actions can be understood as attempting to fulfill and to reverse.” This prophesy can only work if the audience is intraactive, participating in the fulfillment and reversal, reaching toward that understanding. She continues, “As language always points to its own transcendence in silence, silence always points to its own transcendence – to a speech beyond silence.” As Carson writes of the “different things” liberty means (repeatedly) and the “many prisons” (over and over), spaces open up, as statements become reticence, the many and the different are not delineated, described, or represented. The gestures she writes are of attention. What could saying liberty do, if not constrain it into bondage?

Baudrillard, Jean. Impossible Exchange. trans. Chris Turner. New York: Verso, 2001.

Cage, John. Silence: Lectures and Writings. 1961. Hanover: Wesleyan University Press, 1973.

Carson, Anne. "The Glass Essay." Glass, Irony and God. New York: New Directions, 1995.

Nelson, Maggie. The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning. New York: Norton, 2011.

Sontag, Susan. "The Aesthetics of Silence." Styles of Radical Will. New York: Picador, 2002.

A slowing: Poetics and attention