Rodrigo Lira

Where the blood gets in /or/ Translating the last poet from Chile

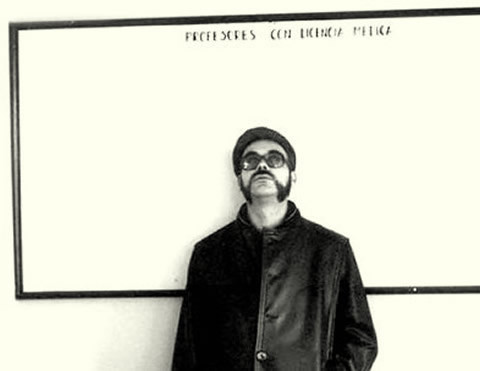

Rodrigo Lira was born in Santiago, in 1949. He studied philosophy, psychology, arts, communication arts, linguistics, and philology, among other things, but he never graduated. An eccentric fellow, he never published a book while he was alive. His poems, though, were spread by hand, around different university campuses, where he used to hang out with other poets and friends. Diagnosed with schizophrenia, Rodrigo committed suicide in 1981, on the day of his thirty-second birthday. Conisdered a cult figure, his fame most of the time prevents a serious assessment of the real importance of his work.

In 2010, the young translators Rodrigo Olavarría and Thomas Rothe received a grant from Chile’s Ministry of Culture to translate the poetry of Rodrigo Lira into English. The project, which includes over twenty poems of various lengths, is in its final stages of revision and currently seeking a US publishing house to print a bilingual edition. Thomas Rothe (Berkeley, California, 1985), who’s been living in Chile for almost ten years, generously accepted to respond to three questions about Lira’s work and biography, as well as the translation process. He holds an MA in Latin American and Chilean Literature from the Universidad de Santiago de Chile. He has translated poetry into both English and Spanish, including an anthology of contemporary US poets, La alteración del silencio (Cuneta, 2011), in collaboration with Galo Ghigliotto.

Can you describe briefly the myth of Rodrigo Lira? What’s the importance of his poetry? And what’s his place in Chilean literature?

Rodrigo Lira’s suicide on December 26, 1981, fostered much of the myth surrounding him as a poète maudit. And in fact his life reveals the reasons this label attached to him — a diagnosis of schizophrenia, social and literary marginality, as well as a taste for marijuana, more reminiscent of Beat poets than his Chilean contemporaries in the 1970s and early 80s. Having never published a book of poems while alive not only adds to the aura of a misunderstood poet, but also provides few records of critical attention with which to reconstruct the story of his life, a task that has been pursued mainly by gathering the personal accounts of friends, family, and fellow writers. These circumstances have also blurred the lines between myth and reality, which seems to have been Lira’s literary proposition.

Looking over the unclassifiable work Lira left behind, one thing becomes clear: his desire to enter the pantheon of Chilean literature was overcome by a desire to deface its engravings and cause laughter in doing so. And laughter introduced a new face into the somber drama so characteristic of national poetry up until the 1970s. Whereas many of Lira’s poems may resemble Nicanor Parra’s antipoetry or traces of the Chilean neo-avant-garde movement (Raúl Zurita, Juan Luis Martínez, Diamela Eltit, among others), Lira took parody and literary collages to such an extreme he often found no point of return or closure, marking a fine line between admiration and aversion for other, more established writers. He explored the limits and intensity of language in a way that also reflects and responds to the context of widespread censorship imposed by Augusto Pinochet’s seventeen-year dictatorship. Maybe that’s why Enrique Lihn, who himself maintained a somewhat turbulent friendship with Lira, considered his poetry unsettling, meant to keep us awake instead of dreaming.

Three years after Lira’s death, a group of friends compiled his manuscripts into what became his first book, Project of a Complete Works (Proyecto de obras completas), which has gone through several reprintings by different publishing houses. And in 2006, previously unpublished texts appeared in Sworn Declaration (Declaración jurada), expanding the interest in his work as well as the myth behind — or in front of — the poet. I would say that today, the enigmatic character Lira cultivated during a time of extreme silence and confusion continues to evoke ambiguity, intrigue, and laughter, though his name no longer occupies a marginal place in Chilean literature. I would also venture to say that the work of poets such as Lihn, Parra, Zurita, and Diego Maquieira, and certainly that of younger generations, cannot be fully understood without the presence of Lira’s persona and poetry.

Lira’s poetry is extremely colloquial and informal. Irony and intertextuality were important devices in his work. What challenges did you face when translating his poems?

One of the most striking traits of Lira’s writing is how much it draws from local references, whether urban markers in Santiago, the work of other writers and critics, or language. Chile’s unique geography as a long stretch of country locked between mountain range and sea has had a major influence in distinguishing the Chilean accent and dialect from other Spanish-speaking countries in Latin America. On top of that, Lira was born into an upper middle-class family, spent most of his life in Santiago, and belonged to the university scene, constantly interacting with young people, allowing him access to the argot of these geographic and sociocultural groups. And he exhausts that language, proving himself a master of local slang. This clearly posed a challenge for bringing many of his texts into English, and we had to accept the impossibility of “faithfully” translating many sections, which actually serves as a useful lesson for any translation. For the most part, words and phrases that refer to specific things often have to become more generalized and therefore lose part of their meaning, but at the same time broaden the interpretations. An example of this can be found in a poem where Lira describes festivities taking place during the “semana premechona,” literally the welcome week for first-year students at the University of Chile. To avoid obstructing the rhythm of the poem and tedious explanations, we thought it best that the setting simply be a freshmen week, allowing the reader to imagine such activities and celebrations at any university, whether they actually share similarities or not. Another example is in the title of the poem “4 tres cientos sesenta y cincos y un 366 de onces,” where, as you know, the last word in italics refers to the number eleven and also a traditional Chilean evening meal. In the English version we lose the double meaning, opting to express the importance of the number, which we believe refers to a specific date — September 11, 1973, the day of the military coup that ousted Salvador Allende. This sort of wordplay constantly appears throughout Lira’s poetry, and our renderings were made on a case-by-case basis but often accept the loss of certain nuances so present in the originals.

However, I don’t want to give the impression that we whitewashed these poems. Some are very dense, and we have intentionally kept them that way in their English versions. One of the most difficult tasks of translating poetry is not to fall back on the strategy of standardizing the language, making it overly readable or only concentrating on transmitting some sort of message from the poem. With that in mind, we have attempted to render these texts as accessible as possible to a broad readership while maintaining the intensity of language Lira developed as a trademark.

Other challenges included translating neologisms and rhymes, which in many cases we overcame with the help of dictionaries and thesauruses. One particular poem which merited almost constant dictionary referral was “Es Ti Pi,” or “Ess Tee Pee,” in English. The poem, often deemed “untranslatable,” consists of some five pages where each verse includes three words beginning with the letters S, T, and P, in that order. Attempting to follow the content of this brilliantly disturbing poem, English syntax clearly made it impossible to reproduce the narrative techniques used in the text. Again, this meant accepting the loss of nuances but, more than ever in this case, recreating a text in which Lira’s pen brings new possibilities to the English language.

Why do you think it is necessary to have his poetry available in English? What do you think the English-speaking reader will find in his work?

The most obvious objective is to extend the reach of this poetry beyond the linguistic borders of Spanish. Read in its historical and political context, Lira’s work expresses a response to the suffocating environment of the 70s and 80s in Chile, offering stories, sensations, and atmospheres that history books are unable to capture. We hope this poetry will help English speakers understand the complexity of recent Chilean history and, in general, that of the Southern Cone, where several other countries simultaneously experienced right-wing dictatorships. From a strictly literary perspective, Lira’s parodies of internationally recognized Chilean poets (Neruda, Mistral, De Rokha, Huidobro, and Parra) could complement perceptions of their work and its impact among Chilean writers of younger generations. Even Roberto Bolaño, who has experienced a boom among English-speaking readers over the last decade, wrote several pieces in praise of Lira, suggesting he could possibly be the last poet of Chile or Latin America — this is a very Bolañoesque exaggeration but displays his profound respect and admiration.

On the other hand, from a less utilitarian approach, the very process of translating Lira’s poetry into a different language and cultural context implies introducing new poetic forms into that language. This doesn’t mean Lira’s poetry will change the English language, but rather that the poetry assumes a new meaning capable of becoming a reference, miniscule as it may be, for poetry and literature written in English. Walter Benjamin believed translation allowed the original work to move into an afterlife, a different stage of existence with new possibilities. At the core of this idea, Benjamin is criticizing attempts to “faithfully” reproduce works of literature in different languages, defending the need for translation to change and renew the original. I like to think our renderings of Lira’s poetry head in this direction. I also tend to think Lira would have found it amusing to hear someone associate the idea of afterlife with his poetry, which he may have wanted to translate himself if he were still alive. Lira spoke English quite fluently and even wrote an untitled poem in English, which has not been included in any of his posthumous publications. It begins with these lines:

Being chased

as a hunting dog

persecuted by distant laughs

and cruel horns

I’m fixing a grave

where the blood gets in

ARS POÉTIQUE

for the imaginary gallery

Let verse be like a picklock

To break in and steal

The dictionary at night

With a flashlight whose beam is

deaf as an

Adobe wall

Wailing Wall

Licked

Hearing Walls!

a Rocket falls a Mirage flies by

the windows tremble

This is the century of neurosis and acronyms

and acronyms

it’s the nerves, the nerves

True vigor resides in the pockets

it’s the checkbook

Muscles are sold in packages through the Mail

ambition lingers

poetry doesn’t rest

it’s h

an

g

i

ng

in head offices at the Library Archives and Museums in luxury ass

ets of basic necessity,

oh, poets! Sing not

to the roses, oh, let them ripen and cook

rose bud jelly in the poem

____________________________________________________________________

The Author apoloJizes for having caused the Reader any trouble (Ur Spare Change = My Paychec)

ARS POÉTIQUE

para la galería imaginaria

Que el verso sea como una ganzúa

Para entrar a robar de noche

Al diccionario a la luz

De una linterna

sorda como

Tapia

Muro de los Lamentos

Lamidos

Paredes de Oído!

cae un Rocket pasa un Mirage

los ventanales quedaron temblando

Estamos en el siglo de las neuras y las siglas

y las siglas

son los nervios, son los nervios

El vigor verdadero reside en el bolsillo

es la chequera

El músculo se vende en paquetes por Correos

la ambición

no descansa la poesía

está c

ol

g

an

do

en la dirección de Bibliotecas Archivos y Museos en Artí

culos de lujo, de primera necesidad,

oh, poetas! No cantéis

a las rosas, oh, dejadlas madurar y hacedlas

mermelada de mosqueta en el poema

____________________________________________________________

El Autor pide al Lector diScurpas por la molestia (Su Propinaes Misuerdo)

Chilean poetics