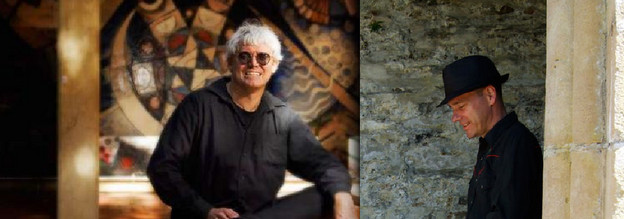

Kinsella & Milne collaborate on 'Reactor Red Shoes'

Not the building of a megaphone for bardic harmonics, nor the people’s microphone, but a dance of many feet...

I'm pleased to present here a statement by John Kinsella and Drew Milne on their forthcoming book-length poem-project, Reactor Red Shoes. The work is being published September, 2013 by Veer: bbk.ac.uk/cprc/publications/veer-books . Below the statement is an excerpt from the poem, reproduced from the typescript.

John Kinsella & Drew Milne, Reactor Red Shoes: A Statement

Here, where two writers sidle up into becoming a third party — a third-party poetics in play and with shared accountability — there is not so much a duet of voices, as a textile of give and take, warp and weft. It could be called an implied dialogue, a process, or a sharing of the soap-box, but dialogue suggests dialectic, or a legislative grind through questions and answers. Such stains of argument are entertained and found wanting here. Not for Kinsella and Milne the liberal idols of dialogue and the performance chatter of radio discussion, nor even the collage of monologues by rival Socratics. This collaborative poem shares more than argument or dialogue, building across seemingly necessary interruptions into an on-going dance.

Reactor Red Shoes is a work of poetry developed out of shared conversations that began in the 1990s, and which were brought into writing during Kinsella’s Judith E. Wilson Fellowship in Cambridge, where Milne is the Judith E. Wilson Lecturer in Drama and Poetry. For Kinsella, this was an act of presence; and for Milne, an act of social being. The writing-together took around eighteen months, from around September 2011 to February 2013. Working through Red-Green and Marxist-Anarchist difference engines, the poets shared a process of verbal and textual conversation.

Recognising that collaboration can mask individual agency, somehow privileging a more collective consciousness, the poets articulated resistances to shared personal, collective and socio-political problems. Nuclear reactors, nuclear weapons, uranium mines and the machinery for enriching uranium, to take one such problem, are omnipresent across the planet and too often silently accepted as givens. The technology of radioactivity extends into the very texts created to resist it. Protest becomes paradoxical rather than successful, a commentary rather than an act of change. This becomes the impasse Reactor Red Shoes seeks to find a way through: how might the poem generate meaningful differences in the process of reacting to the shifts and disguises of collective threats and damages?

In reading poetry that offers itself as the work of a collaborative authorship, the modern sense of private property cannot quite resist wanting to own the differences and alienate them into private arts and copyrights. Scientific papers offer themselves as collectively written proceedings. Almost all the performing arts are collaboratively performed. From the simplest architecture to the writing of our laws, from the building of spirit to the logic of capital itself, the relations of production are social. And yet, the curse of solitary production is wished upon anything called to the barre of poetry, as if even Homer, or song itself, were ever the working out of one mind and not the sociality of a people making it into writing. The fairy story of the red shoes — of dancing our way brightly to death, of treading on the loaves and politics of bread over wastes of annihilation, of the cinematic diegesis of the Powell and Pressburger film of dance, creative implosion, manipulation and cultural tyranny — is more than metaphor or symbol, becoming rather an allegory of production and its political resistances.

To write, moreover, is to enter into the language of others, and almost all forms of writing, even those that treasure hermetic privations, work out towards marks of otherness, hoping to find a collective script or public dance of language. To write as though anything written could be understood as something written by a third party — a third-party made up in the discovery of a friendship and solidarity — is at first surprising and then like a new kind of third-party politics, not least in putting to some kind of music the very differences between socialism and anarchism, or between punk and ballet, that turn out to be shared recognitions. Leaning out from the tracks of familiar treads, then, there are ventriloquised imaginings stumbling over the pulse of shared record collections, films, demonstrations and political vigils. So it is with this choreography, at any rate. Amid the limits of the available dance floor, there is a measure of tonal sympathy that refuses to sacrifice the ethos of the dancer who prefers not to stay in time.

More than one writer, then, sharing a shifting platform, rather than staging two voices constrained to become either private or public. And writing with a sense of choric plurals, a choreographic making in which a shared voicing is not about building a megaphone for bardic harmonics or the people’s microphone, but a dance of many feet, a detachment of red shoes. The dancers cannot stop to look too closely at the give and take of the floor, though they are forever pointing to the cracks evident in the grounds on which we would be standing, if we were not dancing. This dance is ghost-written too by other shifts against the accommodations of present pressures and crimson enchantments. Life rushes by, but the red shoes go on, plunging headlong into the tracks of the engulfing ecopolitical disaster melting all before our damaged eyes and ears.