Elusive justice

A review of a film to be aired in November 2011 on PBS

It happened that I screened Jonathan Silvers’s Elusive Justice just as I rewatched Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List. I regularly teach a course on representations of the holocaust in literature and film; Spielberg’s melodramatic, reductive version of the Oskar Schindler story is one of the representations my students and I discuss. Spielberg knows exactly where he wants us to look, and indeed teaches us — forces us — to see the way he wants. We see the liquidation of the Cracow ghetto from Oskar’s point of view, omniscient, Olympian, commanding: from atop a hill (where he had been riding horses with his Polish mistress), a vantage enabling him and thus us to see everything at once. This view is distinct from that of the victim of the Aktion, who necessarily saw almost nothing except the chaotic and blindingly rapid-moving terror immediately in fro nt of him or her. And to make certain that we see what we are supposed to, from the authoritative perspective we are simply given, Spielberg paints bright red (in a movie otherwise filmed in pseudo-documentary black and white) the coat of a little Jewish girl, so that we can follow her with our eyes, having no choice, and can identify with her innocence amid the guilt. It is supremely well intentioned, but nothing here is elusive. Schindler’s List marches straight toward the feelings it is designed to instigate in its viewers. There is no visual or thematic wandering. It is friendly toward sovereignty. It is about who has the power of life and death and its own flawless visual mode (strongly implying that it can after all be comprehended) makes no irony of that absolute power.

nt of him or her. And to make certain that we see what we are supposed to, from the authoritative perspective we are simply given, Spielberg paints bright red (in a movie otherwise filmed in pseudo-documentary black and white) the coat of a little Jewish girl, so that we can follow her with our eyes, having no choice, and can identify with her innocence amid the guilt. It is supremely well intentioned, but nothing here is elusive. Schindler’s List marches straight toward the feelings it is designed to instigate in its viewers. There is no visual or thematic wandering. It is friendly toward sovereignty. It is about who has the power of life and death and its own flawless visual mode (strongly implying that it can after all be comprehended) makes no irony of that absolute power.

With whatever its flaws, I prefer Elusive Justice. It is the opposite of monocultural and didactic, even though it has a strong point of view. It proposes a problem and leaves us to work through it. Absent is the laser-like focus of many filmic representations of the holocaust, Schindler’s List being just one such. Elusive Justice indicates this from the very start. Behind spare credits, we watch a German street on a rainy day in 1960s-era footage made by a handheld camera held by someone whose shoes we see and whose irregular footsteps we hear. Jonathan Silvers has made a choice: he wants us to begin with elusive justice by seeing the camera-wielding pursuer himself. The film is implicated in its problems. There is little separation of subject and object. We are in it. Silvers himself — as we will see — is in it. His predecessors were in it, and he picks up the work where they left off. We know from the start that the opening footage was made by a stalker of war criminals in an earlier era. The grainy footage implies a chain of film-making witness. Silvers has no intention of standing above.

Very soon the camera lifts and we see a German burgher, doubtless on his way home from his 9-to-5 job. But he hides his face. His camera-wielding follower has nothing to say to him as he and we move rapidly yet uncertainly behind the man. One has a sense that this is a repeated scene. The pursued is elusive, and so is the point of the scene (bravo! I say) and so, to a great extent, are the motives and expected outcomes of the pursuer. From its first moments, Elusive Justice presents us with a multiplicity of explanations. And when it’s done it will have permitted us to hear diverse voices of vengeance-minded survivors and other witnesses. Its narration’s keynote line — “There are as many conceptions of justice as there are victims of crimes” — asserts that no one voice will define that conception. Many, indeed as many as there are minds contemplating it, will be required. Following that memorable line, a pause. And then the devastating caveat: “But there are criminals who evade judgment and there are crimes that defy comprehension.” This is said, by narrator Candace Bergen in a tone that is a mixture of neutral and ominous, as we literally do not quite know what we are seeing on the screen. It prepares us well for the perplexing range of vengeant options and explanations as to why most efforts at justice have failed and why so many (including Silvers himself) continue the pursuit.

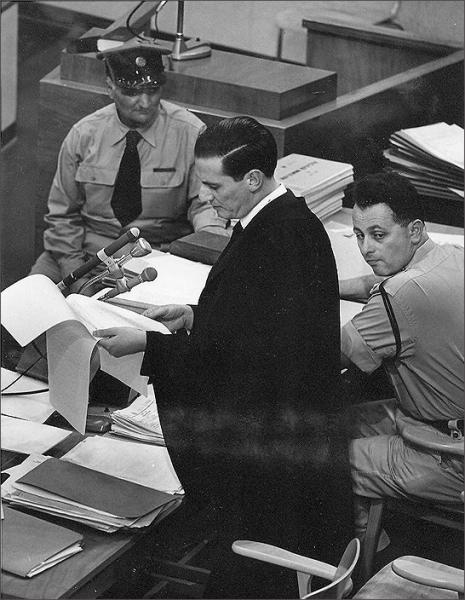

Along the way, we meet members of the Nokim group, who either did or did not successfully poison several thousand demobilized SS men in an end-of-war internment camp. “The Germans poisoned us with gas,” Yehuda Maimon tells Silvers, “So what is so terrible that we want to pay them back in the same form?” Why, in such an assiduous documentary, can we not know the extent of Nokim’s success? Many reasons, and these must be included in the film rather than edited out in favor of a summary statement: the memories of Jewish plotters themselves, now aged, vary from person to person; the Americans never released the evidence they gathered; the necessarily secretive style of such people extends to this day. And we meet Benjamin Ferencz, whose need to gather evidence from the recently liberated camps has about it the fervor of the will to bear witness. Still in his twenties, he tried his first case at Nuremberg, in which 22 war criminals who supervised the infamous Einzatgruppen were charged with the murder of more than a million people. Ferencz tells Silvers that these trials were just a “sampling” of what could have been done. Why just a sampling? Why not more? This is an old topic, but here, in the voice of the diminutive but fierce Ferencz, it is given analysis freshly: there were economic reasons, for the Allies sought to rebuild Germany more avidly than to denazify it; there were of course political reasons, as the U.S.-Russian alliance, and coordinated efforts to prosecute war crimes, collapsed in favor of routinized “cold” mistrust. Ferencz’s tone is elusive: he is proud of the aggressive and successful young lawyer he was; he is haunted by the war criminals he could never prosecute; he is angry at the speed with which the genocide was left legally behind; he is an old man now, resigned and bemused. The movement across subtopics in this film suggests a comprehensive range, but, aptly, viewers will feel disoriented, in a gray area of ethical, legal, and psychological shadows cast as wide as Europe and indeed as wide as the postwar disapora.

Shadows are a literal part of the visuality here, but of course they are also a major trope. Asher Ben-Natan and Tuvia Friedman chased down war criminals in Poland immediately after the war. Every day, Friedman remembers for Silvers, he and colleagues beat up between 15 and 20 former Nazis. He describes it as a “private effort to do what official institutions would not.” The dim light shed by Silvers’s cameras do not dissipate the shadows of Vatican seminaries and vaulted archives, as he goes after William Gowen who went after evidence of hundreds of Croatian war criminals funneled to Argentina through the Vatican’s power to provide out-of-bounds hiding places. Even the oft-told tale of the Mossad’s discovery of Adolf Eichmann in Argentina is given new complexity by the film’s attention to ambiguities in the plan, its ultimate legal intention, and the strangely alluring obscurity of the first Mossad photographs, taken with hidden cameras, of Eichmann — or it is Ricardo Klement, or Otto Eckman? — a conformist man blurred, turning rapidly away, blending into to the German émigré community which flourished there under Juan Peron. The very act of Israeli super-discernment — picking out Klement as from a police book of bad mugshots — is an extra-legal leap. Even the testimony of Ferencz, he who worked in the belly of the official prosecutorial beast, has the feel of the memory of an outsider, someone not quite doing what he was supposed to.

Silvers locates Alois Kaufman, a child survivor. The Nazis dubbed him a juvenile delinquent and sent him to a psychiatric hospital where he was to meet the fate of disabled children who were, through euthanasia, to be delivered from strains they put on society and from the opportunity to procreate. After the war, nurses, orderlies, and wardens were permitted to go into public service. Silvers documents Kaufman’s frustrated pursuit of these criminals. And apparently what we see at this point in Elusive Justice is the result of the director’s having forced or bamboozled his way into the institute’s archives, where we find hundreds of jarred pickled human brains, among them at least one that once filled the head of a child Alois Kaufman had befriended during his internment there. Not enough for Silvers. He then locates Heinrich Gross, former head of the murderous clinic, and interviews him for this film. His responses — typified by “If you were a staff member and refused to participate, you would be killed by the Nazis” — cast a further shadow. “No one took an interest in our story,” says Alois Kaufman. But Silvers’s very presence in this part of the film — we know he is there somewhere behind the camera; we know he is part of the hunt, interviewing Gross, breaking into forbidden spaces — is a good although once again ambiguous answer to Kaufman’s fears.

As it happens, my odd-seeming comparison of Spielberg and Silvers is particularly apt. A doomed girl in a red coat, whom we cannot ignore, makes an interesting reappearance. Gavriel Bach, deputy prosecutor in the Eichmann trial and later a member of the Israeli Supreme Court, is here not to affirm super-articulateness and clarity. As he elicited testimony from one of many witnesses to Nazi atrocities, a man tells of his separation from his 3-year-old daughter. She was wearing a red coat, and the man, in Israeli court with Bach standing in front of him, describes his final view of her: a red coat, moving further away, getting smaller and smaller. Bach had recently purchased for his own daughter, at two-and-a-half, a red coat. As live television cameras rolled, Bach went into deep memory, somehow co-temporaneous with his witness. The trauma of the merged “memory” “cut off my throat completely,” as he tells Silvers, and he was rendered speechless in court for three or four long minutes. Yes, Bach is an able and appropriate talking head for a film on this topic. That is no doubt why Silvers traveled to interview him in the first place. But the power of his appearance in Elusive Justice derives from the power of that inability to speak. If Spielberg’s girl in red indicates an aesthetic of insistent clarity, the capacity to see and say exactly what happened, Silvers’s film will become part of a powerful counterargument to that mode: to begin to know what happened, one must reckon with its essential elusiveness.

As it happens, my odd-seeming comparison of Spielberg and Silvers is particularly apt. A doomed girl in a red coat, whom we cannot ignore, makes an interesting reappearance. Gavriel Bach, deputy prosecutor in the Eichmann trial and later a member of the Israeli Supreme Court, is here not to affirm super-articulateness and clarity. As he elicited testimony from one of many witnesses to Nazi atrocities, a man tells of his separation from his 3-year-old daughter. She was wearing a red coat, and the man, in Israeli court with Bach standing in front of him, describes his final view of her: a red coat, moving further away, getting smaller and smaller. Bach had recently purchased for his own daughter, at two-and-a-half, a red coat. As live television cameras rolled, Bach went into deep memory, somehow co-temporaneous with his witness. The trauma of the merged “memory” “cut off my throat completely,” as he tells Silvers, and he was rendered speechless in court for three or four long minutes. Yes, Bach is an able and appropriate talking head for a film on this topic. That is no doubt why Silvers traveled to interview him in the first place. But the power of his appearance in Elusive Justice derives from the power of that inability to speak. If Spielberg’s girl in red indicates an aesthetic of insistent clarity, the capacity to see and say exactly what happened, Silvers’s film will become part of a powerful counterargument to that mode: to begin to know what happened, one must reckon with its essential elusiveness.

- -

I am grateful to Sam Hughes and John Prendergast who commissioned this review for the Pennsylvania Gazette and will be publishing it there very soon.