Dennis Brutus's creative activism

![Dennis Brutus testifying before the United Nations in 1967 on behalf of the South African Nonracial Olympic Committee as well as South African political prisoners. [African Activist Archive]](https://jacket2.org/sites/jacket2.org/files/imagecache/wide_main_column/big32-131-26C-98-african_activist_archive-a0b3w6-a_14380.jpg)

Kaia Sand

Jules most recently wrote about poetry, dissent, and the Olympics, and in this capacity, the late South African poet Dennis Brutus was legendary.  Despite the fact Brutus said he was “never a good athlete,” he turned to sports as a focus for his activism (“I was reasonably good at organizing,” he explained), and began organizing sports competitions in the 1940s at the high school where he taught (Brutus 38). Through his affiliation with a number of anti-apartheid activists, he homed in on the Olympics with his sports-organizing talents, finding a contradiction between the Olympic charter (which forbade racial discrimination by participating countries) and the apartheid government of South Africa. In the early 1960s, he helped launch the South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee (SANROC), pointing out that the current South African Olympic Committee was illegitimate because its exclusion of non-white athletes defied the Olympic charter. This assertion of SANROC's legitimacy helped him gain the ears of Olympic officials over the years. "It turned out that if you were part of an Olympic committee and wrote to the IOC [International Olympic Committee], they were supposed to respond to you,” Brutus recalled in a memoir (132).

Despite the fact Brutus said he was “never a good athlete,” he turned to sports as a focus for his activism (“I was reasonably good at organizing,” he explained), and began organizing sports competitions in the 1940s at the high school where he taught (Brutus 38). Through his affiliation with a number of anti-apartheid activists, he homed in on the Olympics with his sports-organizing talents, finding a contradiction between the Olympic charter (which forbade racial discrimination by participating countries) and the apartheid government of South Africa. In the early 1960s, he helped launch the South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee (SANROC), pointing out that the current South African Olympic Committee was illegitimate because its exclusion of non-white athletes defied the Olympic charter. This assertion of SANROC's legitimacy helped him gain the ears of Olympic officials over the years. "It turned out that if you were part of an Olympic committee and wrote to the IOC [International Olympic Committee], they were supposed to respond to you,” Brutus recalled in a memoir (132).

Around the time SANROC was formed, Dennis Brutus was banned in 1961 from gathering with other people through the Suppression of Communism Act, arrested in 1963 for defying the ban because of his SANROC organizing, shot when he tried to escape (and nearly died after a white-only ambulance turned him away), and imprisoned in Robben Island from 1964-1965. His prison term overlapped with Nelson Mandela.

Brutus was subjected to a tangle of apartheid government bans, including the Sabotage Act, which banned him from writing and publishing. His poem “The Mob” addresses one brutal outcome of the Sabotage Act when a “white crowd ... attacked those who protested on the Johannesburg City Hall steps against the Sabotage Bill” (Brutus 95). “O my people” Brutus writes and repeats. “O my people/ what have you done.” This enjambment always startles me, the complicated compassion: although the speaker fears the attackers throughout the poem, he longs for their humanity.

Mina Loy wrote that Gertrude Stein gave “fresh significance to her words, as if she had got them out of bed early in the morning and washed them in the sun” (qtd in Burke 318). While this makes sense as a description of Stein's insistent phrasing, until I returned to the passage this week, I had recollected it as Stein describing Loy's language, since Loy salvaged words from the dictionary, championing diction that was archaic, precise, startling. And it is in this way that Brutus's diction has always resonated for me as washed anew. In his poem “The Mob," the phrase “saurian-lidded stares”–which seems both to describe the speaker's “irrational terrors” and the crowd that attacked protestors–is smooth with the soft, curving sound of “saurian.” Disarming. While “reptilian” is a near replacement, that word is more physically demanding to mouth, and slack with easy connotations. That these attackers could be so smooth in their cruelty is part of the pain in the poem. Brutus's choice to defamiliarize language creates small disruptions to his evenly rhythmic and descriptive verse. Likewise, disruptive creativity was a hallmark of his sports organizing in years to come.

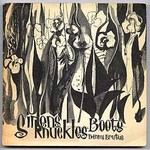

The Sabotage Act criminalized poetry for Dennis Brutus. While he was in prison, he was charged with “with the crime of publishing a book of poetry.” While he was “going to plead guilty” (which meant a longer sentence) to the publication of Sirens Knuckles Boots, the charges fell apart because of his failure to remember the date when the book was published in Nigeria (“part of the process of agony was that my mind was becoming extremely unreliable and particularly my memory” (87)), and thus whether the Sabotage Act had already been leveled against him during those dates (155).

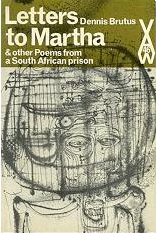

The Sabotage Act criminalized poetry for Dennis Brutus. While he was in prison, he was charged with “with the crime of publishing a book of poetry.” While he was “going to plead guilty” (which meant a longer sentence) to the publication of Sirens Knuckles Boots, the charges fell apart because of his failure to remember the date when the book was published in Nigeria (“part of the process of agony was that my mind was becoming extremely unreliable and particularly my memory” (87)), and thus whether the Sabotage Act had already been leveled against him during those dates (155).  “The image of Robben Island in my mind was one of terror, Brutus writes, and a number of his poems address those experiences,) including several sequences--“Robben Island Sequence,” “Letter to Martha,” “Endurance,” “On the Island,” among others (71).

“The image of Robben Island in my mind was one of terror, Brutus writes, and a number of his poems address those experiences,) including several sequences--“Robben Island Sequence,” “Letter to Martha,” “Endurance,” “On the Island,” among others (71).

After he was released from prison, he continued organizing for boycotts against South Africa in international sporting competition through the International Committee Against Racialism in Sport (ICARIS) as well as SANROC. The boycotts were successful: in 1970, South Africa was expelled from the International Olympic Committee, and by the 1980s, South Africa national teams were isolated in many sports, including cricket and rugby. Brutus and other organizers succeeded in demonstrating to nations outside South Africa how the apartheid system extended to sports. To compete against the all-white South African teams was to engage the apartheid system.

Brutus describes his tactical decisions in his memoir, compiled in the volume Poetry & Protest, which also gathers essays, documents, and poems, and from which I've gathered many of the details for this commentary. I recommend reading this volume, which conveys the indefatigable commitment Brutus and others had to put forth through meetings, letters, and the everyday work of organizing.

Brutus describes his tactical decisions in his memoir, compiled in the volume Poetry & Protest, which also gathers essays, documents, and poems, and from which I've gathered many of the details for this commentary. I recommend reading this volume, which conveys the indefatigable commitment Brutus and others had to put forth through meetings, letters, and the everyday work of organizing.

I'd like to highlight here some of the notably creative tactics.

In one instance, he describes meeting at a pub with the anti-apartheid committee at Oxford in the late 1960s in the hope that they would disrupt a rugby match between the all-white South African national team and Oxford University. He was disappointed in their meager turnout when he found “four or five of them smoking pipes and drinking sherry.” They surprised him come match day, when, one hour before the scheduled start, the slogan “Oxford Reject Apartheid!” appeared on the grass, and the rugby match had to be cancelled. The night before, organizers had “poured huge drums of weed killer” to spell those words, and it remained invisible until the next day when the grass deadened into the slogan. (136).

Dennis Brutus himself disrupted a 1971 tennis match in Wimbledon involving white South African Cliff Drysdale by sitting on center court. He was arrested, and his case was appealed to the House of Lords, who ruled in Brutus's favor (Brutus 136).

Creative tactics disrupted both cricket and rugby matches in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. In his article “Apartheid on the Run,” Rob Nixon recounts a string of actions. In one case, an activist entomologist bred 70,000 locusts, threatening to unleash them on the cricket field where, he warned, they would “consume 112 pounds of grass in twelve minutes” (68). Nixon also describes how “buckets of glass and thousands of tacks and fishhooks were sometimes strewn across the rugby field.” In another instance, a cricket field was saturated with oil. Another tactic was Operation Wide Awake: activists would create commotion throughout the night near planned matches. Nixon describes the cancellation of a 1981 rugby tour in New Zealand when a “a World War II pilot forced the cancellation of one match by stealing a fourseater Cessna and threatening to dive kamikaze style into the packed grandstand” (Nixon 81).

The point was to make competing with South African all-white national teams untenable, or at least, grating, thus exerting pressure on the apartheid government by threatening the popular nationalist activity of sports. If matches did proceed, Nixon writes, “demonstrators drew on backup tactics to insure that playing conditions were unendurable. They fired off smoke bombs, paint bombs, and flashed mirrors in players' eyes. Scores of whistle-blowing activists infiltrated the stands” (81)

Such creative tactics helped draw the attention of international media to the injustice of apartheid.

“The problem, first of all, is to create some breathing room, to loosen the bonds that enclose spectacles within a form of visibility,” explains philosopher Jacques Ranciere in a 2009 Art Forum interview in which he discussed his idea of “dissensus.” Acts of dissensus disrupt “state of things,” or the sensible. In this way, activists organizing the international boycott on sports disrupted acceptance of the apartheid system.

“The main enemy of artistic creativity as well as of political creativity is consensus--that is, inscription within given roles, possibilities, and competences,” said Ranciere (263). Dennis Brutus's leadership in sports activism brought him into the realm of political creativity, as well as artistic creativity, in order to disrupt any consensus around a cruel status quo.

works cited

“Art of the Possible: Fluvia Carnevale and John Kelsey in Conversation with Jacques Ranciere." Art Forum. NY: March 2007.

Brutus, Dennis. Poetry & Protest: A Dennis Brutus Reader. Ed. Lee Sustar and Aisha Karim. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2006.

Burke, Carolyn. Becoming Modern: The Life of Mina Loy. NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1996.

Chan, Paul. “Fearless Symmetry.” Art Forum. NY: March 2007.

Nixon, Rob. "Apartheid on the Run: the South African Sports Boycott." Transition, No. 58 (1992), pp. 68-88

Moxie politik