Reading Resistance at the Olympic Tent Village

A conversation with Mercedes Eng

Jules Boykoff

In my last post I wrote about poets’ involvement in activism around the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver. One poet who was active during the Olympics moment was Mercedes Eng.

Mercedes Eng explores racialized oppression — locally, on the West Coast, nationally, and internationally — and how this oppression is underpinned by colonizing language and racist representation. Her first chapbook, February 2010, is a poem set in the context of the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics and is a thinking through and responding to the media and advertising, censorship, art, nationalism, diversity of tactics, and First Nations land rights. Her second chapbook, knuckle sandwich, juxtaposes text from local mainstream media coverage of the missing and murdered women of Vancouver with reportage of the Canadian “liberation” of women in Afghanistan in order to explore state violence against racialized women. She works collaboratively with Press Release and Standard Ink & Copy Press poetry collectives. A current creative project considers her lived experience with sex-work in the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver, using non-standard English to explore and to resist the ways in which victimhood is constructed.

Recently I had to good fortune of corresponding with Mercedes about her involvement around poetry and activism during the Vancouver Games.

JB: Poets played an important role in anti-Olympics organizing in Vancouver. Can you please describe your involvement with poetry and public space during the Olympics convergence? Along the way, can you please talk about reading poetry at the Olympic Tent Village?

ME: In the weeks preceding the Olympics, I contributed to an anonymous chapbook of anti-Olympic poems called Survalliance, put out by Press Release. There was a lot of discussion over Cultural Olympiad funding, and the idea of an anonymous text, and one produced without funding, was really cool. It was exciting to see how the chapbook circulated. Performance artist Skeena Reece read the chapbook to jazz music on a Cultural Olympiad stage, then she put on a black bandana and said, "these are my red mittens." The red mittens, embroidered with white Olympic rings, were quite a hot commodity during the games, at one point selling out at the Hudson’s Bay Company, the official Olympics store.

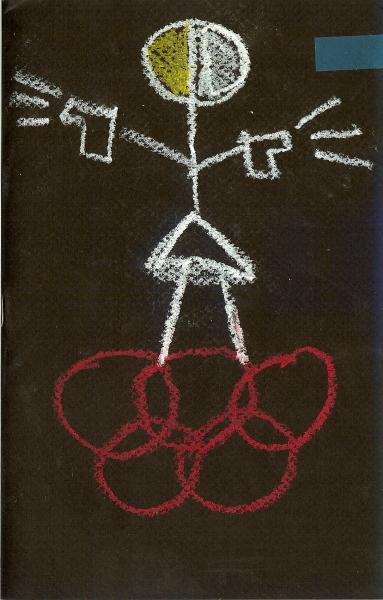

My mind was on fire during the Olympics. I couldn't stop writing about everything entering my field of vision. I went to the rally the night of the opening ceremonies – my first, and I was scared and excited and it didn’t seem real that the Olympics were finally here. It didn’t seem real two days later when I participated in the Reading Resistance at the Olympic Tent Village (organized by Ivan Drury and featuring Brad Cran, Cynthia Oka, Dorothy Trujillo Lusk, Maxine Gadd, and Reg Johanson) at 58 West Hastings, an empty lot owned by condo developer Concord Pacific that was leased to VANOC as a parking lot for the Olympics. Since the Olympic bid, homelessness has nearly tripled in the GVRD, while real estate and condominium development in the Downtown Eastside is outpacing social housing by a rate of 3:1, so the securing of 58 West Hastings as a public space by social justice groups and individuals, was important in terms of where the land is, and who (officially) owns it. Tent village was an on-going protest against homelessness, a reclamation of a common, a city from the ground up where people ate, sang, slept, talked, cooked, recycled, got conscious, and read, wrote, and heard poetry.

I’d never done a reading in this kind of a space, as my previous readings took place in academic or literary settings. To hear my voice uncontained by walls, to feel brick and mud beneath my feet, under the stars at tent city in the Downtown Eastside was unlike anything I’ve ever experienced. I owned my voice, and I called — to the women I worked with, those living and dead, to the women working now, to the community these women are a part of — and called out the cops, the state, the public who chooses to look the other way.

JB: Part of what’s energizing about the Olympic Tent Village and the Reading Resistance event you described is the fact that they created myriad micro-moments of communication between people who might not otherwise be in conversation. What have poet-activists in Vancouver done with this creative momentum in the wake of the 2010 Winter Olympic Games?

ME: For me, the momentum meant thinking, writing, and producing with a wider knowledge and with more people. The ability, the opportunity, to come into contact and talk with such a multiplicity of individuals and social justice groups at the Tent Village, heIped me to understand how the issues I was trying to address in my poetry (a lot of my work is about the missing and murdered women from the Downtown Eastside) connected to broader struggles. These interactions also galvanized me into getting my body on the ground at marches and rallies and to learn about organizing. So I began to work collaboratively, in terms of writing poetry and making books, and in organizing with others. I think for a lot of us the Olympics were a learning process, and that the lateral solidarities that enabled the actuality of tent city created a new public, a space in which to learn and form our own relationships.

I see this creative momentum manifest in the coalescence of individuals from different spaces/places into various kinds of groups. For example, I know some poets — or people I would tend to position as poets — that participated in the poetry, critical debate, and protest that occurred during the Olympics have started a discussion group to consider protest tactics in order to connect to on the ground action more concretely. And there’s a group of community organizers — or people I would tend to position as community organizers — who formed a poetry collective during the Olympics and who now sometimes do their social justice work as poets.

Moxie politik