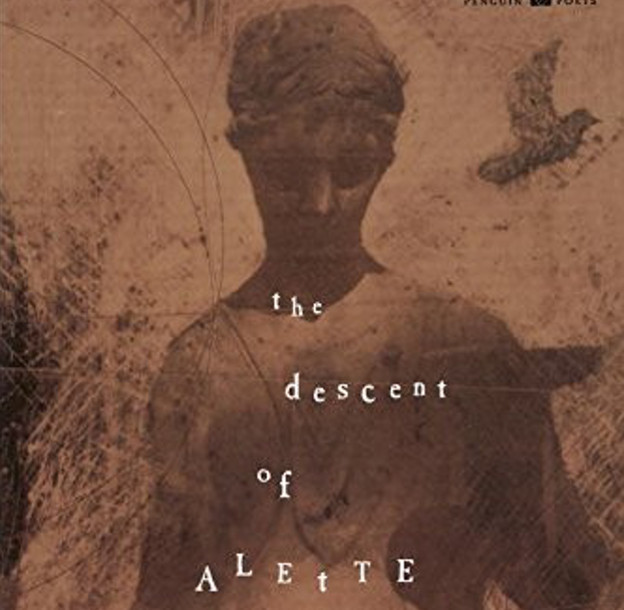

Alice Notley's 'The Descent of Alette'

To reimagine a genre can be to imagine a better world.

Alice Notley’s The Descent of Alette is a book-length work with an avowedly feminist aim: to write a woman-authored epic poem with a heroine in a genre she characterizes as predominantly “male-centered — stories for men about a male world” (Notley, Homer’s Art). The protagonist and the other denizens populating Notley’s underworld are banished as undesirables from the city “above the ground” and are condemned to ceaselessly ride the underground subway without the means to buy passage back to the city. Alette, who remains unnamed until the fourth and final book of the text, journeys below a similarly unnamed city where one man is in charge of the oppression:

“A man who” “would make you pay” “so much” “to leave the subway”

“that you don't” “ever ask” “how much it is” “it is, in effect,”

“all of you, & more” “Most of which you already” “pay to

live below” “But he would literally” “take your soul” “Which is

what you are” “below the ground” “Your soul” “your soul rides”

“this subway” “I saw” “on the subway a” “world of souls”

The man is the “tyrant,” who controls the underground inhabitants and is the embodiment of the social system that structures this economic and spatial hierarchy. Alette, awakening in medias res on the subway, is on a self-proclaimed mission to find the lost, first mother when she is given an additional quest by a guardian owl to kill the tyrant.

Alette narrates her undertaking in an invented meter of quotational phrases. The heroine’s voice, citing oral tradition, invoking the subway ride’s rhythmic starts and stops, registers the threat that, like the constitutive, between-comma gaps that mark the line, her steps from platform to car, from cavern to grotto, may gape into an uncrossable chasm. Throughout, she encounters supernatural beings that include men with animal faces in business suits; tangles of snake-bird-women bodies; burning bodies; headless women; maimed soldiers; and unattached body parts such as the single, sentient eyeball that rolls through the subway cars. Overcoming peril with valor, Alette ultimately must yank the tyrant’s arm-limb-plug from the underground network, after which the subjugated bodies of the subway free themselves from their kept quarters with the tenuous promise and task of a new way of life ahead of them.

In the final scene of the poem, after laying down the tyrant’s dead body, Alette warns the newly emerging crowd of people:

“‘This is not really” “his body,’” “I said to them,” “‘The structure

we’ve just left — “those around us —” “this city —” “how we’ve lived,”

“is his body’”

Alette echoes Adrienne Rich’s call for systemic transformation “if we are not going to see the old political order reassert itself in every new revolution.” “This city” is cast as the material and ideological structure holding oppression in place. A person interjects a question into a group discussion, “‘But can’t we make” / “something new now … ”

The answer is an urgent yes. The book’s end is a beginning as Alette watches “many” “forms of being” / “I had never” “seen before” “come to join us” “or come to join us / once more” “Whatever,” “whoever,” “could be,” “was possible.”

Epic Engagements