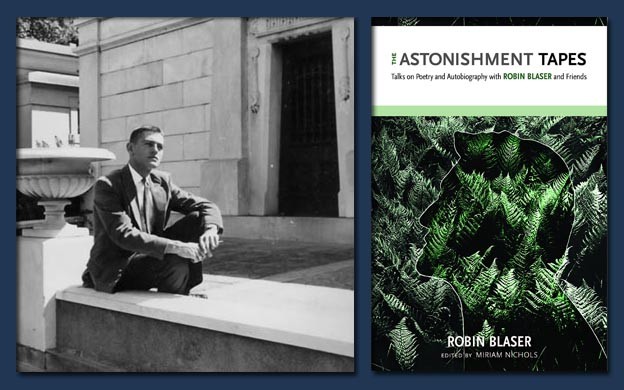

In his element

A review of 'The Astonishment Tapes'

The Astonishment Tapes: Talks on Poetry and Autobiography with Robin Blaser and Friends

The Astonishment Tapes: Talks on Poetry and Autobiography with Robin Blaser and Friends

Robin Blaser is in his element in these monologues in interview format — personable, pedagogic, and himself a “high-energy construct,” to not-quite-cite Charles Olson. By virtue of this book, the reader experiences Blaser as a unique force field of magnetic knowledge and charismatic charm. He is at home among the poets, themselves practitioners and friends, meeting in 1974 at someone’s house in Vancouver. The agenda is mixed: the taped sessions from which these talks are transcribed were apparently proposed by Warren Tallman to constitute or contribute to Blaser’s autobiographical memoir, and probably to dig into the complex nexus of a famous triad: Robert Duncan, Jack Spicer, and Blaser. Their comradeship, quarrels, spites, and splits (among those involving other intimates) are one tale of the formation and impact of the “Berkeley” or “San Francisco Renaissance” in the New [North] American Poetry, a poetics and practice — with its accompanying lore — that energized these Canadian poets in distinctive ways.

As performer, talker, essayist, and poet, Blaser will not stay domesticated in literary history. The 1974 Vancouver tapes are therefore rangy, suggestive, allusive, and metamorphic. So the other part of the agenda for these meetings is both more buried and irruptive. Blaser is direct: “An autobiography is as much the intellectual loves as the personal loves.”[1] As if he were running a high-level seminar in the humanities and poesis, Blaser immerses his audience in poetics and poetry from Dante to Shelley, Mallarmé to seriality, touching on such poets as Olson, Pound, and Levertov, but also encompassing Western poetic and philosophic traditions. Blaser wants, needs, and desires to talk broadly, taking the defining interests of Duncan, Spicer, and himself as exemplary of the problematic of Western civilization after “religion” loses its binding force: what can the human be ontologically and epistemologically in the post-humanist period? And what, therefore, are the tasks of poetry? Indeed, Blaser’s Dantean framework became quite clear to me in reading this book — not sure why this book particularly, but there it is. In fact, Blaser is one of the striking users of Dante among contemporary poets, but unlike John Kinsella’s or James Merrill’s, his Dante is somehow distributed into and saturated within “Image-Nation,” the serial poem pulsing at irregular intervals through his collected poems, The Holy Forest.

At his best in these tapes, Blaser is like the angelic imp of poetry itself, offering dynamic and inspired discussions of “wild logos” (e.g., 190, 197), of poetry as “noetic” (knowledge-bearing; 81, 192), and offering intense broad-brush interventions in the history of ideas. The slight abrasion between holding Blaser strictly to the fuss and minutiae of personal autobiography (which leads to some clarification at times — the “straight story,” as Tallman says, straight-faced) and Blaser’s far grander aspirations to articulate his life as one poetic allegory of soul-making are part of the intensity and charm of this book. Blaser’s task is to embody the sense of — yes — astonishment, blessing, and ethical order without dependency on religious revelation.

The book gives a little window into the workings of a poetry group, and the findings are incomplete but recognizable. There are moments of intense seriousness and there are moments of jocular undercutting. Tallman’s antic moments sometimes grate. But withal, this is a necessary book for the poetics of interrogative openness in language. Blaser’s career and the stories generated are wonderful artifacts all their own: life on a railroad siding somewhere in Idaho, a gay boychild from a strivingly literate family on the frontier, a mixed-up mythos including Catholicism and a touch of the Book of Mormon, are just some strands braiding up a major poet of critical sensibility, urbane sophistication, and invincible intelligence. The mutual self-fashioning among Spicer and Duncan and Blaser constitutes another key story, all under the influence or thrall of Ernst Kantorowicz, a professor of medieval intellectual and political history who came from Germany to the US in the forced Jewish diaspora of the Nazi-fascist era. Striking to me is Blaser’s infinitely patient loyalty to both Duncan and Spicer: no matter what provocation, he will speak no evil of either. “Jack,” particularly, has a talismanic function for Blaser — something between a guardian saint and an exemplary warning, a bleeding statue one puts in a niche in one’s house.

Insofar as a review is a guide to reading, it’s worth noting that in these discussions, a word that takes some transposition for 2016 ears is Blaser’s use of the term “manhood” — a non-gendered synonym for the highest human sensibility (the “man” in “human” is a useful mnemonic). It is really “personhood,” never meant as a gender-exclusive term. His interlocutors are never only men from this group — women are full participants — and Blaser himself has a genderqueer soul.

Miriam Nichols’s editing of these transcribed tapes is a marvel of discretion and intelligence, informed by her important work on Blaser — her edition of The Holy Forest and of The Fire, his essays; her book Radical Affections, “On the Poetics of Outside.” (The full transcription of these tapes is held in the Contemporary Literary Collection at Simon Fraser University.) Nichols offers about as full a description and set of apparatuses as one could desire: exact bibliographic account of the materials as available (disintegrating, poor-quality audiotapes); the reasons for her specific selections from these tapes, along with a useful summary of transcript materials not included in this book; excellent thumbnail sketches of the participants and of the allusions Blaser makes to friends and thinkers, poets, political figures (e.g., who is Hugh of St. Victor? and so forth); and extremely deft annotations in her endnotes. Among the other decisions enhancing the book’s scholarly usefulness are the categories for “Blaser” in the index: poetics, poetry and philosophy, poetry and politics, poetry and religion, relations to other writers, romantic relationships, works by, and then a set of “Blaser and places,” including Berkeley, Boise, Boston right through the alphabet.

There are so few scholarly glitches that I feel churlish obeying the convention for reviewing these kinds of texts and noting the very few that I found. In the list of names there is no entry on Dante, although of course he appears repeatedly in the index; the same is true of James Joyce. It is, however, much more valuable to have annotations for now obscure friends and acquaintances once on the scene than to have sketches of these extremely well-known people — but nonetheless it seems that only a few such major figures are missing and could have been present. As for literary history, a citation by Thomas Nashe (1567–1601) is attributed to poet and novelist Mary Butts (279–80, note 3). “Brightness falls from the air / Queens have died young and fair” are lines any poet would long to have written, but they actually come from Nashe’s “A Litany in Time of Plague.” Finally, in the very important “I, John, saw” discussion between Blaser and Duncan, the crucial, exact citation that Nichols needed here is from H.D.’s Trilogy, in “Tribute to the Angels” (first published 1945), in sections 3 and 43.[2] The line signals a crucial motif in H.D.’s critique of the closing of the book (that is, the Bible). This closure is one John declared along with his witnessing, and in her text, this line foregrounds H.D.’s resistance to John’s claim and her insistence on the sense of continuing revelation that animates her poetic work. Of course, Duncan knew well this specific work of H.D., and both he and Blaser held to the sense of continuing revelation.

Part of Blaser’s charisma is his joy: a sense of having been endowed with “absolute blessing” (203) and of offering back “love” (218). Another endowment is his wicked and frank wit. We are lucky to have the traces of Blaser’s astonishment and poetic intelligence preserved in this text, with thanks to the patient editing and scholarly understanding of Miriam Nichols.