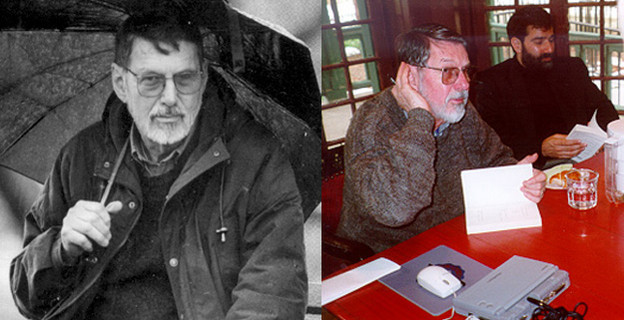

Robert Creeley at Kelly Writers House, 2000

Editorial note: This interview took place on the second of two days of visits by the late Robert Creeley to the Kelly Writers House in 2000 as part of the Writers House Fellows program, which brings three writers to the University of Pennsylvania’s campus each spring for close interaction with students, faculty, and other literary aficionados. Creeley’s prolific poetic work has garnered praise from the likes of William Carlos Williams, Allen Ginsberg, and Edward Dorn, while his editorial expertise has graced such publications as The Black Mountain Review and Origin. His countries of residence (Spain, France, Guatemala, Finland, and others) were nearly as diverse as the array of fellowships and awards that he received in his lifetime. Video and audio recordings of Creeley’s visit can be found here. — Kenna O’Rourke

Al Filreis: Before Bob Creeley enters the room, I’m going to talk to those fifty or so friends, poets, teachers, students, neighbors, colleagues, friends from over the ocean who are tuning in over the web this morning. Let me give you preliminary information: it’s 10:30 eastern time, so good morning. Bob Creeley is here as a Writers House fellow, and in a moment we’ll start a discussion with Bob and the engaging people here at the Kelly Writers House on the campus of the University of Pennsylvania. Everyone out there is distinguished and individuated in our minds — but hello particularly to friends Jackson Mac Low in New York and Marjorie Perloff in Los Angeles. For Marjorie, it is early. Get your coffee, Marjorie. And to those forty or so who have come to be part of a live, face-to-face session: welcome. We really enjoyed Bob Creeley’s visit yesterday at the Writers House as part of the Writers House Fellows program, and we’re looking forward to this session this morning. No introduction is needed. Well, an introduction is required, but we did it last night, and if you want it, you can do what Bob did from his hotel, which is simply click on the webcast recording of it and listen to my introduction.

I have two questions to start. But before that, as a kind of preamble, Bob wants to show us some cool tech that he is into. Bob is clicking and pointing. You want to describe what you’re doing?

Creeley: Well, it always was a question, with respect to the ways I wrote, or the mode, not the mode, the so-called structure of the prosody. I used Williams’s proposal: “break into the middle of some trenchant phrase,” et cetera. I had really misread his format. I thought, for example, that he paused distinctly at the end of each line. He got, therefore, a syncopated rhythm from doing that, and then when I heard him read actually, on early records at least, he did not do that. He read through the line ending without pause. So, one of the consistent questions about the way I wrote was: you would make those pauses at the end of lines, but are you reading into the poem those intervals? And I insisted that I wasn’t. It’s simply a personal insistence. Then, with an early speech-synthesizing program called Monologue, which did happily stop at the ends of lines, I was able to demonstrate without any, you know, no hands. This cranky, crunky voice would read very well, would read my poems excellently. So, I could make clear it wasn’t me doing it, the machine was doing it, which was a curiously very useful cause. It ended that argument, frankly, once and for all. It’s a wonderful voice.

Filreis: Where’s the speaker?

Creeley: It will come. I still have to get the appropriate file. It doesn’t use the syncopation quite at all very much, but I am also interested in pacing, what the intervals apparent are. Again, as I say, this voice is in no way expressive or interpretive. I was visiting in a pleasant school in Dobb’s Ferry in New York and one pleasant teacher there, a Chinese-American, said, “Sounds just like my uncle.” So here we go. Speak.

[Computer monologue reads inaudibly.]

Creeley: Wait a minute, I’m sorry. Let’s start again.… Come on, speak. Why do you never speak? … I don’t know. Maybe it’s tired.

Filreis: That ended that argument once and for all.

Creeley: Wait a minute, we’ll try again. Come on, I want to get it louder.… Louder, louder.… As loud as it can go.… Patience. Resume.… Speak.

[Computer monologue reads poem.]

Filreis: That was monotonous Robert Creeley.

Creeley: This program also allows you to slow down the tape and shift the pitch. It’s rudimentary. This is noted as a US English male, H.L.

Filreis: H. L.?

Creeley: H. L. Mencken or something.… Okay, that’s enough.

Filreis: All those lines are end-stops?

Creeley: Yeah.

[Triumphant computer sound.]

Filreis: Whenever you don’t want Bill Gates, he appears. So your sense of the line, your sense of rhythm at the level of the line: I wanted to ask you a couple of questions about William Carlos Williams. Was that in the American grain, that voice?

Creeley: Yeah, I wanted something that would not express or read into the language overtly. I didn’t want it to be necessarily a drab voice, but I wanted it to be a saying of the words that would be dependent upon their pattern rather than my interpretation of it. To me, one of the problems in poetry — at least one that my particular company spent a great deal of time on — was the question of the register of the text and how that might be used as an information for the person reading it, presuming he or she would be hearing it in his or her head or reading it aloud. Olson, for example, spends a lot of time on this problem. Duncan, literally, toward the end of his life, acquires what’s then a state-of-the-art word processor so he can actually set his text and have it actually reproduced as the text of the published book, Groundwork. It was not In the Dark, but Before the War is thus composed. Denise Levertov has the same concerns. Paul Blackburn, et cetera. I don’t know why it became such a remarkable question for us. But it really is a difference between our company and that just previous. The Objectivists, for example, seem to have these concerns but do not particularly involve them in their own recital or their own reading of their own work.

Filreis: Yesterday, you said that for a long while, at the beginning, you were using a typewriter, and a particular typewriter that you needed. And then you mentioned that Allen Ginsberg had genially advised you to get rid of the typewriter so you’d be more mobile. Did, at first, the acquisition of the typewriter as the means of writing have anything to do with Williams, for instance, who was addicted to his typewriter? I guess the second question is: what was it like when you got rid of the typewriter?

Creeley: Well, the typewriter, initially, was a great way of freeing oneself from the personalism of one’s own handwriting. I was distracted by the way I wrote. Not that I wrote incompetently, but I began to be obsessed with the nature of my handwriting, which was certainly not the point of what I was doing. I wanted something that would instantly, so to speak, objectify these words I was putting in strings. I wanted to have something, again, that would not be informed by my personal disposition in handwriting. I wanted the words to be objectified, to be actualized by being generally characterized as typewriter fonts permit, and be there on the paper as something apart from my head or my personal, physical touch. I wanted them to exist in that sense by themselves. It’s nothing particularly vatic or mystic. I wanted to be able to look at them the way I would look at them on a page of print.

Filreis: So what happened when you got rid of the typewriter?

Creeley: I think by that time, that was ’63 or so, by that time I had been writing more or less — I began writing in the late ’40s — so it had certainly been fifteen years of habit. At that point, what was far more useful to me was a means of collecting and/or composing in any kind of physical circumstance. If you have suddenly an impulse or some inquiry of some way of wanting to get something done, and you have to go look for the typewriter, it’s awkward. So, this ability to use quick handwriting, that was very, very useful.

Filreis: And now the Libretto allows you to do something like that?

Creeley: With Libretto this morning, for instance, I could check mail, get a pleasant set of letters from friends in various parts of the world, I could read a newspaper — there’s a great attack on Bush’s provisions for public health in Texas and all the statistics pertaining — I could download the program that we were just listening to, I could play games.

Filreis: Or you could write?

Creeley: No, I didn’t write this morning. I wrote last night a quick letter home. Phones I love, too, the intimacy of a physical, real voice is obviously wonderful. But there are times, again, in a rush, when one wants — what was the flight number, what is the cell phone’s number, things of that sort which are far more simply located in an email than they are, let’s say, by voice or where did I put the paper.

Filreis: Speaking of the phone, I’ll invite the fifty or so out there listening and viewing us, to call if you have a question and want to talk analog to Bob Creeley.Let me ask you another Williams question, and then I want to turn to Bob Perelman, who has a question, and then open it up even further.

Creeley: Get a shot at Bob. Phones are lighting up.

Filreis: Yes, send fifty dollars to the SUNY-Buffalo poetics program. It needs your support. Make the checks out to Bob Creeley.

Creeley: I’ll take care of it.

Filreis: I can reserve my Williams questions. Who is it on the phone? Dave? Well, let’s pipe him in.

Creeley: Oh, Dave.

Filreis: Dave, can you hear us? Good morning.

David Gitin: Good morning.

Filreis: Where are you?

David: Monterey, California.

Filreis: Monterey, California.

Creeley: You lucky dog.

David: Great. I haven’t seen Bob in years. … Okay. I was listening last night, and in the poem “En Famille” there was a line “Has anything happened you will not forget” and I was curious — this line is a little bit circular and at the same time very opening, I think, for writing students, and I wanted to have you comment on that.

Creeley: You know, David, I guess that was some echo of not so much being didactic teacher but in some ways as much a question to myself as to whomever is reading or hearing it.

David: Of course that has opened up quite a lot.

Creeley: Well, what do you remember? What does one remember? What, my mother might say, what does one take away from this as information? What sticks? What stays in mind?

David: Yeah, the way you’ve worded it, it’s impossible to think of what you haven’t, what you’ve forgotten, right?

Creeley: Yeah. Dig it.

Filreis: There’s a recent poem of memory called “Given.” I don’t know if you are aware of it, it’s in Life and Death.

David: Yeah, I’ve got it.

Filreis: I wanted to ask Bob Creeley about it. The title “Given” strikes me as, among other things, referring to what is given, what is assumed, what is a priori, what is simply there. And in a way what happens in that poem is that Robert Creeley’s memories are so far ago — “who can throw a ball, who draw a face, who knows how” — that in a way, at a certain point in age, the memory of an experience becomes almost a priori, becomes a given since its so far ago.

Creeley [reads]:

Can you recall

distances, odors,

how far from the one

to the other, stalls

for the cows,

the hummocks one jumped to,

the lawn’s webs,

touch, taste of specific

doughnuts, cookies,

what a pimple was

and all such way

one’s skin was a place —

Touch, term, turn of curious fate.

Who can throw a ball,

who draw a face,

who knows how.

These were locating measures almost, not rules of thumb, but these were locating circumstances I recall from being a kid. This was the information. Has something happened you will not forget? What, thus, stays in mind in that relation would be those factors, those things. Not only those first time circumstances but these ways of measuring one’s apparent reality.

David: Well, that was a fascinating response, Bob.

Creeley: Well, take care, David. One day I’ll get there.

David: Well, that turn of curious fate is certainly interesting, of the measure, as you say, of those last three lines.

Creeley: The wheel.

David: Well, thanks.

Creeley: David is a solid poet in his own right incidentally.

Filreis: How long has it been?

Creeley: We used to know each other, it seems to me, particularly in New Mexico. And then we saw each other occasionally on the west coast. He was living down the coast. I was living in Bolinas. He’s a very particular writer, poet.

Filreis: Why don’t we go to Bob Perelman in the room for a question.

Bob Perelman: I was just reading some of Pound and Eliot this morning —

Creeley: That for breakfast?

Perelman: Because I’m teaching that stuff. Yes, first I do the crossword puzzle, and then I read The Waste Land.

Filreis: Sort of the same thing?

Perelman: Usually there’s a few clues in each one that are the same. But I was struck again, and it’s been, for me, thirty years with those types of people. Thinking about make it new, innovation, and the insistence that the past, that literature forms an ideal order that is simultaneous and does away with time, but at the same time there is this passion for innovation and a kind of very competitive insistence on who is making it and who is not, who is making it new and who is pretending to make it new, and it really strikes me, having the last four or five times hearing you read, how your whole career starts out, I think, with Olson, that you two were as passionate about making it new as anybody on the planet in the late ’40s and early ’50s, which was completely crucial, and lately there are so many gestures in your work that —

Creeley: Make it old —

Perelman: Make it old, that really want to kind of modify that, not disavow it, but certainly let in what that excludes. It seems like a very interesting tension if you could talk about that.

Creeley: I think it’s this sense that now is time to put all the toys away and get ready for bed. It’s a sense of putting things back where you found them. Actually, it’s a curious wish not to become common. That’s very hard to do. The point is it’s too late. To become as transparent as possible, which would mean simply to really move into whatever argues the most familiar and the most common kinds of habit in the organization of the composition. That’s why I think I am attracted to hip-hop actually. It has a very particularizing personal situation of expression. I keep thinking of Paul Barman, and I was looking him [up] again on the web this morning: the nerdy from New Jersey, who has this light, classic white voice. So, that aspect of him is very much Paul Varman, but the incredible punning languages and reach to all this diverse information, some of it extraordinarily common, square, and others — Polish film directors, et cetera — being quite specialized. So, what I’m trying to do is find a voice, really, that has no rough edges. In that poem “En Famille,” for example, I’m using loop forms where I’m repeating rhymes at the end sometimes four or more times. Everything, as David pointed out, is returning, keeps coming back to itself. So, it isn’t that I’m hoping to delay the final moment or something, but kinds of edge, kinds of tension, kinds of pressure to singularize myself are literally fading out. I have no will for that character of resistance any longer.

I can get certainly as angered by Governor Bush’s disposition towards public health and taxes as I ever did, and outraged that 25 percent of his state has no health insurance, or that Medicaid is exceptionally difficult to apply for in Texas. That kind of information can still provoke real anger and certainly singular behavior, and collective, one hopes as well. For the poetry, at least, that I am composing, I want it to be — I’d love to have it melt into some general state of things. I think I begin to want more and more echoes like, “I wandered lonely as a cloud.” It’s not parody. When I was young, [my line] “she walks in beauty like a lake” [was] parody, you know, [of] Byron. “I wandered lonely as a cloud” is not parody. Ideally, Wordsworth could continue the poem as well as I could, so to speak. Maybe he will, who knows?

Filreis: Now back to Williams. Your initial response to Williams — according to something you said at Camden in December — was that what mattered to you in reading Williams, particularly The Wedge, was that the work was driven by anger. This is what, at least, Ron Silliman posted to the Buffalo poetics listserv afterwards. And then he went on to comment at how Williams had a huge impact on him as well, but it was a very different Williams. So, if anger is not quite operating as much, what’s your Williams now? How does Williams animate you now?

Creeley: Back to Ron’s point, that that wasn’t the Williams he read; he reads the later Williams.

Filreis: The Desert Music.

Creeley: Yeah. Which is not an unangry poem, so to speak. But it certainly isn’t nearly as angry as the poems he was writing in the ’30s or ’20s. Spring and All, for example. Or the “Descent of Winter,” or “March First.” Many of the early poems are really angry, and their emotional base is their revulsion and anger at the world he finds around him.

Filreis: So, now when you look back at Williams, how does it feel?

Creeley: Well, it feels very much like my own life. I, when young, felt a dismay, let’s put it, that such things as the Holocaust or the Second World War or the depression or many other factors in one’s real life — that these could be so unremarkable to the body politic, that it seemed not to matter. Through the agency of my terrific wife, I sent an article — I think it was called “Bush Goes Green” from The New York Times to this listserv that a friend of ours sends us, you know, Barbie dolls and things women have to do to protect themselves in parking lots, lots of actually useful information, but the list has had a certain smugness. So, I zapped out this Bush article — Texas is fiftieth in education, and so on — and instantly comes back a letter: “Don’t send any more of this to me. I’ll vote for Bush no matter what.” So, I was disappointed that one would vote for someone who commits to have his state have 25% of its population with no insurance, who would willfully do so, and fight to preserve that situation. I still feel anger in that way.

But again, back to the verse, think of the classic phrases humans make: X wants to make his peace with the world. The resistances of Lawrence’s, “the day of my interference is done,” the recoil outstrips the advance, et cetera. I remember one time, terrifically, I had the chance to ask Kenneth Burke at a communal meal we were all at up in Orono — there was a moment when I had him to myself, so to speak, and I asked him quickly: what advice would you have for someone as myself who is getting old? And he looked at me and said: Don’t boast. You won’t be able to back it up. Therefore, it isn’t “don’t get angry, don’t use anger as a primary emotion.” It’s extraordinarily hard to sustain. It always was incidentally.

Filreis: Heather [Starr] has some questions, Bob, from people out there who have been emailing.

Starr: We have a couple of different questions. Here’s one from Joe Massey. He says there seems to be a cuteness to the poetry being written today. Do you think young poets today lack a certain intensity, and, if so, why?

Creeley: Joe, that’s too loaded a question. Let’s keep peace and quiet. The last thing in the world I would presume to do is pass judgment on such a wide spectrum of poetry, e.g. poetry written by the young. Some young persons write a poetry that’s quite decorous and pleasant in that sense. Others write a more invigorated and more argumentative charactered verse. The point is there are many, many ranges of poetry at the moment. I think again, Paul Barman’s one aspect. There’s an anthology momently to be published by St. Martin’s press called Heights of the Marvellous, edited by Todd Colby, which has a fascinating range and impact of characteristic present poets in New York, and I think that’s not pretty at all. I mean, some of it is terrifying.

Again, I don’t think you can generalize to that extent and say it’s all this way or that. I think poets, if anything, are concerned with career more than my generation was. Not long before his death, Bill Bronkin called for a conversation vis-a-vis a festival in England that he hadn’t been able to be at, and I was there. He had sent a tape that was played there, and he was asking how did it work out. So, I was able to tell him it was very dear and pleasant. Then he was talking about poetry more generally, and what he said was, “I don’t have a sense of having had a career in poetry. Not that I felt frustrated, but I never thought of having a career.” And I never thought of having a career either. I mean, no one of my generation set out to have a career in poetry. No one. I don’t know what we thought we were doing, but it wasn’t that. Career was just not what seemed to be the appropriate circumstance for that activity. What would the career apply to? You could have a career in street cleaning or something, but a career in poetry would have no pertinence.

Filreis: Bob, we have a question from Stuart Curran.

Stuart Curran: Speaking of the dangers of generalization, what was the occasion of which you first said, or did say, that form is simply an expression of content? Did you expect it to become a mantra for a generation? And do you still believe it given how conspicuous rhymes are in your late poetry?

Creeley: I remember feeling form is never more than an expression of content. That is, whatever form is the case is effectually accomplished or proposed or shaped by the content. In other words, you have some circumstance like dropping water on the floor: it takes the shape according to the character of the water on the floor, the water being the content. Apparently, in the I-Ching, there’s an instance of the beard on the face being shaped by the contours of the chin. It’s a very familiar proposal, but again like any didacticism, it can be converted to the absolute opposite of that. You can say content is never more than an expression of form. That would make equal sense, that the form it has provides, defines the content.

Perelman: I’m thinking when you wrote that, you and Olson jointly wrote that, there was the hegemony of people like Wilbur and what was celebrated, sonnets and rhyming stuff. You wanted to say no, it doesn’t have to rhyme, you write what you write.

Creeley: Exactly. Bob makes a very useful point that in the context in which that statement was made, and it was made as part of a letter. It wasn’t made as a great didactic premise. We were faced with such an habituation of authorities of form, that is, the whole imagination of the poem bien faites. A poem had to have these formal circumstances or else it was not a poem. I am trying to remember the very pleasant man who first told me the story of a friend of his reading at some midwestern college, and after he’s given a reading he invites questions, and the first question is that next to the last poem you read, was that a real poem or did you just make it up yourself? That was a statement from about 1950. So, in other words, there were real poems that conformed and were defined by the formal agencies that poems were supposed to have, and there were other poems that “one just made up one’s self.” That was our frustration. That poets of our absolute respects — such as Williams and to some extent Pound also, and certainly Zukofsky — were determined they were not poets because they didn’t show mastery of this or that form. When Hugh Kenner, for example, in an article remarkably in The National Review, qualifies Zukofsky as the superior prosodist in relation to W. H. Auden, that’s one of the great heroic moments of our time.

Filreis: In The National Review, too?

Creeley: Yeah.

Ron Silliman: One of the questions that occurs to me is that among your peers, your immediate generation, you seem to have been willing to have gone in new directions more self-evidently than others. When I think of a book such as Words, or of Pieces, or even of Mabel, those are all works that largely have very few precedents formally. You might be able to find some for Mabel in Stein, you might be able to find some for Words in some of Zukofsky, but, by and large, you’ve been willing to write poems that didn’t look like poems that existed previously, more so than others. I am curious about how you gave yourself permission for that.

Creeley: Well, Ron, in some ways it was a curious desperation. Remember, as you would well know, my terrific peers were all engaged variously with long poems. And they had visions. They had dreams; they could remember their dreams. And I felt like the tag-along kid or the person who was certainly well-treated by these dear friends, but who couldn’t himself or herself manage to get that diversity, that variety or that periodicity into his or her poetry. So, in that sense that’s really what the provocation was. I was moving with, say, words to try to break habits of completion, habits of imagined perfectness, of perfection performed, thoroughly realized. I was trying to let my self be not casual necessarily, but far more inconclusive. I remember one of the dear phrases of my youth would be [in] works such as Joyce’s, that always ended with “to be continued.” So, one was always reading tacitly a piece of, rather than an all of. And Pieces was, in one sense, a very didactic and, hence, simple frame, you know, one thing after another. I love that. One day after another, perfect. They all fit. I’ve always felt myself in the company of, gosh, not Little John, but Will Scarlet, thinking of Robin Hood. I was not Tom Sawyer, not Huckleberry Finn, God bless him, but the person who is there not simply to augment, to hold the armor or something, who is not along for the ride, but who has a partial, less-heroic fun.

Thinking of Allen [Ginsberg], for example, who had this immense ability to engage a public fact and condition a response; and Charles [Olson] had this incredible ability to cause a mythology, mythologize; Duncan was one of the great sort of storytellers and also, again, mythicizers. I remember his qualification of Language poetry way back then — “I must say,” he said, “you were an exception because you had a sense of humor” — was what he thought was the lack of story, the lack of narrative, not so much the lack of narrative in the formal sense of an agency of story-telling, the story inherent in the facts of a life; in relation to them, I was always doing what I thought I could do. So, the permission was really in the act, rather than in the disposition.

Filreis: Ron, do you want to follow up?

Silliman: No. I mean, I had thoughts of envisioning Olson as Friar Tuck in there, but I don’t think that’s a question.

Filreis: Thanks, Ron. We have a question from J.C. back here.

J. C. Todd: To follow up from what you’ve been talking about, I have a curiosity about where Denise Levertov fits in all this. I know that her first poems published in the States were almost solely published in Origin, and that there was a way in which that freshness you speak about is apparent in her early voice. So, I wondered if you would comment a little bit how Denise, early Denise, fits into all this.

Creeley: I first knew Denise when she and Mitch Goodman had married. Mitch had been a classmate of mine at Harvard. He was in Adams House, and he was a year ahead of me, but we were friends, we knew each other. We worked for The Crimson, et cetera. He was to come back to New York, and the various gang realized that he was coming back with this extraordinary English person, a person whom Rexroth referred to as Dante’s Beatrice reincarnate, which was a pretty heavy label.

So we scurried about — I was living up in New Hampshire — and went down with our truck to visit, and thus met Denise. Now, I was fascinated. She was intense, handsome, an extraordinary person. And so, they came up to visit us in New Hampshire. We talked a good deal. She had her first book, The Double Image, and it had been in some ways written in the style of that period in England: heartfelt and compassionate, but, nonetheless, in prosody, quite drab and generalizing. The classic pronoun is “we.” The shirts on the line are pretty much anybody’s, however moving. Workmen’s shirts. The particularizing isn’t there yet. She’s using a kind of blank verse line which is very steady on. Her company, then, as a peer, is a poet Dannie Abse, who becomes a doctor and who I believe is still alive. But if you look at the parallel — not careers, but the parallel circumstances of these poets, the responses at that point are variously Alex Comfort and Charles Ray Gardner who published in the Poetry Quarterly.

So, it’s a classic tacitly drab poetry that she’s engaged with. She comes to live in New York. This is West 15thStreet, just off 7th Avenue. She’s caught in that extraordinary vigor, and that shifted her life very immediately. I don’t introduce her personally to Williams, but I think I certainly remember intensely talking with her about him. We had become neighbors and friends. They go over to live in Prix Ricard, just north of Aix, and we lose our house in New Hampshire and trail after them to France, and live in a house that they obtain for us in a little town called Font Rouge. So, we can walk from one town to the other very comfortably, and I used to go and sit and talk with her in the mornings about prosody and all that. We spent a lot of time on what we thought about Williams’s line, how he managed it, what it actually accomplished. This was a crucial and real time for both of us. I remember giving her Williams’s address. And he wrote: there’s a poet who writes me swearing devotion, et cetera, et cetera. This was Denise, and they had become crucial and defining friends, both of them, one for the other.

Filreis: We have a question right here.

Speaker: Robert Bly, in his introductory essay to The Best American Poetry of 1999, talked about heat in poetry and heat in words, and suggests that technology and the Internet is taking the heat away from words that we get in these chat rooms, that they are losing heat that way. I wanted to see how you felt about that: do you agree with him somewhat, or disagree with him completely?

Creeley: It’s true that saying things can have enhanced or intensified occasion by being restricted. Bleakly, but interestingly, I remember watching a television documentary on Russian writers who had come to the United States in exile. One of them was being questioned and asked the obvious question: How is it now to live in the country where what you have to write or say is not facing the censorship you had in Russia? And he’s saying: Well, it’s curious, in this country one can publish everything, but no one particularly reads it. In Russia, he at least knew that one person was reading every word he wrote. The point being that poetry in Russia had immense social power. It was really incredible. I remember reading in what’s now Saint Petersburg, or what had been Saint Petersburg, Leningrad now, Saint Petersburg again. I read there, and it was on a Saturday afternoon off the Nesky Prospekt in this old government building, and there was an incredible audience. Notes began to be handed forward before I had even read two or three poems. There was a immense interest in both me as an American and as a poet. But the point is, the Internet, in so far that it makes distribution of poetry so extraordinarily simple — I mean, eight million hits on a poetry site such as the one at Buffalo almost can’t be imagined. Ginsberg at the height of his circumstances sold around two million copies, which is a lot. But eight million, from ninety countries — that’s pretty impressive.

So the point is: is that bad? That’s the question. Of course, it changes, redetermines the situation of poetry, but having grown up with the disposition of Dylan Thomas’s “In my craft or sullen art” practiced in the moon’s rage, the lovers having a great old time, and here I sit in this little dingy attic, the imagination that poetry is somehow enhanced by isolation and meagerness of prospect, I really don’t agree with that. And I think that the Internet is really one of the absolute opportunities of poetry.

Filreis: And the Internet also makes it possible for us to host here conversation between Robert Creeley and Marjorie Perloff who is on the phone. Marjorie?

Marjorie Perloff: Al?

Filreis: Good morning. How are you?

Perloff: I’m fine. Hi Bob.

Creeley: Hi.

Perloff: I have a question for you that I’ve wanted to ask you for a long time, and that’s in regards to love poetry.You’re obviously one of the great love poets of the time. Why do you think there is so little love — what one can even call love poetry — being written now or for the last few decades actually?

Creeley: The anthology I mentioned, The Heights of the Marvellous — what’s fascinating in that collection of poets [is] the ways in which they qualify or address other human beings as being there. They are not prurient or attacking, but they really register the other person in every conceivable scale. It’s extraordinary how reifying that poetry is of the other person. I remember a piece that Octavio Paz did in which he expresses his dismay that love has become only singularly a sexual identification.He feels that love in the more extensive manner is pretty much disregarded.

Perloff: Yes.

Creeley: My son Will was home on the weekend, and he’s now in his first year at NYU. And Will was saying he feels that we as a family are all a piece, as though we were all various parts of a body. I was very moved by that. And felt perhaps it’s the way love, not so much has been bowdlerized, but needs to be —

Perloff: Media-ized.

Creeley: Exactly. I think of John Wieners [?], whom I considered truly a great love poet.

Perloff: Yeah.

Creeley: And Denise. Back to things like losing track, or of the ache of marriage, wherein love not only got a definition, but got a substance that was absolutely remarkable. Ginsberg was a great love poet.

Perloff: Well, it seems there are more gay poets probably writing love poetry, because I remember Allen Ginsberg once said to me that, well, there’s a lot of sublimation involved, and that’s why we write love poetry.

Creeley: One thing, Marjorie, one can’t get away with “My love is like a red, red rose” anymore.

Perloff: And Gertrude Stein is a really great love poet, now, that we can turn to.

Filreis: What do you think of Bob’s referring to Will’s weekend conversation about the family, for Bob, enlarging love beyond what we normally think of love poetry or what one would think of the love poetry from the early work of Robert Creeley —

Perloff: Yes?

Filreis: This is an enlargementbeyond Eros.

Perloff: I think Bob is unique in that he has always dealt with this, without ever being soupy about it at all, which is the great thing in his poetry. That it really isn’t sentimental, but dealing with human relationships and dealing with the importance of that, which is something that in most people’s poetry has really been cut out in curious ways, and is a lack in some ways, that people are terribly reticent about putting themselves on the line.

Filreis: Why are they reticent?

Perloff: Why?Well I think it is, I think Jed Rasula describes it well in Poetry’s Voice-Over, in his book, which is that the media supplies us with so many fake emotional things and the language of it, that it’s almost impossible to talk about it without dealing with it in that way.I mean, look at the whole Elian Gonzalez thing. What I’ve noticed that I think is very interesting [is] how awful the vocabulary is with everybody … saying quote unquote, well, he has a loving father. How do we know if his father is loving? We don’t really know anything. I mean, maybe he is. Maybe he isn’t. What is a loving father? But when the vocabulary gets that debased, which it has, it’s very hard to do certain things.And now I think Bob has always managed to do it — like this one, like that one, like this one, like that one — by doing it so indirectly and delicately that one can catch an emotion that is a real emotion instead of these clichés. But I think the whole vocabulary of love today, or of any kind of relationship, is so clichéd, and they say you can see it right this week in this whole ridiculous television soap opera.

Filreis: Bob, do you want to comment on this?

Creeley: Well, I was thinking I was just in Buffalo on business this last weekend. Someone turned to me and brought up again my deathless poem “For love I would split open.” I remember with what confidence I wrote that as a young man, this sort of deathless pledge to love. It took a woman, like they say, to say you know that awful violent poem you wrote about splitting someone’s head open. I guess, again, I didn’t depend upon naïveté or stupidity, but it certainly helped me a great deal.

Filreis: As Bob prepared to read the poem in the family book collaboration with Elsa Dorfman last night — he did it boldly — he said it sort of takes guts to write a poem like this, with the risks of sentimentality and so forth. And by introducing it in that way, the hundred people in the Writers House all took a gasp. You know, how dare he let loose and hard. And as the rhymes started to pour on us like rain at the end, and you gave up reading it, saying, I can’t go on, maybe out of tiredness, maybe worrying you were risking sentimentality, I don’t know.

Creeley: I don’t worry about it.

Filreis: Good for you. Well, we have a question from David Skeel, who’s on the law faculty. I don’t know if it’s a legal question, but here we go.

David Skeel: You mentioned back at the beginning of the conversation that your early work focused a lot on the register of the text and that others were focusing on that. I wonder if you can elaborate on that.

Creeley: Well, we were thinking how can the text be as particular as, say, a score in music. The score in music, incidentally, was undergoing very extraordinary modifications and changes as well, thinking of Cage and other composers of that moment. As poets, I think we felt one of our responsibilities, and equally one of our possibilities, was being able to make a text that would provide a means for reading with the least distortion of our own purposes or intents. Anyone who thinks he or she can control the effects of what they are doing in that particular circumstance — it’s a distraction, it’s foolish. There’s no way I could ever fathom or surmise that which would give any artist an ability to understand or to forecast or even to anticipate in any real way what the effects of his or her acts would really be. Lorca being the primary instance. So, that isn’t really the question, it’s wanting what one has as [an] initiating condition of saying something to be somehow possible. I was listening to Jerome McGann, for example, at a Duncan Conference at Buffalo a couple of years ago, making the equally apt point that no text is ever resolved. It’s not possible. Its variants are insistently and forever the condition. But nonetheless, we wanted to cut through what we thought was this aestheticizing blur of habit. I remember Zukofsky telling me how long and what terrific, almost heroic, enterprise it proves, and his respect for Cummings was thus very large, to get rid of the capitals at the beginnings of lines. Now it’s kind of jazzy to bring them back. It gives a curious effect to return them.

Those shifts, which seem so modest in typographical condition, had really substantial circumstances. Again, thinking of Olson very particularly, to center or off-center three or four words themselves in relation to one another in a very particularized way is to really change entirely the imagination of a page. Or Kerouac’s writing on newspaper roll, newsprint. All of those things were very real changes in the imagination of what one was doing, what were his interests in doing it in the sense, what was one trying to do with a text. There were so many factors that entered the imagination that this was something sound. Duncan, for example, felt that no text or poem was thus complete until someone read it.

Filreis: Bob, we have a question from Andrew Zitcer here.

Andrew Zitcer: Just to switch gears a little bit, in your poem “In London,” and I think about three times in last night’s presentation, you referred to Bob Dylan, who was certainly active during the time when a lot of this was written in the anthologies, and I wonder if you can speak a little bit about his role.

Creeley: I thought he was a master of rhythmic patterns. I thought, too, that he was able to use not simply idiomatic, or a loose sense of common words, but I was fascinated by his clarity of language. I loved it in a person like Hank Williams. I am trying to remember the name of the writer, Francis somebody-or-other, who had an article in The Atlantic Monthly in the last year or so, in which he’s talking about Dylan, a recording from the early ’60s that was released, a concert, and he quotes from this poem of mine. Then he says something that really pleased me: he said that I used backbeat, as he calls it, which I certainly do. As does Dylan. It means coming in on the unemphasized stress, beat, coming in, variously, with Charlie Parker, coming in late, as they say. You get a very curious syncopation from doing that. I thought that Dylan was a master in terms of his ear and his ability with the rhythmic patterns. You remember, perhaps, there was an article in Rolling Stone in the early ’60s called “The Poet’s Poet” by Mike McClure, which gave Dylan an absolute respect, and was an instance of the way we all variously felt about him. Because, again, we were trying to break down clichés of enclosure, just that Dylan wasn’t a poet, in the sense of the pop music. I felt that among other reasons why in this last day I put such emphasis on a poet — or what I would call a poet — as Paul Barman. I get so bored by discretions that want to put that character of writing apart from the “real poetry,” which, to begin again, to define poetry as an activity dominated by subject, by discretions of rhetoric, so on and so forth — which to me are really, if not malevolent overtly, certainly of no use to anyone.

Filreis: A question here from Carolyn Jacobson, and then we’re going to take a question that’s been emailed to Heather. Then we’re going to wrap up.

Carolyn Jacobson: I’m going back to the idea of register, and the importance of place and rhythm of voice. I was interested to hear you talk about paying attention and being interested in whether Williams stopped at the end of lines or not, and that made me wonder if you ever hear other people read your poetry? And it must be an interesting thing to feel like you can create your rhythms in your voice, and then have other people recreate that in their reading of your work. So, I’m also wondering what it’s like to hear people get your work wrong, if you’ve had instances of that, and what the effect of that is?

Creeley: Larry Bronfman was a friend of Paul Blackburn’s, and Larry’s uncle, I guess it was, had a substantial print shop that Paul worked at for a while. But in any case, Larry Bronfman was very interested by my poetry. This was back in the early ’50s, and I remember he drove down to Black Mountain with me, and I had a modest reading there, and I remember he was aghast at the way I read my poems. He said, you know, it frankly destroyed his interest in my poetry. He said he would never read my poems like that. Another dear friend, a much dearer friend actually, was Bill Bronk, who said “why do you read your poems in that manner?” Well, that’s the way I wrote them. He said, God, you sound like you’re dying up there. The strangling and all this stuff.

Filreis: He should hear the Libretto do it.

Creeley: Then I remember, once, so terrific, one time, I was reading at MIT, and I remember then came the end of the reading, and I had invited questions, and someone says I don’t know anything about you, and I don’t know anything about poetry either, but I was just walking by the back of the room, and I heard you reading, and I said it’s a very odd way of reading, so I decided just to stop and listen a bit. And so he did, and he said, I’m just curious: is that on the page? How do you get that kind of weird reading out of it? So, I invited him to come forward and simply read the poems as they were printed, and the only advice I would give him, the only thing I would ask of him was that he stop briefly at the end of each line. And so he did. He read it beautifully. I mean, it sounded precisely the way I wanted it to be. So, I guess that was my reassurance that what I was writing was translatable. And the people I had most difficulty with were those who both expectably and legitimately were overreading or overwriting with interests of their own. It wasn’t that they were good guys or bad guys. But again, if, and as, the prosody holds, it will take care of that. It will play it still, so to speak, through the override of an impulse.

Filreis: We have a last question from Kerry Sherin who is the director of the Writers House and who is writing a book about Eliot. Kerry.

Kerry Sherin: I love the way that dissertation becomes a book.

Filreis: Is it book-length? Then it’s a book. Just make a .pdf file of it, and it’s a book.

Sherin: Bob, I have a quick question for you about love poetry. I love Marjorie Perloff’s question about love poetry, and it made me think about who you might count as influences in the poetic tradition, or even in other traditions, in other media that you think of as influences. And I am especially interested, I guess, [in] prosodic influences, especially since that’s been something that you’ve been talking about — but I’m wondering, usually you talk about Williams.

Creeley: Back to my generation, talking about my generation, we, all of us, read the metaphysicals. I don’t think there was any one of us that didn’t read the metaphysicals. It ranged from respects there were immediately sort of located Donne, but then went variously to Herbert or Crashaw or to other qualifications of Vaughan, for example. I remember Duncan, we were talking once about poets who we would love to do a selected edition of, and Robert’s real pleasure would be to do an edition of Vaughan, Henry Vaughan. But when I think of the core poets to love, in particular, I loved Herrick, as Zukofsky did. I find Herrick is a great poet, and of this peculiarly small, domestic, extraordinary reality.

Then, too, there were prose writers, D. H. Lawrence, but also Stendahl, Dostoevsky, et cetera. At that point, love becomes comingled, as they say, with emotions, with passions and relationships of people. Whitman I came to late, but him certainly. And Emily Dickinson endlessly. Coleridge, I loved Coleridge. He stayed most faithful, to my mind, of the poets that I think of who locate human feelings in ways that I certainly know. I mean “The Paint of Sleep,” I think, is to be beloved. I remember one time Ed Dorn said of Allen Ginsberg: all he wants to do is be loved. And I thought of great old S. T.: to be beloved is all I need, and whom I love, I love indeed.

Filreis: Bob, I was hoping we could conclude by having you read any poem at all and just making a brief comment on it.

He reaches for Life and Death of 1998. Anything at all, and comment by way of conclusion. That would be great.

Creeley: That’s not so easy. I’ll try and find something that’s quick and particular.

“A Valentine for Pen,” speaking of love.

[Reads “A Valentine for Pen.”]

You know it was a valentine. It wanted to say, simply, I love, I love being here, I love you.

I remember one time when Will was very young, we’d gone up, myself and Hannah and Will, and a pleasant younger woman who was a kind of classic nanny when my wife was studying at Cornell — and in any case we got to Maine early, and I remember Will’s a bit disgruntled, and I ask him what’s wrong, and he said without mom, there’s no love in the house. And that was a yes, my boy. And that’s it, what’s more to say?

Filreis: It’s the same word home at the end of the poem “Goodbye.”

Creeley: It will break your heart.