An interview with curator Kaegan Sparks

KG: Your work as a curator seems to happen in and around interdisciplinary nexii. Maybe I see it that way because of my sense that in the contemporary moment we’re seeing increasingly blurred genre boundaries. I wanted to talk to you mainly to get a sense of whether or not you think of your work as inter-generic curating. You’ve curated talks, films, live drawing performances, sometimes all in the same event; you curated for a couple of years for the Segue Poetry Series; within your art curation there have been books, art with language and writing as a major feature …

KS: Over the past few years I’ve produced exhibitions and events under a wide spectrum of parameters — from simple one-artist exhibitions (or two-poet readings) to collaborative models that I formulate and solicit participation for, to freelance curating where the work is preselected and I’m expected to synthesize, manage, and optimize the presentation. Each particular matrix of strictures and priorities has been productive and hugely rewarding for me, in terms of flexing my muscles as a facilitator of discourse in different contexts. So beyond focusing on formal variety among the cultural material I work with, I’m more interested in talking about the inter-structural status of my organizing itself — especially per curated events in a museum context, which for me have a bearing somewhere between poetry reading and exhibition.

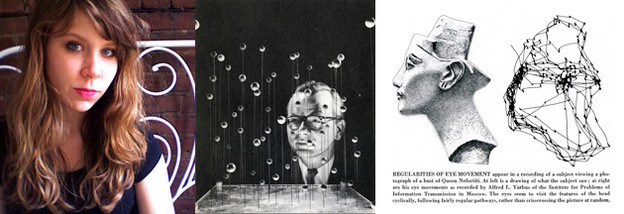

Drafts, a program series I’m organizing at The Drawing Center, is conceived around a network of collaborations—the image archive of the Reanimation Library (comprising e.g. instruction manuals, hobbyist books, and general interest encyclopedias mostly printed between the 1950s and 1970s) precipitates each program, and selections from it evolve among the programs themselves, as an inherited (if unwieldy) line of thinking. I invite a sequence of cultural producers to “revise” or resituate an image selected for the previous program among a new set of images, and each set forms the basis for a program of responses from a variety of creative practitioners.

KG: Are there particular challenges or benefits to interstructural organizing?

The apparatus of Drafts, for example, tries to circumvent my own one-off arbitrating and instead foster a collaborative and somewhat self-generative engine, where connections depend on a framework beyond simply my tastes and expectations. I’ve yielded some control over the direction of the series, so that holistically it operates more like a conversation and less like discrete units. This to me is a crucial break from, or compromise between, the conventional profiles of event and exhibition (the event is contained, and yet to some degree unpredictable; the exhibition is micromanaged, but has space and duration). Drafts has a framework and a “narrative,” like an exhibition, and it is ongoing, though staggered. In fact, the intermittency is really ideal — like neither one-night event nor traditional exhibition, the series has the opportunity to adapt per reactions to each hand played; comments and suggestions from perspectives I hadn’t thought to consult really do actively shape the programs to come.

If not specifically intended for and attended to, though, the sort of roll-with-the-punches nature of organizing events can prove inhibiting. One reason I’ve made the purview of Drafts explicitly broad is that I was frustrated with curating poetry readings. Specifically, those with a template of two readers that organizers must file in tandem to fit a rigid schedule (not to name any names). Every satisfying event is just a perfect storm, but I found it increasingly difficult to produce readings that resonated when aesthetic choices fell sway to logistics. Another ingrained challenge to ‘syncing’ readers in a poetry context is that the protocol necessitates inviting a pair based on a perceived aesthetic affinity — which of course derives from some subjective idea of a writer’s work, which is often too specific or too cumulative (and thus reductive) — and as many times as not poets read something that deviates from that caricature (not to mention your introduction!). This can disrupt the chemistry — though not always unproductively — as curatorial oversight is fairly limited.

KG: In November of 2012 you curated an exhibition called Prolonged Exposure for an organization called Recession Art at the Invisible Dog Art Center in Brooklyn. The call for work you wrote centered around boredom. First, why boredom? Second, your curation seemed focused on the multivalent object, so I saw the inter-generic thing happening there too. Could you address some of the work from that show that challenges genre, or called upon your interstructural skills?

KS: In terms of my practice, the topic the show hovered around was less significant to me than the parameters I had to work with — this was an open-call exhibition (meaning we solicited submissions publicly) and Recession Art is focused on featuring affordable art for aspiring collectors, so there was a market-based factor that really affected the selection. The price point was supposed to be under $1,000 and any inclusion of video and new media was a compromise (that said, I did manage to show a lot of video). The open call in particular was really challenging to work with, in that I'm totally wary of prescribing a thematic assemblage top-down — here the topic could not arise from a perceived conversation among works; instead it had to precede it and call it into being. So I formulated the call as more of a provocation than anything else and let the project and its concept evolve from there. Notions of boredom, idleness, and restlessness are both critically interesting to me as charged or ambivalent, non-cathartic affects (I’ve been thinking a lot about Sianne Ngai, and had just finished her book Ugly Feelings at the time), and are also simply and universally applicable. One of the most successful elements was actually the programming that came out of it — in particular a program of films and poetic performance I co-organized with Eddie Hopely.

KG: I find it interesting that your beginnings as a curator happened in a literary — mostly poetry — venue, the Kelly Writers House. Do you think this created a special opportunity or made more obvious the choice to do inter-generic curating and inter-structural organizing?

KS: Certainly the literary aegis there was formative for me in all sorts of ways as my tastes developed — and much of my initial access to contemporary art was via writing at Penn, particularly per Kenny Goldsmith’s lead. In terms of having a foot in both worlds, he’s a prime example, and facilitated many relationships at that threshold that are very important to me: artist Erica Baum, for example, whose work I exhibited at Penn and with whom I maintain a working relationship.

At The Drawing Center, I’m something of a poetry-world emissary. My boss studied at UCSD and hung around West Coast Language poets during his undergraduate years, but his attention has since veered — I’m the only one there who's actively invested in it. Consequently I find the performance work I’m commissioning for Drafts to be poetics-bent. At KWH Art (now Brodsky Gallery, at the Writers House) the reverse was true, and in that arena the visual work I exhibited was often language-based, following the inclination of the institution, and also my own interests at the time. Besides Erica’s show, another example which you mentioned is the exhibition I organized in 2008 around Darren Wershler-Henry’s The Tapeworm Foundry, commissioning realized artworks from his pastiched instructions.

KG: Maybe we can end with a little musing about the future. What do you see coming in the future of curatorial practice? And maybe you can offer us a glimpse of a future, or even a dream curation of your own?

KS: I’m really beginning to focus on curating events, not as subsidiaries to shows, but as creative systems in and of themselves. A big influence for Drafts was Alex Klein’s amazing Excursus project at ICA Philadelphia — she has a really compelling perspective on what programs can do, the type of contrapuntal dialogue or constructive interference they can provide to exhibition-based environments. I do think it’s an alluring frontier these days; more and more curators are taking the possibilities of ‘ephemeral’ programming more seriously.

To critically different ends than the minutely tuned, and often protracted course of preparing an exhibition in most museum settings, I find time-based interactive frameworks often accommodate a more constructive exchange, not only through facilitating real-time conversations among different publics, but also precisely because of their mutability and susceptibility to disruption. The conceptual grounds of Drafts tease out, on a content-level, the structural conditions particular to the event as platform (of risk, of digression, of surfing — what Claire Bishop recently called the twenty-first-century derive, or “the logic of our dominant social field, the Internet”). It also registers a similar valence in the activity of drawing, or drafting, as a conjectural operation, a testing ground for caprice and revision. Of course, this formal analogy could be extended to writing — how shaping an event or confluence of voices that shift relates to the act of writing, and editing. This was a purposeful ambivalence.

A couple of triggers (or harmonics) for this sort of model are Alexandre Singh’s current exhibition at The Drawing Center, based on imagined tangents and corollaries to interviews he conducted, and the idea of “rhapsodic” conversation, replete with daydreamed cul-de-sacs, and Blanchot’s idea (borrowed from Valery) of conversation on a Riemann surface. The latter is a spatial metaphor for dialogue alternative to a cumulative, linear progression. Each speaker develops thoughts on multiple sheets of paper asynchronously to the conversation itself, following their projection of where the exchange will go. And yet because one can never accurately anticipate her interlocutor’s reaction, which will defer and detour where she thought she was going, many unspoken digressions remain embedded in a conversation. (For more of my rambling on this, see my book I Want So Much To Tell You, forthcoming from bas-books). I wanted to give voice to as many digressions as possible with Drafts, from the image selection to the events to the addenda on The Drawing Center’s blog.

Drafts: Phase II will take place on March 12, 2013.

Gossip or history