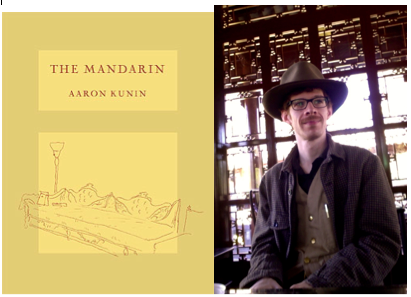

A conversation with Aaron Kunin

The poet's novel

Laynie Browne: Recently a show at the Morgan Library in New York City celebrated the 1913 publication of the first of the seven volumes of Swan’s Way. Here one could see some of Proust’s original handwritten manuscripts and notebooks, some of which have never left Paris. In one notebook, considering his book in progress he writes: “Should it be a novel, a philosophical essay, am I a novelist?”

In your novel The Mandarin, the question is potently raised in various ways, who is a novelist? What is a novel? I wonder if you could comment on this. Do you think of yourself as a poet and novelist? Are the categories important or useful to you? When you set out to write The Mandarin, what were some of your initial impulses or inspirations for the project? Do you recall what turned you toward prose? Were you interested in questioning any conventional notions of the novel?

Aaron Kunin: Isn’t it strange that Proust, who is definitely a novelist, asks himself, “Am I a novelist?” If he doesn’t know, how can anyone be sure?

When I started writing The Mandarin, I was curious about the difference between speech and writing, and the funny thing that happens when you represent writing as speech. I also wanted to write about food and sleep, and to put everything about Minneapolis in it.

The novel doesn’t seem like an exclusive genre to me. Woolf says that the novel has no special formal conventions, and novelists as different as Austen and Stein say the same thing. Stein says that the novel can include any sort of language or information; it is “everything.” A novel can include philosophical inquiry, journalism, poetry. It can be one hundred percent poetry — a poem, such as Eugene Onegin. If some of today's novels seem more conventional or exclusive, that is just because the novelists are not taking advantage of all the things that can go into a novel.

The novel doesn’t seem like an exclusive genre to me. Woolf says that the novel has no special formal conventions, and novelists as different as Austen and Stein say the same thing. Stein says that the novel can include any sort of language or information; it is “everything.” A novel can include philosophical inquiry, journalism, poetry. It can be one hundred percent poetry — a poem, such as Eugene Onegin. If some of today's novels seem more conventional or exclusive, that is just because the novelists are not taking advantage of all the things that can go into a novel.

There are some conventional ways of talking about novels that don't interest me. I have never liked the idea of free indirect discourse. I have never understood the idea of the unreliable narrator. And I don't respond to plot at all — I can’t seem to keep plots in my head.

Browne: In The Mandarin I get the sense that you are also saying a novel can be ephemeral. A novel can be written on a napkin in a very short time. (am I remembering that part correctly?) So that seems to fit with this notion that the novel is not an exclusive genre. I’m interested in this statement that the novel is “everything.” Sometimes I want to say that about any form to see how far one can go — for instance, a sonnet or a letter can contain everything. The poet's novel I think, if it is possible to generalize about so varied a form, wants know how much “everything” it can include, and also how much “nothing.” Can a novel be a short utterance or scrawl, a phrase whispered to a companion at table? Can it have no characters, no plot, no location? Well, obviously, yes, if the poet says so. So you’ve said you aren’t interested in these conventions such as plot, but what aspects of poet's novels do interest you the most?

Kunin: It’s true, I don’t respond to plot. I used to think that nobody responded to plot, but I was wrong about that. Wilkie Collins showed me that I was wrong. People kept telling me how great Collins’s novels were, and I kept trying to read them. I read four of them! And they bored me to tears. The Woman in White, The Moonstone — they are supposed to be fascinating and atmospheric, but they are all plot. Maybe not one hundred percent plot, but ninety percent. So there is living proof that I don't respond to plot, and that some people do, because the readers who love Collins have to love plot. There's nothing else in him to love.

It’s interesting that some people love plot, because plot is an abstraction, a diagram of causation. One thing happens so that another thing can happen, so that another thing can happen, and so on. And if the plot is complicated enough, everything that happens is a surprise — you saw where it came from, but you still didn't see it coming. Loving plot is like loving a rhyme scheme. Not the sound of the rhymes, but the diagram. Interesting, but not for me.

What I respond to in a novel are the compensations for putting up with plot. Style, voices, images, actions, characters. The descriptions of mountains and clouds in Anne Radcliffe’s novels, and her dippy poetry. The ersatz Jacobean epigraphs in Eliot’s novels. Everything about whales in Moby-Dick. Reading a novel by Trollope, I learn about church government, the decimal system, land reform. Rhetorical power. Clarissa kneeling to her mother. Jane Eyre rejecting Rochester, because, she says, she is his superior. All the scenes in James’s novels where one character influences or possesses another, or simply observes what is in another character's mind, and enjoys it.

A novel is made for these things. I don't think poets are necessarily better at them. Trollope is a genius at providing these kinds of satisfactions, and he has no interest in plot at all. Notice how he carefully destroys the possibility of narrative suspense in Barchester Towers (which is the purest pleasure I have ever experienced in the form of a novel). At the start, he informs you plainly that Archdeacon Grantly is never going to be bishop, and Eleanor Bold is going to marry Arabin rather than Slope or Stanhope. With that out of the way, Trollope can concentrate on more interesting topics — controversies over the apostolic succession, for example. No writer is better than Trollope at narrating momentary shifts in rhetorical power, how relationships and opinions can change in response to a sarcastic remark not even spoken aloud, but kept to oneself.

Browne: Do you have any favorite novels written by poets? Have any of these texts been formative to you as a writer? In what ways?

Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There. As in Proust, the whole thing takes place on the border between sleep and waking. Alice stands up suddenly, and tips over a jury box, and the jurors spill onto the floor of the courtroom. Then she's trying to corral the jurors back in their box, but as she does this she also sees herself returning a goldfish to the water in its bowl, and she confuses the two tasks, thinking that the jurors can't get oxygen outside of their box. A perfect anxiety dream. As in a musical comedy, sometimes the action ceases, and the characters recite poems and sing. The poems are masterpieces. Although they are parodies of other poems, they are always better than their sources. (Including “Jabberwocky,” which is a parody of Beowulf, and a much better poem than Beowulf.)

Then she's trying to corral the jurors back in their box, but as she does this she also sees herself returning a goldfish to the water in its bowl, and she confuses the two tasks, thinking that the jurors can't get oxygen outside of their box. A perfect anxiety dream. As in a musical comedy, sometimes the action ceases, and the characters recite poems and sing. The poems are masterpieces. Although they are parodies of other poems, they are always better than their sources. (Including “Jabberwocky,” which is a parody of Beowulf, and a much better poem than Beowulf.)

Two other novels by poets, Seeking Air by Barbara Guest and A form / of taking / it all by Rosmarie Waldrop, are important to me. What I take from them is related to what I take from Carroll's novels. Guest has a similar way of layering conscious and unconscious experiences on top of one another, and Waldrop does something similar with sources.

Lermontov, A Hero for Our Time. Each episode brings you closer to Pechorin, until you are finally inside Pechorin's head, and you understand him even less. He becomes more mysterious as you know him better.

I'm a fan of Leslie Scalapino's novels, particularly the ones in which Detective Grace Abe appears. Scalapino has an unusual facility with the English language. Whatever she wants to do, English will do it for her, without difficulty. I also like her treatment of sex. It's very repetitive, business as usual, basically the same three sex acts repeated over and over, in the same language. And somehow she makes it look completely Martian. The most vanilla sex becomes a compelling figure for human variety and possibility.

Browne: In The Mandarin I was really interested in the juxtaposition of the final section of the novel, and how in a way it rewrites or reveals what comes before, so when one finishes reading one is back at the beginning. This question of how one reads (and the tossing away of conventions in terms of the time in which a work is read or unfolds) occurs often in novels by poets. I'd love to hear your thoughts about this.

Browne: In The Mandarin I was really interested in the juxtaposition of the final section of the novel, and how in a way it rewrites or reveals what comes before, so when one finishes reading one is back at the beginning. This question of how one reads (and the tossing away of conventions in terms of the time in which a work is read or unfolds) occurs often in novels by poets. I'd love to hear your thoughts about this.

Kunin: I wanted to prove that the frame of the novel was really there. That the novel wasn't just people talking, which it mostly is, but that the talk was being narrated. The only way to do that seemed to be for the narrator to say something that was more than a dialogue tag. This happens twice, so you know it isn’t an accident. First he narrates the death of a centipede by newspaper, and then, at the end of the novel, he narrates his return to Minneapolis after a long absence.

Actually, it happens a third time. In one of the bakery episodes, the dialogue tags get a little bit longer, and include characteristic gestures: raising her hand in a kind of salute, arranging his hair, tearing the front of her coat, and so on. The characters are talking about relationships where one person speaks for another, and meanwhile they are having a separate conversation in their gestures, and Willy is narrating both conversations.

Does the last chapter rewrite what comes before? The same characters and situations appear in slightly different configurations, but that has been happening throughout the novel. The difference now is that you're getting only one voice, where before there were a few voices braided together. So it's more subjective. A reduction of what came before.

Ashbery said that he wanted the last word in A Nest of Ninnies to be an obscure word that readers would have to find in a dictionary. He wanted to send his readers directly from one book to another. I don’t usually see myself playing games like that.

Browne: I’m also curious about your statement that you were interested in representing writing as speech, as the end of your novel moves in a different direction. I’ve just started reading your new book, Grace Period, which is terrific, and I'm struck by how much of the writing is an inner conversation — insights that might not be spoken, or that have been removed or liberated from specific speech acts which might make them impossible. There is a great freedom in that disassociation. So how does a “novelist” get to that freedom while remaining within the particularities of dialogue? Maybe one doesn’t. Maybe that question isn't fair, as Grace Period is “Notebooks.” But I’m wondering how working with notebooks might inform the other writing you do. Do you write in notebooks or journals consistently still? Do you cull your notebooks for poetry or other projects?

Kunin: That’s a great description. Yes, Grace Period consists of selections from an inner conversation. I like that.

Some of the writing in my notebooks is planning and drafting for other projects. Most of the writing in my notebooks is just note-taking. Something interested me briefly when I wrote it down, and then interested me a second time, when I transcribed it.

So a lot of material in my notebooks didn’t end up in the book. Drafts for The Mandarin and other book projects. Practice writing in the vocabulary of The Sore Throat. Descriptions of people eating. (I do a lot of that — I'm not sure why it interests me, and I don't think readers would enjoy it.) There's a lot of personal material too, but usually this is generalized so it would be difficult to identify the person.

Anything you write tends to become personal. If I write a description of someone else, most readers will assume that I am describing myself. And they aren't making a mistake. It is about me; it is personal, because I wrote it.

Browne: Back to Proust. I especially love that quote because as you say, how can anyone be sure. Nobody can, which means that it might be useful to keep asking the question — and repeating the refrain that certainty can be problematic. Keith Waldrop once said to me that uncertainty is much more interesting than certainty. So is it possible that some of today's novels which seem more conventional think they must be certain? Is the “certain novelist” not a poet's novelist?

Kunin: I don't want to be pious about uncertainty. Some writers (I’m thinking of Andrew Maxwell and Johannes Göransson) are passionate advocates for didactic literature, and I have a lot of sympathy for their position, although it might be a stretch to call my writing didactic. There are moral maxims in Grace Period, but it isn't exactly a handbook for living.

Here is what I would say. If you are studying something, it is probably best to start from a place of uncertainty. You are more likely to make a discovery that way. But if you want to accomplish something, to make something and get it into the world, it probably helps to have some convictions. You have to be convinced of the value of your methods, at least, if not your conclusions.

The poet's novel