'Post-pleistocene relic world'

Alternative communities and writing, part 2

Naropa archive recording title: Alternative Communities and Writing

Date of recording: June 09, 2003

Panelists: Anne Waldman (Chair), Eleni Sikelianos, Peter Warshall, Ed Sanders, Marcella Durand, Robin Blaser.

Jaime Groetsema: In the article “The Lefevre-Sikelianos-Waldman Tree and the Imaginative Utopian Attempt,” Eleni Sikelianos writes, “A branch of the arbor vitae that Anne envisioned in San Francisco that very summer: the roots and branches of her history as a poet, even prior to her own birth, and the continuation of that lineage as passed on to others.” Is it necessary to think about community from an ecological point of view? If so, would our depicted world community be more populated with trees than our current ecological moment?

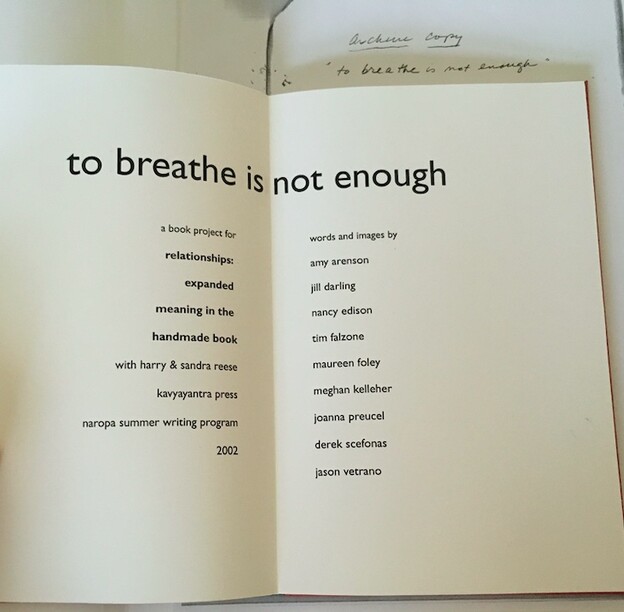

What would a Jack Kerouac School Summer Writing Program family tree look like? This, perhaps:

Photo by Jaime Groetsema. Courtesy of Naropa University Archives.

I took the above photograph of the summer Visiting Poetics Academy schedule from the 1970s. Every year would make a new branch of the family tree. I wonder about the students of W316 and the work they made alongside or under guidance of their teachers. Who was the scribe of this artifact? The typist, the typewriter, or the organizers of W316. Or, was it Anne Waldman, pushing forth the various configurations of poetry and lineage from before, to then, to now, to future?

I am reminded of an essay that I often turn to by G. Thomas Tanselle titled “The World as Archive,” where he says: “… treating archives merely as collections of words and numbers shows no awareness of the fact that every physical characteristic of every document is the trace left by a human action or a natural event in the past. The artifact has its own story to tell, one that can never be separated from what the words say or what the text as a whole signifies in social terms.”[1] What Tanselle points to reiterates the complexity of dystopia-in-utopia.

As a librarian working with archives, I wonder, too, about what and who preceeded me. Who held on to this document or moved it to the archive to be put in a folder, in a document box, and processed, and added it to a finding aid, and so then began the preservation process, so I could see it forty-plus years later, and in doing so, meeting Amanda and talking about archives and literature and writing this collaborative text. We, working with this material in our own time.

In the “Alternative Communities and Writing” panel from the SWP audio archive Peter Warshall’s notion of community comes from an environmental conservationist perspective. He says: “My sense of community starts in the Pleistocene, […] at that point, the distance between urban life and outdoor life was nonexistent, and the classic European, especially since Lévi-Strauss, division between nature and culture did not exist, and so, in a sense, my sense of community has always been to [get] nature into culture; culture into nature.” Similarly, a dualistic notion of the dystopian-in-utopian and utopian-in-dystopian, yet instead of suggesting that the emancipatory potential of writing is in the possibilities of art and imagination, Warshall seems to suggest that writing, if we are to take writing as the production of culture, must abide by both agenda and timeliness, and therefore culture must be concerned with the issues of the writing it produces.

Amanda Rybin Koob: I was also fascinated by Warshall’s description of Rachel Carson’s discipline: that though they won major literary awards at the same time, she and Marianne Moore never spoke outside of that event because that relationship wouldn’t have served the agenda of Carson’s work. He compares Carson to Emily Dickinson, who similarly curated a specific life and specific relationships all to suit her work first. She didn’t “disperse herself.” A couple of figures who, perhaps, rejected the dystopian aspects of community in order to create their visions, their better worlds.

(Of course this also reminds me of an inscription to a donated copy of Howl held at Naropa’s Allen Ginsberg Library, where Ginsberg writes: “Absolutely No Discipline! It’s a CIA plot!”)

Photo by Amanda Rybin Koob.

Groetsema: Warshall critiques the many environmental memoirs he receives in the mail to review by saying they all are predicated on a separation between humankind and nature, a method that reinforces the abstraction and objectification of nature as something outside of lived experience, or in this case, something outside of our shared community. The perspective of this writing, he says, is always from the first person and always starts the same way: “Here I am out in the woods.” Warshall’s critique suggests that the “I” is an impossibility; it is incoherent when there is “We.” How do we look at community from an ecological point of view? Is writing a kind of biome?

I think about the handouts that writer Rowland Saifi showed me from the Environmental Studies: Survival Skills course that had been taught by Richard Dart at Naropa for many years. I was struck by the opportunity to see them and read through Dart’s notes, illustrations, and stories, particularly the exercise titled, “25 Steps to Improved Nature Observation and Preparedness” — I read Step 5 aloud: “Imagine that you are a part of everything” and I do.

Rybin Koob: I love the frame of “imagine that you are a part of everything” as a survival skill.

Groetsema: Warshall’s own literary practice starts with taking “field notes” and similarly to Ed Sanders’s view, is a practice of obsession. Eventually, the notes become a curated work. Warshall urges that writing should not be “data, but agenda” — that which is produced by intention and obsession. Writing that is timely, that speaks to a current moment from all times and places, that which approaches sublimity.

Does our understanding that our individual existence is both present and not present; in relationship to things and not, allow us to be free thinkers and free writers? Does the understanding that the possibilities of life are infinite and dualistic, change the way we construct and imbue?

Community presence

The discussions of what could constitute community have been a part of a long tradition during SWP at Naropa.

Photo by Jaime Groetsema. Courtesy of Naropa University Archives.

When I first saw the cover of this student newsletter from 1980, I appreciated the line drawing but felt the drawing did not really match the title “Community at Naropa,” as the empty chairs and empty, linear space, seemed to convey a lack of “community” which also seemed out of place on the cover of a student newsletter (i.e. community publication). I realized then that what I originally saw as a lack of community, was instead pointing to the productivity of the community — that the people I assumed should be filling the space were actually out doing things in their, and with their, many communities.

Rybin Koob: I also imagine Naropa’s version of Marcella Durand’s “Rob” or similar figure grumbling while he stacks the chairs and cleans up after the people who’ve left the scene. I wonder if others in the community were out and about because, as Robin Blaser says in this panel, “seeking out the best minds is all we can do” (he repeats it in a deliberately loud and crabby voice, with humor).

Bits and pieces

Groetsema: And there is a dialogue about dreams in Steps to an Ecology of Mind[2] (first printed in “Approaches to Animal Communication” in 1969) between anthropologist Gregory Bateson and his daughter Mary Catherine Bateson:

[M]: But if a person is afraid of something which he knows will happen tomorrow, he might dream about it tonight?

[G]: Certainly. Or about something in his past. Or about both past and present. But the dream contains no label to tell him what it is 'about' in this sense. It just is.

[M]: Do you mean it’s as if the dream had no title page?

[G]: Yes. It’s like an old manuscript or a letter that has lost its beginning and end, and the historian has to guess what it’s all about and who wrote it and when — from what’s inside it.

And here a clipping noting a lecture given by Gregory Bateson at Naropa during SWP in the Naropa Student Newsletter #22 from the 1970s:

Photo by Jaime Groetsema. Courtesy of Naropa University Archives.

Rybin Koob: I was disappointed that the descriptive information about the 2003 recording we listened to for this post mentioned a question posed by Bobbie Louise Hawkins that ended the panel. Yet the recording itself cuts off Robin Blaser’s presentation at the end, and there are no questions recorded. When was this recording erroneously cropped? What was Hawkins’s question, and what were the answers? I guess we’ll have to keep guessing based on what else is inside, what remains.

Groetsema: Today, I received a link to a zoom recording of Marcella Durand’s writing workshop during this year’s 2021 Summer Writing Program. I downloaded the files, created a folder for them, naming them, saving them, starting the process of preservation, and then hoping, too, that they last for at least forty years.

1. G. Thomas Tanselle, “The World as Archive,” Common Knowledge 8, no. 2 (2002) 402–06.

2. Gregory Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000).

Community Praxis in Naropa Audio Archives