'Here I am out in the woods …'

Alternative communities and writing, part 1

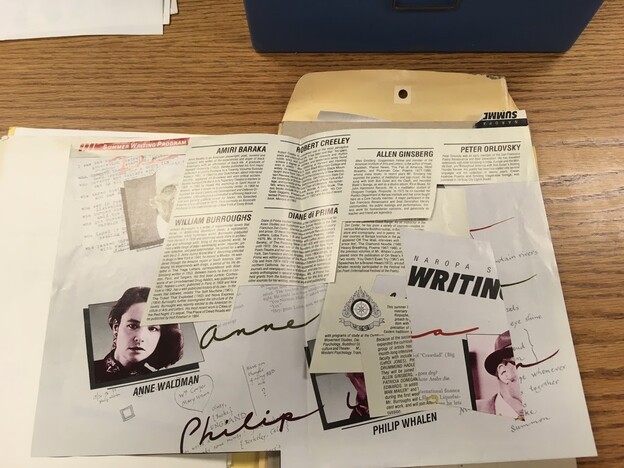

Naropa Archive Recording Title: Alternative Communities and Writing Date of Recording: June 9, 2003 Panelists: Anne Waldman (Chair); Eleni Sikelianos; Peter Warshall; Ed Sanders; Marcella Durand; Robin Blaser.

Jaime Groetsema: The Summer Writing Program came out of the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics (JKS) at Naropa University. JKS was officially established in 1974 along with what has been called the Visiting Poetic Academy, the Summer Institute, amongst other conventions, and now the Summer Writing Program (SWP). SWP is a writing intensive that brings together an annual collective of visiting faculty of poets, writers, musicians, visual artists, performing artists, dancers, and so on, to discuss writing, community, and collaboration. This summer writing intensive just celebrated its forty-seventh year.

Yet we know that the movement of ideas that came together to create this program were sparked much earlier when, as I’ve heard the story shared many times, Allen Ginsberg and Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche were first introduced to each other during a shared cab ride:

|

Ginsberg asked Rinpoche to teach him about Buddhism |

: |

Rinpoche asked Ginsberg to teach him about Poetry |

And so a lineage involving the dialectical practice of writing, influenced by the spiritual practice of Tibetan Buddhism, was born. Ginsberg was asked to create a school of writing, and he brought Anne Waldman and others into the fold.

Much like other experimental communities-schools, like Black Mountain or the Highlander School, or even the Bauhaus, JKS and SWP remain, while the other schools do not.

JKS and SWP act as a lens refracting the past into the present, and are a testament to a potentiality of the relationship of theory and practice (praxis). The school today in 2021 of course looks much different than it did in 1974. Yet to say that the many durations of time have caused changes is not important here, but rather this continual potentiality; its viable and unique forty-seven-year (and ongoing) pursuit of what the practice of writing, community, and collaboration can mean.

So when I listen to the “Alternative Communities and Writing” SWP panel from 2003, I think about a definition of community that can be new every year and at least forty-seven years old; that can regenerate and connect with writing at each instance, and how these various ways of thinking about what shapes community work by way of both intention and chance.

Amanda Rybin Koob: This also makes me think about the various traditions or aesthetics that poets and artist have brought to Naropa (such as “Beat,” New York School, the broad and vague “experimental,” or Anne Waldman’s Outrider poetics) and how those pass through the walls and minds of participants during the brief three to four weeks folks are on campus for the SWP intensives, and how that differs from other kinds of collectives. The JKS SWP is both short and long, in Boulder and apart. It seems to me a beautiful manifestation of multiplicity and affinity without cohesion.

I also remember Ed Sanders’s description of the Beats as a “deliberate creation of a mega community” in the panel we discuss here.

Groetsema:

My Notes on a Potential Definition of Community

Community is everything that is here now, that was before, and that will be after.

The possibilities of community are the possibilities of how things relate; that things can relate and that the ways in which they relate are multiple, mutable, inconsistent, with tension, and cannot be fully described, depicted, or understood.

What are your communities?

That things relate in a variety of ways is a consequence of being. Yet, can one shape being? Can one choose what to make, write, and say in the particular contexts of one’s being?

How do you relate to them?

During the 2003 SWP panel, Marcella Durand says that the poet is a kind of writer, the writer is a kind of artist, the artist is inherently creative, and that this community of creative people is what stands against commercial pursuits. That creative work cannot, by necessity, be beholden to commercial interests: Yet, I wonder, how does one survive?

Does one need to sell creative work to justify making it?

Poet << >> Writer << >> Artist << >> Creative Community

Rybin Koob: This multidirectional visualization of community and individual also reminds me of how Peter Warshall describes writing itself, from field notes to craft/intention, to agenda, to political timing, to community (and back again).

Groetsema: By way of a randomized set of constraints, I flip to writing exercise #166: Parents As Two Continents in Brian Kiteley’s The 4 A.M. Breakthrough and read the first line aloud: “Write about your own parents in essay format.” As I think of what to write, I notice that the previous page of Kiteley’s book says: “Our family and our closest friends form a community unlike any other we belong to.” [1] Here, parents and family and friends can be anyone, depending on how one defines those terms and how one thinks about lineage.

In the “Alternative Communities and Writing” panel, Eleni Sikelianos speaks about “series of communities”: geographical, temporal, personal. The personal is her family; her relationships with her family are a community. She notes the complexity of such personal relationships — with her father and with her grandmother — and I hear references to Sikelianos’s hybrid memoirs The Book of Jon [2] and You Animal Machine [3] before they were published.

I double-checked the publication dates of the books to be sure I can write what I just wrote and came across an essay by Sikelianos about her genealogical connections to Anne Waldman and poetry. Sikelianos writes: “What we hadn’t known when Anne held me in her arms, or what we hadn’t yet formulated, is that there was a strange configuration already underway, about to arise and inscribe itself further.”[4] A configuration made by a variation of pasts in the presence of forms of convergence.

Sikelianos reads from Marguerite Young’s 1945 study of two experimental communities, titled Angel in the Forest: A Fairy Tale of Two Utopias: “Marguerite Young asks, ‘How to erect, even in heaven, to say nothing of earth, community without impedimenta, ties, relationships?’ An undertaker answers her, ‘Nobody could remove the flaws from the universe without destroying the universe.’”[5] If the flaws must always be present, then there is no perfect space of existence. And here, too, all things exist in relationship to each other.

Rybin Koob: Thinking about there being no perfect space of existence, no perfect community, and also Sikelianos’s later mention of mutual aid, reminds me of a talk that Dean Spade and Mariame Kaba recently gave at the American Library Association 2021 virtual conference. In response to the question “How do we keep going?” (offering care to our communities through crisis) Spade said: “Feelings of burnout or overwhelm, sometimes they’re related to … a cultural norm around avoidance.” And then: “To me, the antidote to that avoidant feeling is a feeling of being on purpose. Feeling deeply like I know why I’m here … and I want to build my muscle for liking people I’m working with even when they’re annoying … because it’s a long haul, and I plan to just fight until I die.” This is one of the best pep talks on imperfection in community that I’ve ever heard, and I certainly saw the ideals at work in Naropa’s communities.

This is also echoed in Marcella Durand’s brief talk on the panel recording about “Rob” (not his real name), an active participant in the New York poetry scene, the guy who sweeps the floors, stacks chairs, and picks up trash while also yelling at you for not attending enough readings and not supporting the community enough. She says that an “elasticity of acceptance” must accommodate even the most annoying and difficult people in our communities, because we are all essential in creating a space that can push against other forces of oppression in American culture.

Groetsema: I wanted to learn more about Marguerite Young. I perused an online resource and found an anecdote that Young’s grandmother thought Marguerite was the reincarnation of her grandson Harry. I read the interview from where this story and citation comes: “When I was three my parents went their separate ways. I have no memory of parental relationships at all. I lived with a grandmother who idealized me and projected upon me all her own dreams of artistry and poetry. … One reason that she was so drawn to me was that two weeks before I was born her little grandson Harry died suddenly of diphtheria. … She believed that I was God’s gift to her, that little Harry had been born again in me.” [6] The writer both Marguerite and Harry at the same time.

Sikelianos also discusses the complexity of communities as a dualistic “dystopian-in-utopian” experience and counters this notion with the pursuit of idealized communities and its impact on culture, alongside the production of literature, where imagined communities can be of “any form we make.” The suggestion then, it seems, is to concede the messy, complex, multivalent material of life. The worlds depicted in writing are similar, yet expand lived experience by helping us to resolve the dualistic, or dialectical, tension of dystopia-in-utopia.

Someone gave me a copy of Natalie Goldberg’s Writing Down the Bones from 1986. I flip to where a bookmark was placed and read aloud: “We talked about our voices as writers — how they are strong and brave but how as people we are wimps. This is what creates our craziness. The chasm between the great love we feel for the world when we sit and write about it and the disregard we give it in our own human lives.” [7] Goldberg resolves the dualism by saying we must “carry the poem out” into the world and enact the poem there.

Rybin Koob: I think I’ve heard this notion before, but have never known how to do it. Maybe the obvious answer is activism? It recalls Warshall’s ideas of writing, agenda, political timing, and community, where a writing community must necessarily be engaged politically.

Groetsema: The discussion of human life and relationships is, of course, only one piece of community. Another notion that Sikelianos points to is the relationship of material and material culture to community. She seems to ask: If everything is connected, and humans form a global community with all things, how do we account for what might seem to an individual consumer of cellphones, an object in total, but an object that in actuality relies on the continual consumption of nonrenewable resources from conflict areas in the Democratic Republic of the Congo? Despite our understanding that materials are nonrenewable, that they perpetuate conflict and exploitation, that the object itself sends microwaves through our body and hands and brains, we find them a necessity for our most basic, most important, most essential day-to-day activities, which in turn make up our community, i.e. our social life, our working life, our personal life, our health, our errands, our connections, and so on. If literature helps us to examine and try to resolve in some manner this dualistic quality of being, as Sikelianos points out, what do we begin to imagine instead?

Rybin Koob: I loved Sikelianos’s idea here that communities are permeable (in both negative and positive ways) — this brings me back to Goldberg’s resolve and helps answer my question about what it means to bring the poem, or the bravery of poetic voice, into the world: permeability of borders.

1. Brian Kiteley, The 4 A.M. Breakthrough (Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2008), 216–217.

2. Eleni Sikelianos, The Book of Jon (San Francisco: City Lights Publishers, 2004).

3. Eleni Sikelianos, You Animal Machine (The Golden Greek) (Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 2014).

4. Eleni Sikelianos, “The Lefevre-Sikelianos-Waldman Tree and the Imaginative Utopian Attempt,” Jacket Magazine 27 (April 2005).

5. Marguerite Young, Angel in the Forest: A Fairy Tale of Two Utopias (Normal, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 1994).

6. Charles Ruas, Conversations with American Writers (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1985), 94–95.

7. Natalie Goldberg, Writing Down the Bones (Boulder: Shambhala Publications, Inc., 1986), 128.

Community Praxis in Naropa Audio Archives