Archival poetics pt. 3

Building an archive with Eleni Sikelianos: memory, vision, body

Rybin Koob: Eleni Sikelianos, poet and teacher, follows Steve Dickison’s reflection on archives and naming during the 2012 Naropa Summer Writing Program panel Archival Poetics and the War on Memory:

01:03:02: I want to underline Anne’s call here, to go and listen to the archives here. Amazing, amazing things, available just a few feet away.

01:03:18: The question is: how to interrogate the remains? What are the remains, and what are the archives that record them?

01:04:48: Derrida in Archive Fever states: “archive takes place at the structural breakdown of memory. Archive itself invites forgetfulness and thus always works against its own aim, erasing memory as it creates it.”

Memory for forgetfulness (Mahmoud Darwish, cited by Steve Dickison). Archive invites forgetfulness (Derrida). The relationship between memory, archive, and the body is articulated next as Sikelianos discusses the micro (individual body as document, family history as archive) versus macro (biological diversity, war, mass migrations …) and the necessary context of specific political regimes and their impact on lived experience (e.g., the archive of Pol Pot’s genocide in Cambodia).

Groetsema: I think immediately of Sikelianos’s own work, which synthesizes those relationships between memory, archive, and body into books that push back and forth, interweave the micro and macro. Make Yourself Happy, You Animal Machine, and The Book of Jon all bring together personal histories around larger concepts, rather: the impacts of extinction, immigration, and the visionary within capitalist social structures.

In Make Yourself Happy, the archive begins on the dedication page: “for us: our past, present, and future,” and I am struck by such a concise description of what an archive is and does, what an archive takes as purpose.[1] In the first pages of the book, we read meditations on what happiness is or could be. We’re thrown into a Likert Scale Test and forced to come out of it having learned something. Then, we contemplate the happiness of a Bird, Civilization, a dream, amongst others — all interconnected. And finally, after we follow through memory, archive, body, we find another simple resolution: “You are the beast / be Happy.”[2] And my thought now about this section of the book is that it functions like a dialog; we’re meant to start and end with archive.

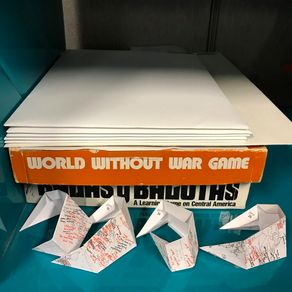

The second part of the book deals directly with extinction as a macro lens. We read through many pages of extinct species around the world: about Gerygone insularis, we read “no records of the species since 1928, when it was heard, not seen; none seen or heard since.”[3] At the end of this section, we are asked to cut out, fold, and adhere “the animal globe,” a small 3-D globe of the world with Sikelianos’s hand charting the extinctions. This is beyond an exercise of thoughtful making but very literally the act of making a world of extinctions and acknowledging that history and responsibility. No doubt, even more extinctions could be added to this world in the six years since it was published.

I made the world of extinctions. But I couldn’t put it together.

And left the world as small crab-shaped pieces near two board games I have yet to catalog: World Without War Game and Balas y Balotas.

And perhaps it was because I couldn’t face the true impact of so many extinctions that I became transfixed instead by the outline of the pieces of that world that remained and by the black borders surrounding the pages of the book — this melange functioning like early images of the world, succinct with firmament, meanings outside of the orbis.

Still, reminds me of fol.1r from LJS 196, currently held at University of Pennsylvania Libraries:

A supposed nineteenth-or-twentieth-century painting, the cataloger of this manuscript writes: “On the Persian leaf, the miniature of a scene of a man kneeling at the mouth of a cave with another man kneeling before him enclosed in a rondel is painted over the text on the page.” Here a painted world circled by a circular disc (roundel), a frame of steel (rondel), or poem (rondel). An additional way of thinking about how material and meaning change over time and ways to ask where and how memory, vision, and body overlap with “for us: past, present, future.”

An answer, perhaps, is in What I Knew, where readers follow Sikelianos across the globe and back home by way of an exegesis of personal experience and through a changing global landscape of place. And still, while we read of these lives, there are pieces of extra-present, unveiled, specific, moments of living:

So sun befall me Baltimore

Rainbow sleaze Guantanamo

Radiant thaw in Chicago

Unsaying

If god is a mood

Or god is

In this house

“I’m gonna step on bacon.”

–Eva, age 7, 12:46pm, Thursday, March 28, 2013, standing on the counter

“Seriously!” she says when I say I’m writing this down.[4]

Shall we all step on the bacon?

Rybin Koob: Sikelianos is the first on this panel to explicitly name documentary poetics, including Charles Reznikoff who said:

01:08:50: “I didn’t invent the world, but I felt it.”

Reznikoff, for example, tracked legal documents from 1885–1915 relating to the transformation of the national consciousness during the shift from agrarian society to industrialization. He also worked with the Nuremberg Trial documents to create his series of poems called Holocaust.

01:09:35: He is particularly instructive to see how focusing on the micro makes the macro more real.

Sikelianos poses questions and creates a constellation of thinkers and poets who have meaningfully engaged such questions. These thinkers inform her archival poetics:

01:09:44: And just a quote from the French philosopher, Paul Ricoer: “The most valuable traces are those that are not intended for our information.”

Groetsema: Yet we make information out of them.

Rybin Koob: Then, she asks:

01:09:57: What is the relationship between archive and vision? In Reznikoff, the line breaks carry the brunt of the emotional work. For me, in family histories or elsewhere, the imagination organizes the evidence in various ways, putting material against material, form against form, creating texture and palpability. Imagination inserts itself and expands the real.

Sikelianos invokes visual artist Renée Green and poet Lorine Niedecker, discussing the glut and surplus of archive, and what Sikelianos calls the geological archive in Niedecker’s work, “the natural sedimentation.” She invokes the Russian artist Ilya Kabakov, who works with the archives of trash, and weaves her own lyric imagination with his words, continuing this poem-talk. Below are our attempts at isolating the threads:

Sikelianos, quoting Kabakov:

01:12:06: Should everything without exception before his eyes in the form of an enormous paper sea be considered to be valuable or to be garbage? And then, should it all be saved, or thrown away?

We’re reminded of Kurt Schwitters’s Merz, assemblages and collages created from the breakdown of the known and familiar world during and after World War I: “One can even shout with refuse, and this is what I did, nailing and gluing it together.” And at the same time: “Merz means to create connections, preferably between everything in this world.”[5] Connection through breakdown, against or within forgetfulness.

Sikelianos:

01:12:26: It isn’t just a receptacle for the dead or forgotten, not a trash heap, but a living network of fact — and fact both in decay and fact in rehabilitation — that feeds us.

Sikelianos, quoting Kabakov:

01:12:39: “To deprive ourselves of these paper symbols and testimonies is to deprive ourselves of our memories. All points of our recollections are tied to one another. They form chains and connections in our memory, which ultimately comprise the story of our lives.”

Sikelianos:

01:13:00: The poet sticks her fingers into the holes, to find not what is reported, but what is felt there … she reinterprets event, giving it music and heft. She reconfigures and confounds organizing systems to achieve a new method of understanding, so the forms of history are not dominated by one way of apprehending.

Here the poet is in service to the archive and to history, to complicate institutional ways of organizing and understanding, creating something human and lyric, though no less real.

1. Eleni Sikelianos, Make Yourself Happy (Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 2017).

2. Sikelianos, Make Yourself Happy, 54.

3. Sikelianos, Make Yourself Happy.

4. Eleni Sikelianos, What I Knew (New York: Nightboat Books, 2019), 45.

5. Kurt Schwitters, “Merz” (1924), in Das literarische Werk (Köln, Germany: DuMont, 1981), 5: 187.

Community Praxis in Naropa Audio Archives