Interlude: Rereading the beginning

Featuring Anne Waldman

Jaime Groetsema: Whenever I think about archives or the material culture that could possibly constitute them, I try to define what an archive is.

Are archives necessarily institutional? Is an archive simply a collection of things representing something? Does it matter if the collection of things is metaphorical, commercial, or virtual? Must the materials of the archive represent an event and must they include a nod to the longevity of narrative and the pursuit of preservation? Is an archive still an archive if it is inaccessible? (I’ve written more specifically about archives and language over at Reconfigurations.)

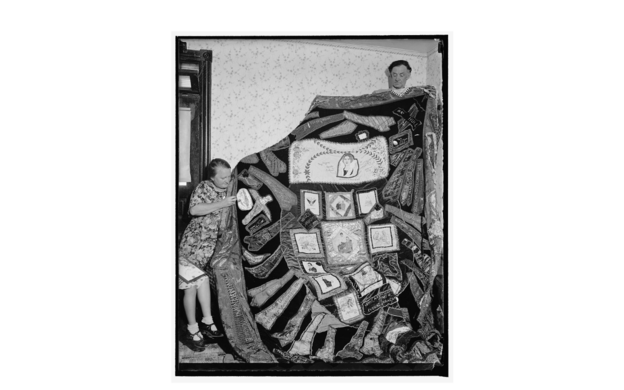

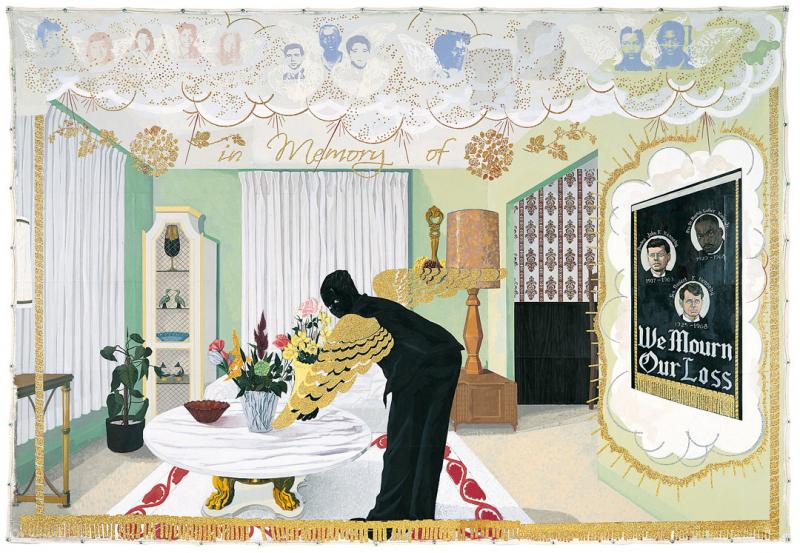

And often when I try to answer these questions, I have no answers. I read books, articles and essays, look at artifacts and objects and art. The things I look at always change. Today, I am thinking about John Ridener’s book From Polders to Postmodernism: a Concise History of Archival Theory,[1] a postcard Sol sent me of a Carbro print of Frida Kahlo by Nickolas Muray (Frida Kahlo on a Bench #5), the historical quilt (image above)[2] made by Ethel Sampson in 1937, and the “Souvenir” series of paintings made by Kerry James Marshall in 1997 and 1998 (image below).[3] (Kerry James Marshall’s work, including the piece Souvenir I is currently on display at the Seattle Art Museum as a part of their “Figuring History” exhibition).

Can a historical painting or a historical quilt function as an archive? Do the combined references of each object, when read together in a frame, constitute a collection that represents an event? Moreover, each object instigates thoughts about preservation in a dualistic way — on the one hand through the recollection and memorialization of significant figures represented by their painted images or pieces of clothing. On the other hand, each is a cultural artifact that requires care to ensure the objects’ longevity.

From the archivist’s perspective, Ridener elucidates that, “The current [archival] paradigm is the result of a group of archivists and theorists who write from varied perspectives but who share a range of philosophical and critical values that stress context, interpretation, and critical reading as a framework to create archival theory.”[4] Ridener is contrasting this current mode of archival practice and theory with a past mode that largely relied on a few, well-known individual archivists to pass on methods of practice. As I read the book Staging the Archive, Ernst Van Alphen seems to respond by asking, “But what exactly does it mean that archives are no longer considered to be passive guardians of an inherited legacy but instead active agents that shape personal identity and social and cultural memory?”[5]

Does it matter that, as Arlette Farge writes in The Allure of the Archives, “The archives are not a stockpile that can be drawn from at one’s convenience. They are forever incomplete, akin to what Michel de Certau’s definition of knowledge as ‘that which endlessly modifies itself by its unforgettable incompleteness’”?[6] I keep reading the quote and see: by its unforgivable incompleteness.

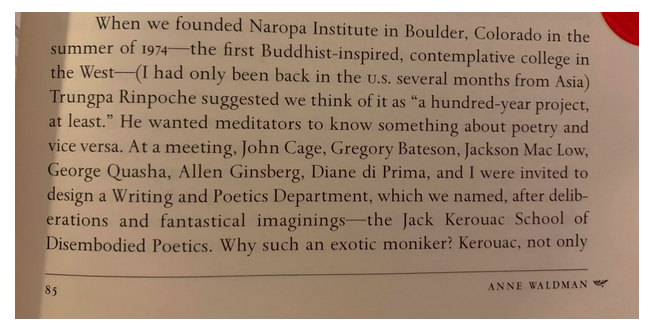

When we shared our first Commentary post, “Here I am out in the woods,” with Anne Waldman, she noted that she wasn’t invited by Allen Ginsberg to create the writing program at Naropa, but that she was invited by Trungpa and some of his key students at the same time Ginsberg and Diane di Prima were also invited to read their poetry and teach workshops in 1974 in Boulder, Colorado. Towards the end of the summer — at a famous meeting that included Trungpa and Ginsberg, di Prima, John Cage, and others — the invitation came to create a poetics program. Naropa had not been founded. This distinction is important because it situates Anne as a poet, curator, and editor, and as someone who was already working with and for poetry for a number of years at The Poetry Project (which she had helped found in 1966), traveling to give workshops and readings and the like. She had already published with Corinth Books and Kulchur and Bobbs-Merrill, and was well-known for her readings. She had contextualized her particular path with poetry as coming to the fore in 1965 when taking her “Vow to Poetry” at the Berkeley Poetry Conference.

Anne sent additional notes and references which she has kindly allowed us to share here. And what is striking is that her role in the creation of the writing program at Naropa, as stated above, has been shared in print many times. We added the text captures below to directly point to her references where she explicitly states this culmination of events.

Anne Waldman: So yes include my response … and maybe a bit more to add … I think there’s a piece called “Take Me to Your Poets” in my book Vow to Poetry.[7] Might be helpful.

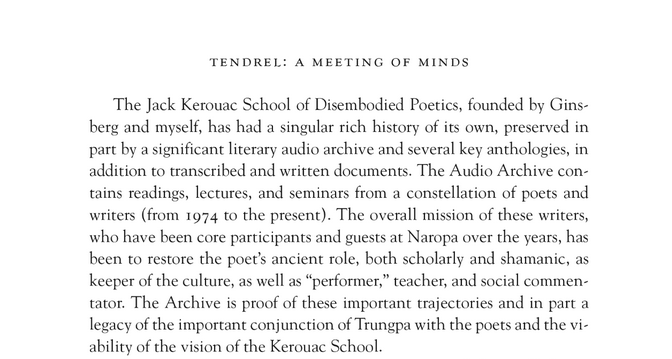

Also a piece entitled “Tendrel: A Meeting of Minds”[8] that appeared in a Book from France about CTR. I also have a copy somewhere —

I was living in Cherry Valley at Allen’s farm that summer — and my recollection is that Allen and I traveled together to Boulder. We had met briefly at Berkeley Poetry Conference in 1965 and had gotten closer in NYC. We crossed paths in London, read with Burroughs in Canada, etc. We had an encouraging phone call when I was in college in VT. I was already interested in the New American Poetry, and more radical practices than more formal left-hand margin prosody. Bennington had an impressive range, however, of active writers: Howard Nemerov, Bernard Malamud, Georges Guy, Barbara Hernstein Smith, Stanley Edgar Hyman. There was an interesting poets visiting series. I enjoyed meeting May Swensen, John Berryman, and got to know Claude Fredericks who was a real treasure, an excellent printer. He gave advice on Angel Hair. I also studied with Georges Guy, French poet, who had translated Kenneth Koch. I was editor of the magazine SILO, and wanted to see if Allen would visit Bennington. I think he was off to India at that point.[9]

I had also met the great Mongolian Lama Geshe Wangyal (I speak about him in a recent interview from Boog Press[10] that did an AW tribute in 2020[11]), in the early Sixties.

The link to the Poetry Project is important for me … I had already been involved with the pre-Arts Projects at St. Mark’s before 1966 — specifically Theatre Genesis and open readings at the Church — (I was in a play at Genesis while still in school) and wanted to bring some of that Founding energy and experience along from there to this new exciting developing possibility in the negative ions of Boulder. Infrastructure Poetics.[12] Applied Poetics.

And there was such a focus on the readings, the events, the politics, the workshops and small press publishing — we were part of the Mimeo Revolution. (See the books: All Poets Welcome: The Lower East Side Poetry Scene in the 1960s by Daniel Kane and A Secret Location on the Lower East Side by Steve Clay and Rodney Phillips[13]). Lewis Warsh and I had already founded Angel Hair in 1965 having met in Berkeley. I was living on St. Mark’s Place, after having grown up on Macdougal Street. There had been some years of community work on the Lower East Side through The Project years. It was harder, I would say, to be a woman during these early years, sometimes not getting credit for all the work behind the scenes, or consideration of myself as a committed poet.

Daniel Kane, who wrote the book All Poets Welcome, originally had no idea about where I had come from — artistic bohemian parents, mother living in Greece ten years, father who had spent time in Provincetown, started as drop out swing piano player. So, and so on … he had been interviewing the “guys” about me. Infuriating. I also made sure we were taping and archiving the readings. A practice I observed from Paul Blackburn at the open readings at St. Mark’s before the Project even started. That continued at Naropa. Not with the best technology or equipment but there’s a record. And I had instigated that.

Groetsema: Additionally, from an interview in the Journal of Beat Studies between Anne Waldman and John Whalen-Bridge:[14]

Waldman: I was already on a path from an early age. I talk about taking a “vow” at the Berkeley Poetry Conference [15] in one of The World anthologies.[16] Also the Beats At Naropa anthology might be useful.[17]

Think my profile on Wikipedia needs inspired critical attention. So limited with all this important stuff. I need a serious scholar to get it all right and be inclusive of these strands and early dimensions …

Groetsema: A few days later, Anne reads part of the introduction of the New Weathers anthology to me over the phone, a book based on lectures at the Jack Kerouac School at Naropa (coedited with Emma Gomis, and to be published by Nightboat in 2022). And there is so much that is so important but what sticks with me is the phrase: “the practice of rereading.”[18]

1. John Ridener, From Polders to Postmodernism: A Concise History of Archival Theory (Duluth, MN: Litwin Books, 2008).

2. “Famous historical quilt. Washington, D.C., Aug. 17. Joseph's coat of many colors had nothing on this unique quilt which is now being completed by Mrs. Ethel Sampson of Evanston, Ill., after six years of collecting. Parts of wearing apparel from President Roosevelt, Mrs. Roosevelt, members of the Cabinet, diplomats and notables from all over. From Hollywood Bing Crosby sent a tie while Mae West and Shirley Temple contributed parts of dresses. Former Emperor Haile Selassie's neckties and a linen of Winsor, are also included on the quilt. Diapers from the Dionne Quintuplets are also prominently displayed, 8/17/37.” Harris and Ewing, August 17, 1937, photograph, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

3. Kerry James Marshall, Souvenir I, 1997, acrylic, collage, and glitter on unstretched canvas, 108 x 157", Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, © MCA Chicago. Photo: Joe Ziolkowski.

4. John Ridener, From Polders to Postmodernism: A Concise History of Archival Theory (Duluth, MN: Litwin Books, 2008), 101.

5. Ernst Van Alphen, Staging the Archive: Art and Photography in the Age of New Media (London: Reaktion Books, 2015), 14.

6. Arlette Farge, The Allure of the Archives (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013), 54.

7. Anne Waldman, Vow to Poetry: Essays, Interviews, Manifestos (Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 2001), 85.

8. Anne Waldman, “Tendrel: A meeting of minds,” in Recalling Chögyam Trungpa, ed. Fabrice Midal (Boston: Shambhala, 2005), 419–38.

9. For more information see: Anne Waldman, “Anne Waldman: 1945–” in Contemporary Authors Autobiography Series, Gale Research Series 17, (1993): 275–76. Excerpt published on Poetspath.com.

10. Boog City, “Anne Waldman at 75,” Boog City: A community newspaper from an extended community 136 (2020).

11. Nathaniel Siegel, “Nathaniel Siegel’s interview with Anne Waldman,” Boog City: A community newspaper from an extended community 136 (2020).

12. Anne Waldman, “Personal Statement on Infrastructure Poetics,” Forum for world literature studies 1, no. 1 (2009).

13. Daniel Kane, All Poets Welcome: The Lower East Side Poetry Scene in the 1960s (Oakland: University of California Press, 2003), and Steve Clay and Rodney Phillips, A Secret Location on the Lower East Side (New York: Granary Books and the New York Public Library, 1998).

14. John Whalen-Bridge, “Trungpa, Naropa, and the outrider road: an interview with Anne Waldman,” Journal of Beat Studies 2, (2013): 31–50.

15. Berkeley Poetry Conference 2015 Committee, “Looking backward to the BPC 1965,” 2015.

16. Anne Waldman, “Running off The World,” From A Secret Location, ed. Steve Clay.

17. Anne Waldman and Laura Wright, eds., Beats at Naropa: An anthology (Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 2009).

18. Anne Waldman, phone conversation with author, August 11, 2021.

Community Praxis in Naropa Audio Archives