Metaphor and social media in the 2020 election

by James Sherry

Personal, political, and climate conditions change continuously, as does poetry, its syntaxes, and uses of metaphor. Within certain ranges, readers simply accommodate change.

The appearance of Beat Poetry at the Six Gallery in San Francisco and the ensuing obscenity trial quickly changed reader expectations. Language writing and its political techniques changed the poetry world over a generation. The Black Arts Movement sought political change through poetry, as in Amiri Baraka’s

Poems are bullshit unless they are

Teeth or trees or lemons piled

On a step.[1]

Change outside expected ranges such as rapid increases in global temperatures, the sudden effects of introducing digital technology into poetry, and heightened increase in income inequality challenge the ability of poets (and other citizens) to adapt. Some poets disregard changes around them; some poets engage; some poets are repressed by them. But change at certain speeds is difficult to ignore, to accommodate, and to write with.

To make people more receptive to change, metaphor unifies experience and thought processes at different scales. Metaphors can make absurd connections in surrealism, link political techniques of Language writing to election choices, and link language to material in the Black Arts Movement.

In their talk at Black Hat, “Hacking Ten Million Useful Idiots: Online Propaganda as a Socio-Technical Security Project,” Pablo Breuer and David Perlman examine how rapid change from norms can be achieved with social media:

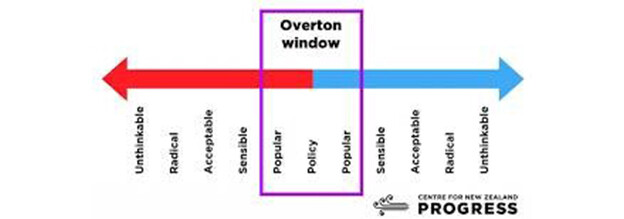

Think about what happens when Trump proposes a policy on the far right? Given a range of acceptable discourse known as the Overton Window, it would take a lot of work and a long time using traditional public relations strategies to make his fairly radical notion acceptable. Instead of the slow method, start with a “really crazy pitch” and rally a small, vocal fringe to the outlandish notion. Trump suggested, for example, that climate change is a fiction invented by the Chinese Communist Party to destroy Capitalism.

If Trump can get enough people talking about it, the Overton window stretches to include both the wacko hypothesis and a fairly radical target policy, like reducing funding for clean air and water. The target policy suddenly seems reasonable compared with the wacko opinion and many Trumpists accept it. Bots continually rephrase the crazy proposition, keeping it visible to larger populations and diffusing opposition: truth is accepted, included, and forgotten, while monstrous lies are constantly reiterated.

In the scale-free networks of climate systems, people “form network links at a much faster rate than you lose links.” The governing principle is not creating the link to the wacko opinion; you can see how easy that is. The problem is losing the link, untying specious attachments, and becoming convinced that what you heard and considered is not true.

The ethical question is whether to use such tools to win elections, promote environmental targets, or introduce readers to new poetry. How much exaggeration makes sense in promoting the goal of truer relations to our surroundings? Some people therefore stick to the facts. Some people think that they need to imitate outlandish libertarian behavior. Some use tools that connect, disconnect, and reconnect, such as metaphor, adding “I am an ecosystem” to the metaphor “I am an individual.”

Scaling up: alleviating poverty through green jobs connects social benefits with labor so workers in both government and construction learn to operate together on unfamiliar terrain. The benefits of creating those difficult linkages might be enormous. “Fortunately, the same climate-change measures that generate higher energy-related costs can also generate substantial resources to cover those costs.”[2]

How we speak about those practices also needs to change. Facts frequently fall flat. Mentioning additional costs and efforts drives corporate leaders and developers into a frenzy of denial. Many posture that they require complete, effortless transition to sustainability to be performed for them but won’t accept government regulation as a method to achieve it. So many rejections.

Poetry builds coherent personal, political, and environmental points of view through the channels of metaphor and changes in standards of syntax. Using these and other techniques establishes new connections across modes of thought. These methods can substitute for facts when facts fail. They convince because they show that our selves are similar to our surroundings; not identical but comparable.

Metaphors develop relationships across extraordinary distances and scales. Metaphor convinces more readily than facts, working as it does directly through the biological syntax of channels in the brain. This interaction both between and within entities confirms our species’s desire for connections between human and other components of the biosphere in poets like Rae Armantrout:

The child wants his mother

to put her head

where his is, see

what he sees.[3]

But if poets write directly to influence politics, do they lose their connections to themselves? Anxiety threatens in the social-media age if we lose contact for even a minute.

Poets who address the public sphere directly quickly change the terms of public engagement to improve conditions for individuals oppressed by political systems. From Catullus’s attacks on the behavior of Roman political figures to Shakespeare’s cheerleading for the monarchy to Baraka’s critiques of US military expansion, poetry engages multiple ways of ordering words and leaps of metaphor. Group (political and environmental) syntax evolves through poetry and if not in verse then using poetic technique.

Seen from a distance, poetry addresses politics and selves through ecological linkages that change people’s minds. Although there’s an inherent ethics in preserving human-friendly ecosystems, morality and habit will tend to vary in different societies, habitats, and conditions. There is no correct syntax and no correct politics. Syntax and politics are both dependent on situation, and that’s how we defeat Trump. Revising syntax and metaphor establishes new composite entities — a social evolution, mother and child, president pleading for voters to see it his way.

1. Amiri Baraka, Liberator (January, 1966).

2. Chad Stone and Matt Fiedler, “The Effects of Climate-Change Policies on the Federal Budget and the Budgets of Low-Income Households: An Economic Analysis,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 9, 2008.

3. Rae Armantrout, “Bubble Wrap,” in Money Shot (Middleton, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2012), 23.

James Sherry is the author of thirteen books of poetry and prose, most recently The Oligarch: Rewriting Machiavelli’s The Prince for Our Time (Palgrave, 2018) and Entangled Bank (poetry, Chax Press, 2017). His fourth book on environmentalism, Selfie: Poetry & Ecology, will be published in 2021. He is the editor of Roof Books and started the Segue Foundation, an international arts organization, in 1977. He lives in NYC and the Hudson Valley.

Poetry and the 2020 election