On Frank O'Hara’s Lunch Poems / queer / attention

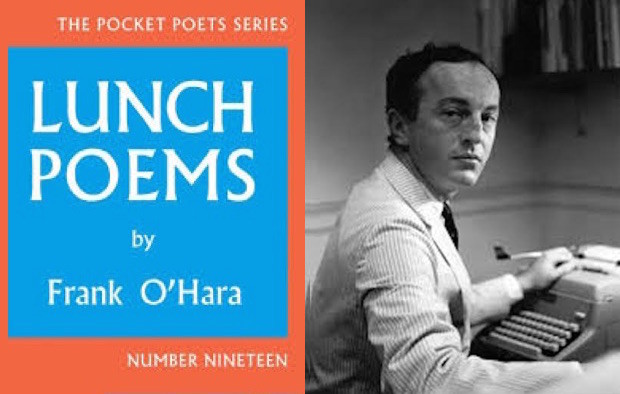

In Michel De Certeau’s classic essay “Walking in the City,” he describes walking as composition and argues that walkers’ “bodies follow the thicks and thins of an urban ‘text’ they write without being able to read it.”[1] Frank O’Hara’s 1964 collection, Lunch Poems, produces a textual account of his speaker’s walking, an account that queerly articulates the city by means of the presences and absences of what he pays attention to and records. O’Hara’s city in the poems is a queer assemblage created by his speaker (who is commonly read as O’Hara), out of his quotidian procedures of moving through and “writing” the city by compiling what he sees into a gloss on what his city is. The assemblage of the city written by O’Hara’s walking speaker, and composed by means of what I refer to as his “queer attention,” posits the city as a space that expects and produces heterosexual object choice that O’Hara resists as he compiles the city against its straight grain.

O’Hara’s queer engagement with the city suggests that a parapatetic relationship to high-use streets is a productive illustration of the affordances of queer space and time as Jack Halberstam describes them in the introduction to In a Queer Time and Place; Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives. Halberstam writes, “By articulating and elaborating a concept of queer time, I suggest new ways of understanding the nonnormative logics and organizations of community, sexual identity, embodiment, and activity in space and time.”[2] Reading O’Hara’s engagement with Manhattan as it appears in Lunch Poems as a queer articulation of time and space affords him a means in the poems of revising, refusing, or embellishing the sensory experience of the city’s streets. Against the text of the city that he follows as he walks, O’Hara composes another, queerer text in the poems that selects from what he noticed (or imagined) as he moved through the city. The poems are not only an overlay of the lived city on the planned city, but also figure O’Hara’s experience of the city as a refusal of its social and spatial systems.

There are a number of features of Lunch Poems that belie the speaker’s queer attention. One is O’Hara’s inclusion of imagined spaces (cities he has never visited, scenes that may never have happened), what John Ashbery refers to in the introduction in figuring the book as “a marvelous half-fictive universe” and the poems as “speculative rumination.”[3] A second is the framing of these poems as written at lunch, in a gap between workday and workday. By writing the poems on his lunch break (or purporting to), O’Hara produces his most important work during his nominal nonworking time, reversing the exhortations of capital to spend the workday producing and its periphery in consumptive leisure. A third feature is the expectation of movement, of the poems taking place while walking in the city, representing an experience that De Certeau argues should be unreadable to its producer. The book’s first poem, “Music,” opens with the possibility of a pause, as though in O’Hara’s stride, “If I rest for a moment near The Equestrian / pausing for a liver sausage sandwich in the Mayflower Shoppe.”[4] The book begins in the act of walking. While few of its poems are actively peripatetic, there is the expectation of walking as the premise of the poems. O’Hara cites walking as his default midday activity; it’s what lunch is for O’Hara, in addition to (or sometimes in place of) a meal. For instance, “Personal Poem” opens, “Now when I walk around at lunchtime.”[5] These are poems framed as being written before, during, after, or instead of walking.

The speaker’s movement through the city creates an assemblage of what he sees, thinks about, tastes, imagines, touches, remembers, smells, and hears that establishes his lunch hour as queer time, set against the straight expectations of the workday. As Jack Halberstam defines queer time, he acknowledges that it is about compression and annihilation but “it is also about the potentiality of a life unscripted by the conventions of family, inheritance, and child rearing.”[6] O’Hara’s observations identify his pleasures and concerns, and separate him, a gay man in his thirties, from attention to children and family. In the poems, he offers accounts of noticing and often objectifying men, frequently men of color, visiting with friends, remembering and imagining other moments and places, and spending money haphazardly on cigarettes, alcohol, periodicals, cheeseburgers, milkshakes, and juice. O’Hara’s movement through the city exemplifies what De Certeau argues of walking, that “[t]o walk is to lack a place.”[7] The place that O’Hara lacks is one of legibility within the systems of compulsory heterosexuality, a lack that on his lunch hour becomes an asset to the poems. The poems “A Step Away from Them” and “The Day Lady Died” illustrate this queer attention.

In “A Step Away from Them,” O’Hara offers a set of objects that are valuable by virtue of being the ones he selected. On his lunch hour, O’Hara peripatetically consumes the visual and tactile information of the street, recording fragments of it in the poem. The opening stanza reads,

It’s my lunch hour, so I go

for a walk among the hum-colored

cabs. First, down the sidewalk

where laborers feed their dirty

glistening torsos sandwiches

and Coca-Cola, with yellow helmets

on. They protect them from falling

bricks, I guess. Then onto the

avenue where skirts are flipping

above heels and blow up over

grates. The sun is hot, but the

cabs stir up the air. I look

at bargains in wristwatches. There

are cats playing in sawdust.[8]

O’Hara notices men on the street, likely shirtless (as their torsos are “dirty” and “glistening,” as though showing sweat on skin, not fabric). Although it’s his lunch hour, it’s the men who are eating and not O’Hara, who is instead consuming the city’s visual data. And yet he indicates that his walk is a part of his definition of lunch — a meal and/or a walk — by linking the walking clause to the opening clause via the conjunction “so,” suggesting the start of a logical sequence. He walks from the “sidewalk,” perhaps a numbered street, to the “avenue.” While it is unlikely that he is walking in the street, (he is looking at bargains in wristwatches, which are either in shop windows or being sold on the sidewalk) being on the larger street suggests that its busyness makes it feel like a thoroughfare, perhaps too busy to fit in O’Hara’s definition of a sidewalk.

On O’Hara’s sidewalk, there are no women or children. On the avenue, there are no people at all (just disembodied skirts and heels). O’Hara’s Midtown Manhattan in “A Step Away from Them” draws a counterpoint to the expectation that it is busy, full of people. In writing the city, he gets to edit out everyone with whom he does not want to share the street. He records a kind of duplicated writing of the city, writing it once by moving through it and noticing selectively, and writing it again in the poem. In Halberstam’s articulation of queerness, he suggests that it can open up “alternate relations of time and space.”[9] O’Hara’s revised avenue produces his alternate record of the time and space of Midtown. In walking, he participates in a fantasy of the city. He steps out into a busy network of urban streets, and yet this stepping out is framed by the refusal of the title, the step away from the normative “them” of the workplace, or the city’s heteronormative populace, that writing the city affords.

Like “A Step Away from Them,” O’Hara’s “The Day Lady Died” is also as a peripatetic poem. It presents O’Hara’s afternoon errands, in advance of following a rush-hour commute, from city to suburb, to arrive for dinner at the house of strangers. The final two stanzas read:

and for Mike I just stroll into the PARK LANE

Liquor Store and ask for a bottle of Strega and

then I go back where I came from to 6th Avenue

and the tobacconist in the Ziegfeld Theatre and

casually ask for a carton of Gauloises and a carton

of Picayunes, and a NEW YORK POST with her face on it

and I am sweating a lot by now and thinking of

leaning on the john door in the 5 SPOT

while she whispered a song along the keyboard

to Mal Waldron and everyone and I stopped breathing[10]

In advance of this trip, O’Hara purchases a series of items to bring from Manhattan to Long Island. He plans to take a commuter train (the Long Island Rail Road goes from Manhattan to East Hampton) that he will share largely with people at the end of their workday, who are traveling back to Queens or various points on Long Island where they live.[11] Whether or not those people are parents or are themselves heterosexual, the procedure of the commute puts O’Hara on the train of compulsory heterosexuality, from a site designed for commerce and economic activity, to one designed for heterosexual couples and their children to live in single family homes. In seeing the newspaper that contains Holiday’s face and death announcement, O’Hara shifts the location of the poem from the tobacconist’s shop to the club, and from the present to the past. It is in this final turn that the poem becomes fully populated. O’Hara has again been moving through a busy urban space, but has not mentioned any groups of people, only individual shopkeepers or bank tellers. In the final line, he is part of an elected community (the people who have chosen to be in the club to hear Holiday sing) rather than the incidental community of commuters or people using the street. He stops moving to look at the newspaper and reinforces his stillness by remembering leaning against a bathroom door (a site of queer sex, as well as another step away from the them of the club), giving the infrastructure his weight. The fixity of standing in one place is juxtaposed both against his prior movement and against the movement of the city at rush hour, earlier in the poem. This past moment is more somatic to O’Hara than the present, and more collective. His refusal of normative, linear time (he moves from embodying the present to embodying the past, from rushing to being still, from being alone in the city to being part of a collective in the club) requires the collaboration of the content of the poem and its form, which closes with a stress at the end of the reader’s long breath, leaving them, like O’Hara, winded and still.

Reading O’Hara’s work as participating in a queering of the space and time of Midtown Manhattan can offer a map for reading how other poets shift the spatial and temporal expectations of what cities are and how they can be experienced. While Halberstam locates queer time as arising out of the AIDS crisis, from the experience of being in the “shadow of an epidemic,” he expresses that it is necessary to move beyond a sense of queer time that is only foreclosure rather than affordance.[12]

O’Hara uses his refusal of normative time and space to select the aspects and moments within his urban life in which he most wants to exist. As he moves through the city, he creates a counter-city, which he distills in his poems. The city that appears in the poems is what De Certeau refers to as “[a] migrational, or metaphorical, city,” which “thus slips into the clear text of the planned and readable city.”[13] These features of the city are presumed unreadable in part because use happens in time, whereas planning is fixed in time, always in the act of imagining the future of the city. But in writing the poems, O’Hara gets to pause the city as it moves, the way his speaker is paused in his movement by the newspaper. Using the city overloads its present. It creates a “now” that is in a continuous state of ending before it is visible to the user. Comparing the metaphorical city to the planned city suggests that both are partial, one slipping into the other. In that slippage, a queering of space and time is an integral feature of how people use the city and of records of urban space in the process of being used. Following O’Hara, the city’s use can provide a queer contrast to its planning, and extend its queer form both within and beyond the lives of queer people.

1. Michel De Certeau, trans. Steven F. Rendell, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 93.

2. Jack Halberstam, In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives (New York: New York University Press, 2005), 6.

3. Frank O’Hara, Lunch Poems (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1964), viii.

11. The fact of this being a workday is indicated by the death of singer Billie Holiday, as referenced in the poem’s title, which occurred on Friday, July 17, 1959.

Queer Urban Poetics