An interview with William J. Harris

PennSound podcast #49, with an introduction by Harris

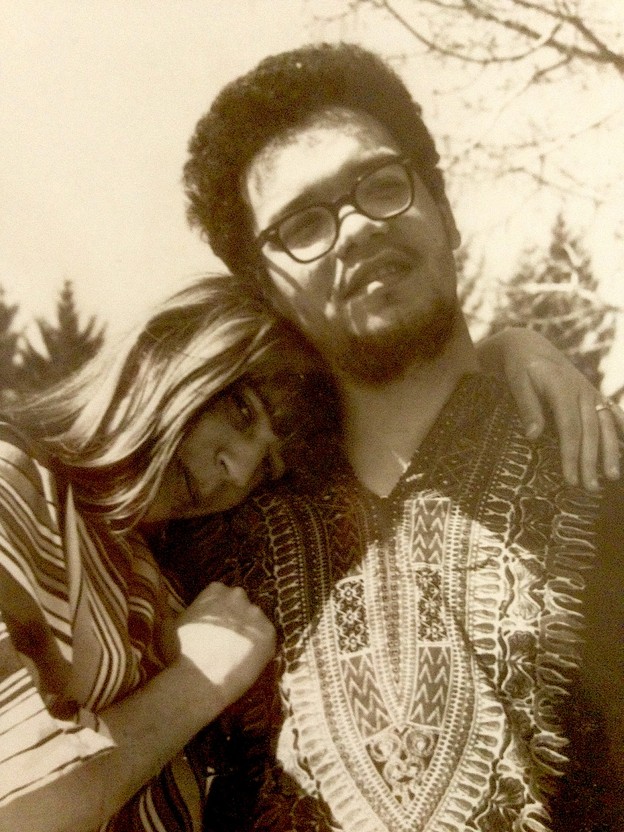

This interview tracks my genesis and early development as a poet and intellectual. My artistic and cultural education occurs during the late ’50s, the ’60s and the early ’70s and takes place primarily in and around academic institutions: the liberal college, Antioch, which is in my hometown of Yellow Springs, Ohio, and the nearby black state university, Central State, in Wilberforce, and the story, if not exactly concluding, comes to “a momentary stay against confusion” at Stanford University in Northern California where I did my MA in creative writing and a PhD in English.

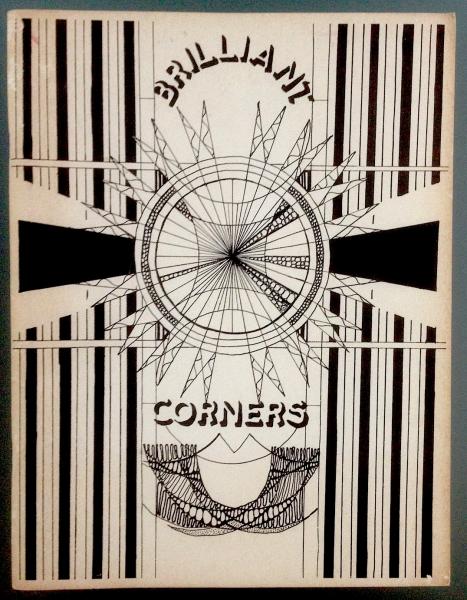

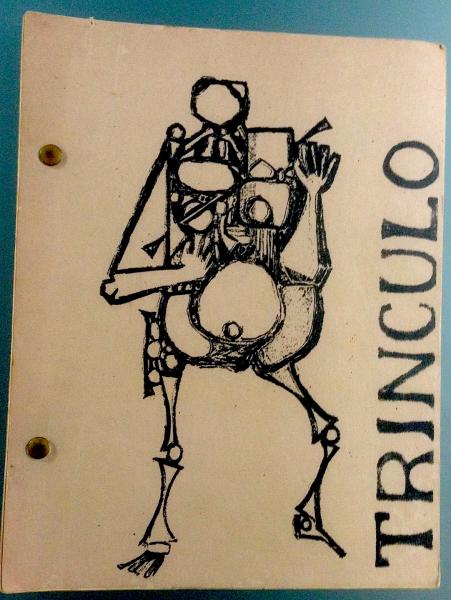

My main education came mostly from students, not professors, because the students were in contact with what was happening in the culture. This was the time of the New American Poetry, the postwar avant-garde movement, and free jazz, the radical new black music. Even though I was not a student there the students at Antioch and what I read there taught me about the New American Poetry and at Central I learned a little about free jazz. Well, heard it anyway. Listening to it with a group of black militant students, I found it incoherent; they didn’t. It would take me years to make sense of it. Also at Central I met the future black philosopher Leonard Harris — no relation — who not only became a prominent black philosopher but was one of pioneers of the emerging field of black philosophy. At both Antioch and Central I edited student literary magazines, Trinculo at Antioch and Gem at Central. At Stanford my understanding of the New American Poetry and experimental writing deepened: not only by my talking with fellow students and Al Young but also by meeting the black novelist, Ishmael Reed. There I was associated with the black student magazine, Brilliant Corners, named after a Thelonious Monk tune and edited by Bob O’Meally, an undergraduate. Among others it published Nate Mackey, Robert Stepto, Al Young, Jon Eckels, Johnie Scott and me.

Even though I had wonderful teachers, including the poet Wendell Berry, the modernist poetry scholar, Al Gelpi and poet-critic Donald Davie, once again most of my real schooling came from the students. Nate Mackey, now a major poet, Bob O’Meally, now a major jazz scholar, and the amazing Al Young taught me about jazz. Al wasn’t actually a student but a Jones Lecturer, a teaching fellow at Stanford, but he hung out with us. As important to my jazz education as these folks was one book, Amiri Baraka’s Blues People, which I read in 1967 in Yellow Springs simply because I was reviewing it for the liberal journal, The Antioch Review. It became my bible and I knew it well before I knew the music well. My Stanford friends helped complicate its story. At Stanford my understanding of the New American Poetry and experimental writing deepened. Not only by talking with fellow students and Al Young, but also meeting the black novelist Ishmael Reed. Al Young being our literary ambassador had introduced us to him. After hearing Reed read I remember a fellow black graduate student — I think, Fred Johnson — say, “I want to write like that, not like Richard Wright. I am sick of naturalism.” Ish opened up new worlds for us. And so did his experimental multicultural lit magazine, Yardbird Reader. “Yardbird” is the nickname for famous bebop saxophonist, Charlie Parker. (The journals’ titles, Brilliant Corners and Yardbird Reader, reflect the centrality of the music to the literature.) The Reader published such people as Jeffery Paul Chan, Amiri Baraka, Nate Mackey, Anne Waldman, Jay Wright, Simon Ortiz, and me. Reed was from that other world — Berkeley — where black writers wrote wild stuff and college students got involved in tear gas-filled uprisings. I hope my encounters with these times, the shifting social and political attitudes, the people, the New American Poetry, the New Black Writing, bop, post-bop and free jazz, will throw some light on them for both me and the listener. I certainly wasn’t the center or at the center, but I have lived through some important cultural and social moments.