'A grand collage'

A review of 'A Jerome Rothenberg Reader'

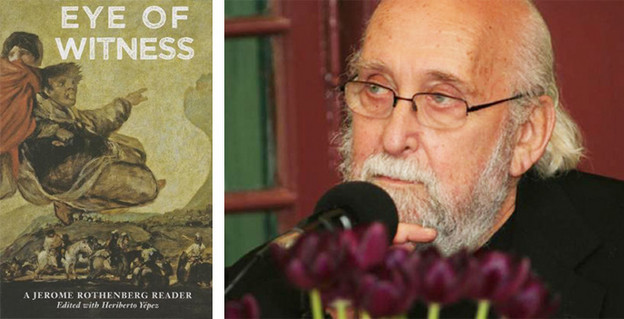

Eye of Witness: A Jerome Rothenberg Reader

Eye of Witness: A Jerome Rothenberg Reader

Published by Black Widow Press as part of their Modern Poets Series, Eye of Witness: A Jerome Rothenberg Reader interweaves poems with prose work in a grand collage,[1] proffering a vivid map through the intellectual and procedural frameworks of Rothenberg’s oeuvre. Eye of Witness traces a cogent, compelling narrative of an extraordinary and extraordinarily large, diverse body of work, synthesizing for us the poet’s mind at work across sixty years of poetic endeavor.

A feast and a surfeit, this collection, edited by Heriberto Yépez and Rothenberg in collaboration, tracks Rothenberg’s work along with the evolution of the poet’s sense of his project. Eye of Witness’s braided timeline, layering old with new, first insights and later renewals and revisions, conveys to us a poet-navigator, always looking to the future, his boat drawn with him, a vessel deep-loaded with the riches of the past, provoking for us the experience of the fabulous within the mundane ground of the living world. Eye of Witnesschallenges the reader to question how might we, beautiful and terrible as we are, live in this beautiful and terrifying world — how does language return us to it and it to us? Affirming the potency of the other-than-human world to human understanding and experience, Rothenberg asserts “the poet’s work may, like the shaman’s, make its encounter foremost within language — may start with language and use that as a vehicle with which to drive toward meaning, toward a (re)uniting with the world’” (Rothenberg citing Eliade, 171).

In his introduction, Heriberto Yépez provides valuable insights into the long and complex evolution of Rothenberg’s poetics, tracking the move Rothenberg makes from Deep Imagist to shaman-as-poet, to trickster as generative mythos, and ultimately, to the figure of witness, this long process invested in what Yépez terms “a call for the simultaneous renewal of cultural forms and a reconfiguration of consciousness, a matter of making new cultural and spiritual constellations available” (19). Yépez further asserts: “Rothenberg’s witness is the marker of a new kind of poet — its pre-face — in which two apparently opposite drives coexist: an acknowledgment of poetry as a perpetual and radical change of form — and thus the willingness to not retain any-thing — and a desire to construct a total poetics, or — to use a recent word of Rothenberg’s — an omnipoetics: to say in every form possible what cannot possibly be said” (23). Indeed it is the witness to which this book owes its title, a witness who “still belongs to the oneiric dreamworld but is plagued by the human capacity for cruelty” (22). This collection of Rothenberg’s work vividly illustrates, across a multiplicity of genera and forms, the revelations of the dreamworld, what it teaches us about the human capacities for beauty and horror, and the collateral wonders and terrors our human capacities provoke.

While Yépez tracks a journey or evolution, Rothenberg’s intention in the collection is to “assert a wholeness in the work” (24); both of these insights are manifest in the gathering. Rothenberg and Yépez weave newer poetry with older prose, and vice versa, as well as layering into the mix performance pieces, plays, sound work, translations, variations, and extensions. The proses themselves are diverse, including letters, manifestos, lectures, a response to Harold Bloom’s critical apparatus, prefaces and postfaces from Rothenberg’s books, et cetera. Throughout the collection, Rothenberg asserts the collaborative/collective nature of poetry, “an exploration of what our poetry could be — what we could make it to be — as an art of sound and gesture” (26). Rothenberg positions his translations and total translations, his variations, texts for performance, and his plays, as integral to his “pursuit of a kind of transcultural or global poetics, rooted in place but capable of crossing borders and languages to become a virtual omnipoetics” (26). Rothenberg conceives (his) poetry as a collaborative venture with other poets and language workers, translation as a process resulting in new texts, in which “discovery at every point I meet the poem” (56) is operant. In keeping with that aesthetic and ethical modus operandi, Eye of Witness juxtaposes excerpts from 50 Caprichos After Goya withvariations on Octavio Paz’s “Blanco,” a translation of Picasso’s “The Dream & Lie of Franco,” and translations of two of Tzara’s Dada poems (“A Book of Otherings”); or later, excerpts from a prepared talk on the poetics of the sacred, meditations on ethnopoetics, and an essay, “Primitive & Modern: Intersections & Analogies,” with a discussion of the relation between poets and the trickster figure (included in “Poetics & Polemics 1: Toward an Ethnopoetics”). In “A Book of Extensions,” translations from Seneca songs stand shoulder to shoulder with Rothenberg’s collaborations with visual artists (Tom Phillips, Susan Bee), his photo-text collages, his play “Esther K Comes To America: 1931” a series of verbal translations of events and rituals, and excerpts from his collection That Dada Strain in which Dada and jazz both serve as instigations. Much like the anthologies for which Rothenberg is renowned, Eye of Witness is structured as assemblage and collage, lending to anthology the same attentions given to the making of poetry.

Organized into three “Galleries” and three “Poetics & Polemics” sections, as well as “A Book of Otherings,” “A Book of Extensions,” and “New Poems: Divagations & Autovariations,” Eye of Witness takes its reader from early translations from German and Rothenberg’s originatory work with Deep Image through his translations of Native American traditional texts and the formulation and extension of Ethnopoetics to his secular (re)encounters with Jewish mystical traditions and his European Jewish heritage, the aftermath of the Holocaust and the possibility for and requirements of a poetry post-Holocaust (the fundamental function of the poet as witness),[2] and into the vision of an omnipoetics in which the “challenge of a poetry & a counterpoetics is as much needed as ever”:

the matter of the revolutions of the word & how they might exist today … the internet, the web, offers a new arena for visual, performative, & interactive modes, moving (sometimes at least) in multiple cultural directions. The number of such websites & displays is in fact enormous, so that watching the experimental work already triggered — the technical ease in its construction — there’s a sense, isn’t there, of a futurism that has come into its future … what I’ve more recently come to call an omnipoetics. (547–48)

What stands out to this reader? So much that I may only hint at the astonishing riches awaiting Eye of Witness’sreaders. For the world of familial and cultural origin — that vexed place of hunger and poverty, of otherness and oppression, of war and ruin, demons and executioners — an excerpt from “The Wedding” (Poland/1931):this music, this urgency, this terror.

we have lain awake in thy soft arms forever

thy feathers have been balm to us

thy pillows capture us like sickly wombs & guard us

let us sail through thy fierce weddings poland

let us tread thy markets where thy sausages grow ripe & full

let us bite thy peppercorns let thy oxen’s dung be sugar to thy dying jews

o poland o sweet resourceful restless poland

o poland of the saints unbuttoned poland repeating endlessly the triple names of mary

poland poland poland poland poland

have we not tired of thee poland no for thy cheeses

shall never tire us nor the honey of thy goats

thy grooms shall work ferociously upon their looming brides

shall bring forth executioners

shall stand like kings inside thy doorways

shall throw their arms around thy lintels poland

& begin to crow (215)

Or Rothenberg’s “Cokboy,” a punning, musical, and satiric mashup of the disparate elements of the American mythos: a wandering Jewish mystic in the American wilderness (the “wild” west), speaking with a Yiddish accent in nonsense vocables and plain English among a heterodox company, including the Baal Shem (later reborn as a beaver, Rothenberg’s Seneca totem lineage), cowboys like “the financially crazed Buffalo Bill,” Custer, and Barry Goldwater (“a little christian schmuck”), Native Americans, “Polacks,” the Cuna nele, prospectors, Anglo Saxons, and Lao Tzu all in kabbalistic time “like Moses in the Rockies,” until like any storyteller, Rothenberg winds down his tale into silence from within which we ponder this “America disaster”:

I will fight my way past you who guard the sacred border

last frontier village of my dreams

with shootouts tyrannies

(he cries) who had escaped the law

or brought it with him

how vass I lost tzu get here

was luckless

on a mountain & kept from

true entry to the west true paradise

like Moses in the Rockies who stares at California spooky in the jewish light

of horns atop my head great orange freeways of the mind

America disaster

America disaster

America disaster

America disaster

where he can watch the sun go down

in desert

Cokboy asleep (they ask)

only his beard has left him

like his own his grandfather’s

ghost of Ishi was waiting on the crest

looked like a jew

but silent

was silent in America

guess I got nothing left to say (242)[3]

Or Rothenberg’s polemic of a visionary and revolutionary poetics posited against Harold Bloom’s privileging of repression over freedom, challenging that critic’s “Scene of Instruction, which is necessarily also a scene of authority and priority” in which “the true poem is the critic’s mind” and all poetry reducible to “the inescapable anxieties of competition” (405, 402, all quoting Bloom), a system of “mis-reading [and] deception” (405) in defense of a canon “European … post-Enlightenment & English” (406). To which Rothenberg incisively and rigorously responds:

But we know, after all, who threatens us. We know who reminds us of how 'heavy' our 'inheritance' is; who tells us not to deign to be good readers of our own poems or to think that we can write at all 'after the deluge'; who enters in Milton’s Shadow — & 'not the Romantic return of the repressed Milton' but the Puritan Milton of repression. And we know who proposes the discontinuities between poets & rejects those who might know their lineage too well. We know who thinks that he 'can block a new voice from entering the Poet’s Paradise' or who would presume 'to help decide a question that is ultimately of sad importance: ‘Who shall live?’'(416)

Rothenberg asserts that it is not Blake’s “Devourer” (here Bloom) but Blake’s “Prolific,” the poet of “the unqualified ‘freedom’ of the Romantics & their successors” (403), “the forwardness that has again & again defined an avant-garde over the last two centuries” (406). Rothenberg asserts, “The game, in short, is up … [and Bloom doomed to his own summation of the Cherub’s fate]: ‘He cannot strangle the imagination, for nothing can do that, and he in any case is too weak to strangle anything’” (416).

Or the astonishing beauty and terror of “Fourteen Stations,” Rothenberg’s responses to Arie Galles’s monumental charcoal drawings of aerial views of the Nazi concentration camps and the horrors they represent: “Fourteen Stations”/“Hey Yud Dalet.” The poems are composed by means of a procedure using Gematria counts from “the Hebrew and/or Yiddish spelling of the camp names … keyed to the numerical values of Hebrew words and word combinations in the first five books of the Bible … not so much to mask feeling or meaning as allow it to emerge” (433):

The First Station: Auschwitz-Birkenau[4]

now the serpent:

I will bring back

their taskmasters

crazy & mad

will meet them

deep in the valley

& be subdued

separated in life

uncircumcised, needy

shoes stowed away

how naked they come

my fathers

my fathers

angry & trembling

the serpents

you have destroyed

their faces remembered

small in your eyes,

shut down, soiled

see a light

take shape in the pit,

someone killed

torn in pieces

a terror, a god,

go down deeper (434-4)

Or this total translation from the oral to the page as concrete poetry, work done in collaboration with Richard Johnny John: “Songs From The Society of The Mystic Animals” of the Seneca (323).

As vivid as this translation is, his performance of it is something else entirely, returning to it music and rhythm, the breath of the body, and the sound of the rattle: both the visual and performed versions transforming our understandings of poetry.

And finally, I offer the reader, from “A Poem of Miracles,” this “Coda,” dedicated to Diane Rothenberg:

A miracle

the unseen

overtaking us

the larger world

in darkness

darker than the mystery

of birth

the miracle resides

in what we see

& touch so good

to be here

& to bow to you

my dearest friend

in darkness

as the poet said (575)[5]

Here, what has always glowed so warmly in the heterodox and radically revolutionary work of Rothenberg, is a deep humanity and love.

For the reader who has yet to encounter Jerome Rothenberg’s work, Eye of Witness offers a wide-ranging entre into his rich and omnifarious oeuvre, a vital space of revelation for lovers of language and poetry. For the reader already familiar with Rothenberg’s phenomenal endeavors, Eye of Witness affords synthesis and a retrospective view of his writing’s evolution, delivering a clear sense of the wholeness of that diverse, multiform work and its generative impulses and sources, the work of one of the great minds and poets of our time, perhaps of all time. An homage to an extraordinary language worker, a poet dedicated to the renewal of language and of our encounter with the world, Eye of Witness is itself an extraordinary document and an essential companion for poets and critics seeking an understanding not only of Rothenberg’s work but of the progress of visionary language work from ancient times to the present as it has unfolded via recuperation, discovery, and (re)invention from the late nineteenth to the early twenty-first centuries, a poetry Baedekker for us all. Kol ha kavod, Jerome Rothenberg and Heriberto Yépez!

1. Rothenberg’s term for “the life of poetry.”

2. “I am a witness like everyone else to [the world, the present, as it comes and goes], and all the experiments [the poems] for me … are steps toward the recovery/discovery of a language for that witnessing” (391).

3. Listen to PennSound recordings of Rothenberg reading part 1 and part 2 of “Cokboy.”

4. Listen to a PennSound recording of Rothenberg reading “The First Station.”

5. Listen to a PennSound recording of Rothenberg reading “A Poem of Miracles.”