My preferred pedagogy is 'Pathetic Literature'

Pathetic Literature

Pathetic Literature

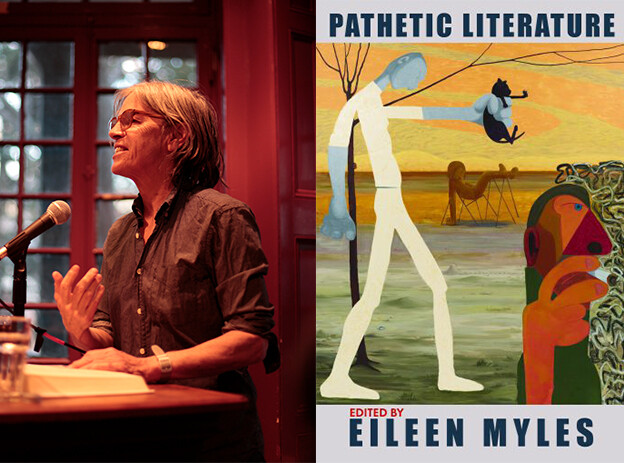

A stingray doesn’t know the word for “pathetic.” A saint does not care if prayer renders her pathetic. Poets are pathetic because they devote themselves to form in the face of formlessness. (Are they? Do they?) These kinds of formulations and queries arise in reading Pathetic Literature, the momentous anthology edited by Eileen Myles and released by Grove Press in November 2022.

Myles’s introduction to Pathetic Literature begins with a declaration that “literature is pathetic.”[1] If all literature is pathetic, then Myles’s title becomes a kind of tautological half-joke. But tautology opens the door to a useful problematic, or maybe just a pedagogical gesture. The genre of “pathetic literature” takes its origins from a syllabus constructed for a seminar Myles taught at UC San Diego in 2006. That Myles’s designation of “pathetic literature” emerged in an explicitly pedagogical and institutional context should guide our reading of the anthology. Pathetic Literature collects “Work that acknowledges a boundary then passes it,” as Myles writes in the introduction. “‘It’ being the hovering monolith, that bigger thing that confirms. There’s no institution, or subculture, where any of this all belongs” (xv). That makes for a knotty task: what does it mean to anthologize, or institutionalize, the pathetic, given the genre’s roots in institutional critique or the rejection of institutions?

This question appears in the contributions of both Sei Shōnagon and Sergio Chejfec, who consider — or challenge — the relationship between allegedly private composition and the public sphere. In his excerpt from Notes Toward a Pamphlet (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2020), Chejfec writes of an imagined Argentine writer, Samich, “who, while he inhabited the world, aspired to a voice permanently lowered, would, paradoxically perhaps, require the megaphone a pamphlet represents in order to have his ideas, or whatever they’re called, disseminated” (525). Chejfec’s Notes Toward a Pamphlet is “pathetic” for its decision to dwell in the process of writing: it’s not even a mere pamphlet but notes toward one. It prioritizes “elliptical” behavior and practice, in Chejfec’s own words, over arrival. Chejfec also embraces the pamphlet for the way it simultaneously occupies the “low,” or ordinary, while publishing or distributing one’s language to a large reading public. And it leads us to one of Myles’s central questions: what happens when the little one — the worm-ridden, minor, unpopular, queer literature — becomes a tome? What do we make, in other words, of Myles’s megaphone by way of anthologization?

The anthology, featuring the likes of Chantal Akerman, Saidiya Hartman, Dennis Cooper, Kim Hyesoon, Chester Himes, Etel Adnan, Simone Weil, Fred Moten, Victoria Chang, and Violette Leduc, surveys literature in English and translation that sing of small battles against large institutions including the church, Reagan administration, university, English grammar, and the Office of the New York Mayor. We observe the bestiary of creatures in Pathetic Literature, like Laurie Weeks’s worms or Samuel Beckett’s orange pomeranian in Molloy or Marcella Durand’s ant colonies, but perhaps Pathetic Literature is most radical or compelling as a fulfillment of Charles Bernstein’s 1992 call to revolt against what he termed “frame lock.” The anthology is a thrilling resistance to the “frame-locked prose [which] seems to deny its questions, its contradictions, its comedy, its groping.”[2] I likely find myself calling Pathetic Literature a textbook, when not a desert-island book, because I believe it offers a political and aesthetic education on institutions through the act of questioning the relationship between literature, experimentation, and institutionality.

“Sweet invocation of a child, most pretty and pathetical,” says Armado in Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost.[3] Armado utters the phrase after the character Moth addresses him in a finely poised line of words. Armado’s usage of “pathetical” is before pathetic meant “mean,” in Myles’s words, before it fell from grace; the editors of my Shakespeare edition, Bate and Rasmussen, gloss “pathetical” as “moving.” Given Love’s Labour’s Lost is a play about language, a lot of the comedy of Shakespeare’s play lies in the pathos, and pathetic disposition, that emerges from attending to one’s diction too much. Armado is pathetic here for his compulsion to parse good phrases.

Why does one parse good phrases? Sometimes, it’s to have something fun to rattle around in your mouth, but it’s also for survival. That most explicitly comes across in Karla Cornejo Villavicencio’s “New Haven,” a lengthy and electric prose entry in Pathetic Literature. Cornejo Villavicencio’s essay, combining autoethnography and sharp wit, explores the grueling nature of life and healthcare for undocumented immigrants, such as the author’s parents, in the US. We witness similar modes of compositional urgency in Baha’ Ebdeir’s prose on Palestine and Brandon Shimoda’s contribution on Hiroshima and the Tohoku earthquake. Cornejo Villavicencio’s essay, too, shares the skepticism with which Rebecca Brown writes on AIDS, unsure whether it’s worse when writing succeeds or fails at narrating pus and sores and whom it satisfies. Brown’s contribution, along with Joe Westmoreland’s account of contracting HIV, reminds us that “AIDS is a lot of the reason for this pathetic book,” as Myles writes in their introduction to the volume (xix). AIDS is a locus at which we can identify what Myles and their collaborators mean by pathetic: moments when the failures of the body to comply with institutions remind us of the failures of language. We continue to respond with a lowercase poetics anyway. We learn, Myles suggests, that doing so serves a vital function.

To raise the question of a pamphlet within an anthology, as Chejfec does, is a way to ask about scale. Myles, along with the anthology’s slew of authors, defines their pathetic literature against the “monolith” of numbers and big data. “You cannot see the numbers she cites without feeling that something must be done, while also feeling dwarfed by the scope of things,” writes Matthew Stadler on sociologist Saskia Sassen’s research on citizenship and statelessness, and that’s maybe what I mean here (370). “Statistics cast their spell,” Stadler continues, so we feel forced to take up techne. “I know this about myself: I’m not porous enough, big enough, small enough, to fit through the hole of the next hour,” Camille Roy writes in her brilliant, diaristic “Reading My Catastrophe.” “It’s the rollercrasher” (68). I like to believe Roy means this here — writing — is the resistive rollercrasher.

Ellipses repeat in the anthology as sly exceptions to the laws of scale. “Here are some uses of ellipses,” Chris Kraus interrupts as she and Dick begin to kiss in an excerpt from cult classic, I Love Dick (113). Or, poet Renee Gladman writes, “M.’s ellipses,” drawing attention to Monique’s speech earlier on the page cluttered with ellipses that we may have glanced over (462). Elliptical moments are antistatistical as well as distinct to their textual contexts. But ellipsis, too, has loftier goals: Chejfec describes his fabricated poet, Samich’s, “elliptical” behavior, that “he did not publish in order to preserve his ellipsis from any potential threat or form of critical surveillance” (522). An anthology, in many ways, is the best way to preserve ellipsis. It’s rare to read it all the way through or ever reach an “end” but instead requires renewal.

Layli Long Soldier’s poem “38” in the anthology derives its strength from its invocation of scale — or interest in the politics of the sentence versus politics of the nation. Long Soldier undertakes linguistic and syntactical experimentation in response to the grammar constitutive of the displacement and genocide of Indigenous people. She reminds us why exactly she has elected to focus on the scruples of syntax and diction: “I’ve had difficulty unraveling the terms of these treaties, given the legal speak and congressional language” (303). Judy Grahn’s “A Woman Is Talking to Death” utilizes the form of testimony to, in Myles’s words, “enclose an entire world, all its institutions, in a single poem” (xiv). Midway through the poem, Grahn describes being a “pervert,” by which she means attempting to save an Asian woman who is brutally attacked by a cab driver (261). In calling the police, Grahn describes, “Six big policemen answered the call / no child in them. / they seemed afraid to touch her, / then grabbed her like a corpse” (261, emphasis in original). It’s reminiscent of Tommy Pico’s pronouncement in Junk, a text that would find itself at home in the anthology: “You should be accountable to what you touch.”[4] Or, as Precious Okoyomon writes, “If u touch it it’s yours / These are bonds / One thing next to another doesn’t mean they touch” (547). If touch renders Grahn pathetic or perverse in her commitment to empathy in the face of policing and the state, she is fine with that.

It’s not so much that we’re afraid “to read about different things,” Andrea Dworkin writes on the tyranny of grammar (and the authors in Pathetic Literature suggest), “but to read in different ways” (28). That also explains why Pathetic Literature might lean toward plagiaristic writers: almost like a little dog, sniffing at a bloated animal carcass, writers can’t help but circle around scraps of dead, or just raw, material. “People might call this mode of working plagiarism, or pathetic, since it seems to avoid the effort of invention or because it avoids the usual tools and workplaces,” writes Tim Johnson on his collaborator Mark So’s artistic practice, which involves copying down his reading notes into an exposition (572–73). “I bet the same people consider it pathetic to be involved in many kinds of work, and to avoid work as well,” Johnson concludes. Some will inevitably call it dogged and undisciplined, but as Kathy Acker writes in her excerpt from Great Expectations, “I would rather be petted than be part of this human social reality which is all pretense and lies” (299).

“Good” writing remains a thorny question in Pathetic Literature and specifically in the post-internet era. When I wrote the line “Misery is trag,” for instance, in a poem last year, I was likely trying to sound pathetic. When I say I was trying to be pathetic, I mean that I was attempting to understand why the terms for my misery feel most pathetic when conveyed through an internet vernacular or why the motivation to articulate misery always feels pathetic altogether. When poet Andrea Abi-Karam writes, “public sex is @ a distance,” I laugh (289). Why? Because it reminds us, like Samuel R. Delany’s excerpt from Times Square Red, Times Square Blue in the anthology, that sex publics lack what they once did before the internet? Because it’s so obvious, pathetically so? Public sex in Abi-Karam’s poem is not just at a distance but @ a distance, which means it’s both closer and permanently mediated. It’s embedded. When Tom Cole writes, “I’m going to finish up all my projects that are computer based” in his excerpt from The Tyranny of Structurelessness, we laugh either because no one is going to finish up all their projects that are computer based or because we forgot it was possible to harbor such a desire (595).

“To render this poem’s ‘I’ as a bottom dweller was the best I could do,” Simone White told the Los Angeles Review of Books on composing “Stingray,” her ten-part poem featured in the anthology and among my favorite contributions, especially after hearing her reading of it at the anthology’s launch at the Museum of Modern Art in November (534–43). White’s analysis poses questions of value: Is there something pathetic in knowing, or admitting, one did “the best I could do?” That one’s “best” takes an animal form? (And a bottom dweller, at that.) I know describing misery as “trag” isn’t the “best” I can do, but perhaps pathetic literature’s task is to flip these value systems on their head. When sentences are crafted so well they required work, we know you worked at them. An admission of “giving your all” or emphasizing the effort involved in writing within the writing puts one at risk. Surplus of affect and labor all for a sentence. That’s likely why we hear teaching described as a pathetic profession. Every year, it is devalued by university administrations and the state. It is financially pathetic, it is commodified as small, resulting in a similar sort of affective surplus. Despite the ironic and humorous surface of the “pathetic” throughout the anthology, I wonder if another name for it might just be earnestness or, at its best, dignity.

A similar kind of earnest surplus characterizes Myles’s account of Cindy Sheehan who was called “pathetic” for waiting on George Bush’s street to talk to him after her son was killed in combat in Iraq. “The act of taking a little less or a little more,” Myles writes, “It’s the essence of political meaning” and how Myles defines the pathetic (xvii). The pathetic is a result of unmet attachments, either due to scale or economic abandonment or bureaucratic failure. Put another way, unmet attention or attachment leaves one with a surplus that I have learned to call the pathetic. In Playing and Reality, psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott describes an analysand who lived “from poem to poem (like cigarette to cigarette in chain-smoking).”[5] Winnicott’s analogy renders poem-reading a kind of compulsive, shame-inflicted act. It is performed out of desperation to formulate an attachment to daily life and to keep oneself occupied.

The act of writing, Pathetic Literature proposes, is perhaps the world’s most banal, low-risk endeavor with the highest capacity for psychic or political transformation. So, you text a friend every day but this time decide to type a few additional sentences for yourself? You break the line instead of typing a sentence in the way you typically do? I’m saying that the ability to work with the materials of language doesn’t require much deviation from the skills we use in our daily lives and can grant people agency or self-possession. It’s almost pathetically easy to make a sentence. But then you also want to be so good at it. I’m theorizing from my email server, from all my thrown-out scraps, from the things I wanted to forget, because that is writing. Pathetic Literature says so. “All my life,” to paraphrase Alice Notley at the anthology’s commencement, “I’ve been waiting” to hear it (1).

1. Eileen Myles, ed., introduction to Pathetic Literature (New York: Grove Press, 2022), xiii.

2. Charles Bernstein, “Frame Lock,” in My Way: Speeches and Poems (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 98.

3. William Shakespeare, Love’s Labour’s Lost (London: Red Globe Press, 2007), 316.

4. Tommy Pico, Junk (Portland: Tin House Books, 2018), 9.

5. D. W. Winnicott, Playing and Reality, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 2005), 84.