No form in mind

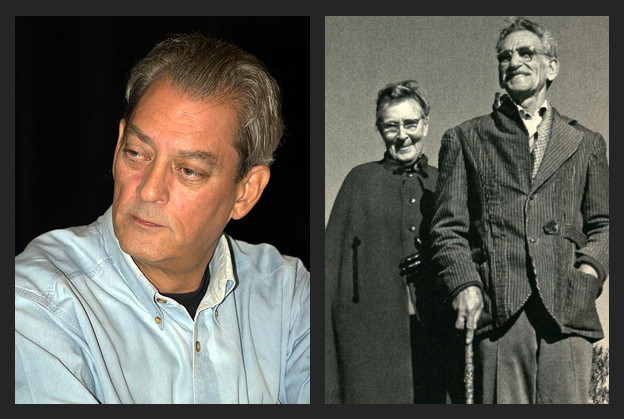

Paul Auster in conversation with George and Mary Oppen

Note: When Paul Auster in 1980 asked to interview his friend George Oppen, the poet agreed, but with a warning. “What worries me,” wrote Oppen, “is the question of whether or not I can say anything that I have not already said — And my own condition at this moment which is something alas, very like senility — I am not being very brilliant these days, and I have not written anything since Primitive.” Nevertheless, Auster flew to San Francisco in February 1981 and spent several days at the Oppens’ house on Polk Street recording George and Mary around their kitchen table. “There were times,” writes Auster, “when [George] had to grope for his words, but there were also moments of blazing wit, spontaneous remarks as precise and funny as anything I had ever heard him say.” These moments and many others, as the reader can now see, have indeed been captured in this memorable last interview with George Oppen. — Richard Swigg

Paul Auster: I think the first thing that struck me, reading through the poems, all of them all over again, is the constant appearance of the sea as an image. It’s in nearly every poem, and it seems to me that you use it as untamed nature itself, a fundamental given. It’s also important in the reference to Crusoe in “Of Being Numerous,” the shipwreck, and it’s important in your personal life, too, I know, having being a sailor for so long. I just wonder if you can think about it again — the presence of the sea in the poetry.

George Oppen: It’s also in the poem I wrote for Mary — mother and daughter and the sea. Like you say, I think it is important to me. It’s a symbol of space at least, and our native space. It’s some kind of stoppage, something you can’t go beyond, and it flows in upon you. We talked earlier about Reznikoff in those wonderful lines at the very end of Testimony, which does that. I think it’s marvelous, the way it could be done. It’s just naming the parts of the things, the names of things, in the order of chunks of substance. Just names, as far as one can think, it seems to me — the unlimitedness.

Auster: The unlimitedness. But it’s also a place that has no reference to civilization, really. Man doesn’t do anything there.

George: It is large, and it’s a freedom, and fear.

Mary Oppen: It was a great adventure, too. Then recently you’ve written this about Cortés, which is almost the opposite. Its aim is finding the limit, and finding in some way an exultation.

George: As a symbol of poetry, he’s lost, he’s discovered a continent. He’s absolutely lost and he’s elated. And I use the words as the working of poetry, the experience of poetry, to the nail. And perhaps to the reader, certainly to the writer. He moves beyond himself somehow or other, and he’s lost, and it’s a kind of euphoria for a moment in this state.

Auster: Going through the work, there’s another image that keeps cropping up — and I was dazzled by this. I had no idea — cars. Cars! From the beginning until the end. Cars in every other poem. I assumed you talked about them a lot, and again I was wondering what this meant to you — the image of the car, again and again the car.

George: It’s really there in my life. It’s my childhood. It’s my father who loved cars, and I probably —

Mary: You had a big car when you were eleven.

George: I had a car when I was eleven or twelve. But I’ve never known its meaning to me. I don’t know if I can reproduce it right now.

Mary: And George has been a magnificent driver all his life, and never liked anyone else to drive him. We used to drive just to drive, and George always did all the driving. When we were in Vincennes, down in Texas, they were reminding us that the four of us drove from Mexico into California, something like seventy-two hours straight, and George didn’t want anybody to stop him. He didn’t want anybody else to drive.

Auster: Well, it’s a very American thing. The car is a central part of American life in this century.

George: Yeah.

Mary: It’s our generation.

Auster: A defining force. But in the poems, what I feel is not so much a love of cars, as the isolating force of technology. A person gets into his car, and it’s as if he’s been given a new body made out of metal, and his body has become his mind. A ship and its captain, a body and its soul. It reduces people to monads. Isolated consciousnesses, walled off from one another.

George: I think I could say it’s not exactly love of the car. It’s love of myself, because there I am, flying down the street. It’s turned up in my life over and over again, including the army where they made me a non-com on the strength of it. It was a motorized unit. I was in charge of some of it.

Auster: In one of the later poems [“Route”] there’s an image of a man turned over in the wreck.

George: Oh, yeah.

Mary: And the wheels —

Auster: The wheels spinning, and “He doesn’t despair ... He sees in the manner of poetry.” Something like that.

George: We’re back again to — what’s his name? I just talked about him.

Auster: Cortés?

George: It’s the same thing. Any car is that thing, awfully grounded. Which is a very simple and common thing.

Mary: You have it in that poem “Enclosed in glass,” in the car [Discrete Series].

George: Yeah, that was a protesting against it. That was a recognition, too, about the car — [it] conceals somebody.

Mary: Concealed in glass, you said. “Enclosed in glass,” I mean.

Auster: There’s one poem, however, in which the car is presented differently. The early love poem about sitting in the Model T, and the car’s in the lake, walking home [“The Forms of Love”].

George: Yeah. Walking would have been more important than the car there. The car was just taking us there.

Auster: Again, these are things that startled me all over again, because I know the work pretty well. But the respect of woman, somehow: the nobility, alone in her courage. I was wondering if there was some kind of contract you set up between men and women, technology and consciousness. The women in the poems seem to embody a purer approach — something more akin to the way you feel about things than what you see around you. I was wondering if you had anything to say about that.

George: The women. I don’t know if this is what you’re thinking of. But I do remember I like the line, “And life seeming to depend upon women, and the knowledge of — ” [“Of Being Numerous”]. What did I say?

Mary: Bearing the burden of life.

George: “Life seeming to depend on women, burdened and / desperate” —

Mary: That was the line.

George: — which was before the women’s movement.

Auster: The men who appear here, the ones you respect the most, are craftsmen, people who build things, people doing careful work with their hands, both houses and … But other than that, not much. The other male figures who appear are usually quite alien, I think.

Mary: There’s the old man. “You are the last / Who will see him” [“Of Being Numerous”].

Auster: Yes, yes, yes.

Mary: And of course Pierre Adam in the war. No man had more respect than Pierre.

George: Yes, true.

Mary: The men that George mentioned, or other men that I know of in our lives, have been almost the purest type of craftsmen — Carlos in Mexico, as fine a man as ever was. Yet he isn’t in the poetry.

George: Yes, it’s true. And Mary about men. It’s just the degree to which men love Mary — what Mary can do to men.

Mary: Well, I like men very, very much.

George: It’s what you can do. You just include the men somehow — everything known between you and the people you’re talking to. One can’t say “motherly” because it’s something more than a mother would have. It’s respect in a way. The mother —

Mary: To care for them, to protect them.

George: We’re not as well-implemented as women.

Mary: Their faith.

George: Their faith.

Auster: In going through your work again, I’ve been trying to figure out why it feels different from other poetry. And my conclusion is, well, it’s the poetry of a grown-up. What we’re brought up with, in terms of poetry, is the Romantic tradition, which is a tradition of great egotism, of self-centeredness, and that’s not present in your work. In your poems you come across as a man who has lived life like everybody else, a man who has worked, had children, fought in the war, and whatever else that might have happened to him. Nor is it simply a poetry of witness, of looking at things from the outside. I mean, you’re part of what you see. I wonder if you’ve ever thought about this.

Mary: In the discussion that we were having yesterday, I think you were trying to find out why George gave up poetry, and how it could be that twenty-five years elapsed before he wrote again, and George kept saying to you, I don’t think we had lived enough, that we knew enough. And I think when we were very young, we both stopped writing because we were out there, away from school and away from home. It wasn’t just a flight. It was in the sense Heidegger uses — throwing oneself into what is out there. And I think George did that, and that when he felt he had done that sufficiently, he could then write about that experience — and that is a very mature and complete person who can recognize that he’s lived life, that it has meaning, and that he now knows what it is that he wants to say.

Auster: But at the same time, the poetry is not autobiographical at all. There’s very little of what you might call local color, very little narrative detail.

Mary: Well, the streets of New York, the hills of San Francisco, the sea, are a vast sort of background out of which he wrote.

George: I think I was again saying what is there. The men are there, and perhaps more noticeably there, but certainly there, certainly present. I keep saying this.

Auster: There’s a crucial section in “Of Being Numerous”: “It is difficult now to speak of poetry.” At the end you write, “This is the level of art / There are other levels / But there is no other level of art.” Somehow it seems to convey what we were talking about. Yet there are many other things. And if we’re going to do this, it has to be done in a certain way.

George: Yes, I think of it as a certain tightness. It’s not just going on and on, moving around. And always to remember, that many of the things that any poet is saying [have] the presence of music. And music is also that thing which goes outward and exists. Probably that.

Auster: I suppose, too, that people are taught that it’s good to express yourself, and art comes out of this bubbling up of personal expression. I imagine that’s what encourages people to do it in the first place. But with your work I don’t feel that at all. It seems to have come from another source, another place altogether.

George: Yeah. I’m feeling it as strange as you say it is. It’s always strange. It’s the fact of being there. Yes, I feel it is an opening-up, is what I mean. A consciousness again of the universe. A difficult word to use right here. I try to think now of my feeling and what I’ve written, and what comes to me again is the opening-up of things, the presence of things, and of course the inexplicable. It’s Cortés again.

Auster: So, in other words, the poetry can only be about what you don’t know. That’s what it means to you. To write only about things that are difficult or challenging.

George: Oh, it has to be a great deal smaller than the things that have happened. I can just about say that.

Auster: The poetry has to be a great deal smaller than the things that have happened. Yes.

George: It’s really that “Silent upon a peak” thing. And it is, of course, Reznikoff’s recitation over many different things.

Auster: But there again, talking about a poetry of anecdote — but Reznikoff is pure anecdote.

George: Pure anecdote, yes. But it would be very hard to express what comes of these little anecdotes. It always comes out — talking about spreading out there — and Rezi’s always coming out, small little man that he is.

Mary: One of the greatest of Reznikoff’s poems is that poem that you always remembered so often in the war.

George: Yeah, “the girder — ”

Mary: — “still itself among the rubble.” He is saying it’s a mysterious thing that we are here, but more incredible than this finger.

George: Yes, artistically, that’s what I’ve been saying.

Auster: It’s funny. I mean, I understand these things quite well. But it’s hard to try to get myself outside of it.

Geroge: I understand, it’s difficult.

Auster: I know, I know.

Mary: But if we knew perfectly what it is that you’re asking George to explain in his poetry, there wouldn’t be any need for the poetry.

Auster: Of course not.

Mary: Because different poetry is effective when you start it. If you haven’t, well then, you haven’t understood the poetry.

Auster: Absolutely.

George: And if I could say it without poetry —

Mary: You’ve said it so much in life.

Auster: And in the poems, surely it’s the same thing, again and again and again. That’s what it’s all about. I suppose from book to book it opens up. I mean, more is included in some way. And yet you can see it right from the beginning, I think.

George: There’s a story I read long, long ago about a young man, certainly not a boy, who was a painter, and didn’t feel his art had been good enough. He became very depressed, and locked himself into a room, and worked, painted, did nothing but paint for many, many years, with nobody in and nobody out. He spoke to nobody. At the very end of his life he had managed to complete the picture he had wanted to make, and it ended up — oh, he had many, many, many pictures, and he hung them on the wall, and he looked at this wall he was looking at, and he started to reproduce the wallpaper [laughter from the others] very, very well reproduced. We started with cars. That may be a very substantial element — wallpaper.

Mary: We’re trying to define something which is indefinable, trying to grasp something which you can’t hold in your hand. And yet we know quite well what we see.

Auster: I know, I know. Well, let me say something else, then. I don’t really want explanations, just thoughts about this, the poem in “Of Being Numerous”: “And one may honorably / Keep his distance / If he can.” Well, there are little contradictions that are interesting to talk about. One of the movements in the poetry is acceptance, participating in the given, going along with the world, recognizing that you’re just like everyone else, a human being living in a society. And yet there’s also a critical intelligence at work that says, “I have to step back, I have to look at what’s going on. A lot of this is very dangerous and harmful.” What precisely is this distance?

George: It’s the conflict in our lives — a very strong conflict between (we talked of this before) between politics at a time of crisis and poetry. It’s just saying that again, and opting for the moment for divorce, for his escape, or his right to escape, or the need that there should be some escape. But not really quite a version of what we thought at the time. There was a certain period there — we’re talking all the time about the real crisis, the fascists. It isn’t that I was particularly interested in politics.

Auster: Right. But even the act of politics, especially doing what you did, is a way of keeping your distance also. You see what’s happening and you think, “No, I will not accept it. I’m removing myself from this actuality. I’m going to change it somehow, make it better.” And in some curious way it starts from the same point, doesn’t it?

Mary: Well, you live a life and we determined very early that each of us is going to respect herself or himself the most. After that, we can build a life of respect and love with each other, that we could go out into the world, that we could live, that we could find out what the meaning was going to be, because we felt the life we had come from didn’t have meaning. That was decisive. If we had been satisfied with our families, we wouldn’t have done it, but we felt that meaning was lacking. There were wonderful people — my brothers, George’s father, his sister — wasted lives. Well, we wanted meaning. So we lived, and we tried to put as much meaning as we could into, I think, every different aspect of our lives which we now loved, in my category. In order, then, to do something about that and to express that, and to make it into some sort of a record of the meaning that our lives have had, requires art.

George: Again, one’s presence in the world. Which keeps coming back to these few things that depend on everything for us.

Mary: The miracle of being here. And here one wants to understand why. It’s a feeling of what this means, of what it has meant to me.

Auster: Well, here’s a question, then, perhaps the first real question. When you started writing again in ’58 so much had been welling up in you for such a long time. Was your impulse to look back and sum things up? Or was it simply to say, “I’m starting all over again, and here’s the poetry, and it’s looking forward into the future.” Or were you looking back and trying to make sense of what was the past?

George: Not that.

Auster: Not that.

George: The other way round. I think one learns from things. I think I’ve said before, if you write and rewrite and rewrite and rewrite, and it will not sound right, then you have to stop and say there’s something wrong with what I’m trying to say, why I don’t believe it. I can pitch it very close to what you’ve asked.

Auster: I wanted to ask, too, about methods of composition. I mean, how long do you work on a poem usually? How does it grow?

George: In the other room are stacks and stacks of notes. I write it and rewrite it, then get it again, and rewrite it again. I don’t think I have any other guide that I can think of right now.

Auster: You pursued one poem until it was finished, no matter how long it took. I see. Interesting. Clearly it’s a mysterious process. Have you usually had in your mind an idea of what the poem would be, each particular poem, a feeling, so to speak, for the body of it? It would be half a page long? It would have a certain tone, a certain gist?

Mary: What George has always said was, if you knew what the poem is going to be, sometimes you couldn’t get it written.

George: Yeah.

Mary: And that your great skill as a poet was that you could hang on to this, and keep it clear, and work and work and work and work until you knew that you had it. But it was, I suppose, how you would decide when you knew what this is, if you had. But that is how you decided. It wasn’t something written down, but it was an idea you had, something that you were going to express. But how you do that is a great mystery. But how you know when it’s accomplished is also a great mystery, except that, as George has said many times, the poem finally tells you what you think.

Auster: The theme you want to express is not articulated before you express it.

George: Very simple.

Auster: Has it happened, for example, that you would write a poem that was quite long, three pages or four pages, and then suddenly start striking out lines and sections, and collapse the whole thing into something shorter? Or was there a form in mind as well when you started?

George: I’m sure there was no form in mind. The other I’m not sure of. I don’t think so. I’m not even sure I said, “Now I’m going to write a poem.” [I] just started thinking or feeling, or feeling that I knew something.

Mary: George has a strange way of working which I learned from him, and was very useful, of covering a line that wasn’t right with the correction and of pasting on a different handwritten tape on top of it. And sometimes George’s piece that he was working on would get to be very thick, but underneath he would have all the other versions, or whatever the pages were.

George: I discovered it was absolutely necessary to my writing poetry. If I hadn’t thought of this idea of just pasting on, it would have gone on absolutely forever, the number of corrections I made.

Auster: In other words, you didn’t have to type out the whole poem again, and write it all out again. You just put in —

George: Yes, just pick out the wrong word, and put in a new one. It was absolutely essential. [I’m] a very, very slow writer, slower than anybody I’ve ever heard of. I can’t think of one.

Auster: The books were written fairly quickly, though.

Mary: Two years to each book.

Auster: Two years to each book. Very few people have written collections of poetry in two years.

George: I didn’t do much pasting.

Mary: You did an awful lot in all of those twenty-five years. It was ready, it was there.

Auster: No sooner had you finished one than another one was typed.

Mary: Immediately, yes. On the publishing, it was amazing to look back and see how it had happened.

George: I saved up themes while I was there — coming out of my politics.

Mary: There was everything — our lives, our relationship with each other, with Linda, with politics.

Auster: How were the books constructed? The order of the poems? Are they sequential? Chronological? Or did you rearrange the collections only after?

George: I doubt it. I don’t know.

Mary: You just put the poems together when you had them.

George: Oh, yes, but they were separate. It was already done, and I would think, rather, this would be a better position here.

Auster: Right, right. But I mean, I somehow sense in the book a sensitivity to the organization of the book, separate from the composition.

George: There was. That came later, I think.

Mary: But “Of Being Numerous” is certainly an organized series of — what is it — forty poems or sections?

George: I’m sure I can remember — I’m sure I do — putting the pieces together.

Auster: Speaking of the organization of books, it’s curious that in This in Which the first several sections of “Of Being Numerous” are there in another poem called “A Language of New York.” I guess you felt that the poem wasn’t finished, that there was more to be done.

George: Yeah. I guess I don’t know. Probably I did.

Auster: But then, in the Collected Poems, you have them both. You didn’t suppress the first one because it’s repeated in the second. You have them both.

Mary: And in the last book there are several repetitions. I think it went very well.

George: I think it was quite late when I first began. I think I was writing separate poems when I began, and I think it came to me that they would all go together, and that I could use the title of the poem that I valued very, very much, and which was later the opening of the poem, beginning with the word “The.”

Auster: But then, after you’d written the three books, more poems kept coming. Had you planned on that?

George: Not a plan. What’s that phrase? “Try and —” I forget what it was. I tried this word, I tried that word.

Mary: You wrote these three books, and then you continued to write more poems. I think you looked surprised that you continued to write. But there, there was still more poetry, and you wrote more poetry, until soon you had a collection, and it became a book.

George: I think I’m very interesting. [Laughter from the others.]

Auster: I’m curious to know what your response was to the response of other people when you started up again. It must have been encouraging.

Mary: I think that also is something miraculous. When George returned to writing, the people we met in New York, New Directions, were simply open and generous and ready for George. The most remarkable thing [was] when George’s first book, The Materials, came out, Harvey Shapiro called up and invited us to a party, and Eliot Weinberger invited all young people around who he thought might be interested in meeting him.

Auster: And as far as Reznikoff goes, what happened when you looked him up again? Was he glad to see you?

Mary: I think we told you he was not well. It was a very serious case. He had been desperately ill. I don’t know what was wrong with him. But he was also at the end of a lot of things. The law book company had closed, and he was at the end in some very curious way. And he and George began to see each other quite a lot, because you published books together, you set out on a reading tour together, and it was a very close association. And somehow I don’t seem to remember much about that. I remember meeting him in an automat. We always met him in an automat.

George: He always felt we were children. He would persist. He would have no other version. He thought it was very sweet of us to come.

Mary: And he agreed, he said yes, he was pleased if New Directions would — he was very amenable, and he was very sweet. He certainly looked very happy on the reading tour.

George: Oh, he was delighted.

Mary: You and Charles came out together to the West coast. You went to Oregon. Oh, it was quite an adventure. You went around.

Auster: A question I’ve often wondered about, something that puzzled me, was why [James] Laughlin didn’t publish other books by Reznikoff? What happened after that?

George: He didn’t want to print Reznikoff in the first place. And that book got published at my request. My sister paid half of the cost.

Mary: Yeah, but he wanted to do that, he wanted desperately to get in on that, to be a coeditor. Laughlin wrote to you and said that he would do this to please June [Oppen Degnan], but that he would have been honored to print your poetry.

George: Oh, he said that?

Auster: He’d print George’s poetry, but not Charles’s?

Mary: This was just concerning his relationship with June. He was doing it to please June, and that if June hadn’t wanted to do this in cooperation with the San Francisco Review, he would have —

George: He wrote me a letter, saying if I was embarrassed at being printed by my sister … I forget the words, and naturally I wasn’t embarrassed.

Auster: But I remember when I saw Reznikoff, he was still puzzled about Laughlin. He said, “Well, my books sold out. They did very well.”

Mary: They didn’t. And neither did Bronk’s books, and Laughlin remaindered them. He called up George. Remember?

George: Yeah, he got into a panic about money at that time.

Mary: He wanted to get out of publishing, to wind it up, and he called George and said, “Look, I can’t pay these storage fees any more, Bronk and Reznikoff.” And George said, “How much is it?” “Thirty-six dollars a year.” And George said, “Well, I’ll pay it. Send them here, and I’ll keep them for you.” And he said, “No, no, George, we have to run a business,” and so he remaindered them. He didn’t like Reznikoff, I guess.

George: He said that when he was a young man in college writing poetry he was very excited, but he’d lost his feeling for it. But he felt he had to carry the writers he’d begun with, and therefore he kept them. But he didn’t want any more writers was the point.

Mary: In a way he lost the whole impetus. I don’t think he cares anymore.

George: He did not like my poetry, and I don’t know whether it didn’t chime with him.

Mary: He wanted to place your book.

George: Did he?

Mary: Yes, he said that if June hadn’t wanted to do this, he would have demanded to do it.

Auster: That’s a curious thing. I had no idea that he didn’t like it.

Mary: I don’t know that that’s true. I don’t think it is true, because he was immensely proud of you.

George: Oh.

Auster: Well then, Bronk was one of the discoveries you made. Has there been anybody else since then who has impressed you and/or made a difference to you?

George: There certainly have been some things that I rather liked, or [would] recommend. Not very many certainly. I can’t remember intervening very much about anything else.

Auster: Not much in America, then? It’s curious, because you’ve always been so staunchly American, I mean, in your attitudes, early on, and really not, it seems to me, terribly influenced by what was going on in France [in the early 1930s].

Mary: Well, we said we’d look at pictures, and go round and meet Americans.

George: Yeah.

Mary: But even that wasn’t very important. It was fun going.

George: The first thing — was it? — In the American Grain.

Mary: Williams?

George: Williams, yes. I think probably that had something to do with it. I don’t think we said we weren’t interested in Europe, but we were very interested in Williams.

Auster: But there was no interest in, for example, looking up Joyce? You didn’t do that?

Mary: No. I knew his daughter, but we didn’t know Joyce.

Auster: You never met Beckett when you were in Paris? He’s just about your age. But you never heard of him or met him?

George: No. We didn’t try these things very much. Pound gave us recommendations to all the people he admired, and all of them were very, very nice to us, and all that. But it would be wrong to say we felt we were a different generation, if we felt we were of different age.

Mary: We were.

George: Oh, yeah.

Auster: But you weren’t looking for guidance from them in some way?

George: No, we were not at all. We enjoyed the conversations that Pound had set up for us. That was very interesting, but we went home.

Mary: We didn’t look up the circle of literary people, or names either. We didn’t try to duplicate the experience we had in New York with Zukofsky and his friends. We were not doing that. It didn’t make sense.

Auster: You didn’t go to Paris in the way other young people did — to live the artistic life.

Mary: We lived in the country.

Auster: And later on, when you were working in politics, did you ever think about the French Surrealists, for example? This is an example of a so-called avant-garde literary group with left-wing politics. They were trying to combine the two activities, and I wonder if that had any impact on you.

George: No, we thought it was wrong.

Mary: We pursued our own way, we were having fun, we went skiing, we enjoyed a students’ group, and, well, we just had fun.

George: We thought we were absolutely marvelous. That’s all it was about. [Laughter from the others.] We felt very patronizing. We were happier than anyone else.

Mary: We were having a very good time.

George: Yeah, we had a tremendous amount of fun. And these people held a very, very good picture of us. We would go home and congratulate ourselves on being exiles. We were slightly Objectivist. Yes, horses — we took them as real things. Horses we took as real things, and these other people were talking about publishers and —

Auster: But later on you didn’t think about the Surrealists and all their disputes with the Communists? It never was an issue?

George: No, it was nothing.

Mary: We were looking around to find the best place to do something about the situation. We attended a great many meetings and would come home and simply marvel at what people were doing. At one of the Communist meetings we went to, a woman was speaking about words of Communists in the air. It seemed some sort of a parachute dive. That was pretty serious. We read the literature. We haunted the movies and bookshops in France. Also the Social Democrat offices. We read their papers and magazines.

Auster: What I mean to say is, here was a left-wing group that wasn’t interested in Socialist Realism. And I’m not even saying that it’s particularly good. But [Louis] Aragon, for example — a poet like that. Did you ever read him or think about him?

Mary: We knew about him.

Auster: You knew about him.

Mary: We read about him, and read of his books. We went to Mexico, and Mexico was quite a tremendous experience, because it was a time of — 1934. The president had socialized many things. At any rate, it was quite a tremendous experience, and it certainly was socialism. It was very interesting. Children were the educated generation. Children about the age of ten had been through day school, and they were conducting the business of their nation. It interested us very much, and we felt that we then knew something about socialism on the ground where we had seen it. We made that shift when we went back to New York and joined the Party. I remember coming into Mexico City and looking at the art of the three Socialist artists. What was most convincing to me, I think, was that culture and politics could work together for the goal of socialism. But I certainly don’t remember very much of what we learned about Russia.

George: I feel a little strange about this. I know we were talking about what we did then in this extra light. I don’t know where you are.

Auster: I’m listening right now.

Mary: I’ll take a breather and take the puppy down.

[Intermission]

Auster: We’ll begin all over again. It’s been a very serious career, a very serious life, unlike other lives and other careers. You started out very, very young writing poetry. You were involved with some of the most interesting writers and poets of the time, and then, still at a very young age, you abruptly stopped writing. You did other kinds of things — among them political involvement, being a soldier in World War II, and then, rather late in life, at the age of fifty, you returned to poetry. And maybe what we could try to discuss is how, in spite of the evidence, it has actually been a continuous life, how everything is connected to everything else. And I think, perhaps, the important element in this is the attitude you had toward the writing when you were doing it at first — your aims, your motives as a young poet. I should mention the Romantics were the first poets that interested you. Then modern poetry was revealed to you all at once — Eliot and Pound, this was in Oregon, yes? — when you first started reading those people, both of you together for the first time. You went through a rapid early development, and soon you were writing important things and involved in a publishing venture.

Mary: We stopped.

Auster: Yes, you stopped, and yet what I mean to say is: at the moment you were doing it, the writing and the art and everything in the beginning, was it the most important thing in your life at that time? When you were young, becoming a poet — was that your great ambition in life?

George: Yes, definitely.

Auster: And the writing of poetry clearly gave you pleasure. Something you did every day, and it was the way you lived your life.

George: No, I don’t think that’s quite true. Not at all.

Mary: Well, when we were living in Le Beausset, I was painting, George was writing. That wasn’t any more important than the horse and getting to know the villagers and having George’s sister come to visit us. These were all equally important things. I think that any time, if anybody had asked us, George and I would have said, yes, we have a creative urge — something like that, which we’re going to perform in our lifetime. There was no time-schedule on it. I’ve never felt any time pressing on me. I don’t now, even at the age of seventy-two. There may not be many more years, but somehow I keep my mind on it, and I still feel impelled to go there and say, “What about it?” — something like that.

Auster: The writing and the painting were just part of your life. It was like breathing. It was something you did and cared about, but no more or less than anything else.

Mary: I think we would have said that was exactly the same thing — that the life had to be lived, and that out of our experience and the meaning that we found, we would then do something in the art. I think I always felt that.

George: And for me, at least, the sense of the world. That was really the thing. We were bound up in the little mores of the town. It was a sense of the world. We wanted to see it. You know, it keeps coming back to Reznikoff — the sense of the world, that these things are really there, that you have to go and see them more, to live with it, or not to live with it.

Mary: The world was real, and it was there. We wanted to see it and understand it.

George: That was our agreement and our passion.

Auster: But up till then you were dealing with your own experiences, your own background. You were saying, this is not really the real world —

George: Yes, we were.

Auster: — and we have to get outside of ourselves, to encounter what is there.

George: Yes, exactly.

Auster: But a man like Reznikoff, I think, said to himself, “Whatever I do is real. This is the real world because I’m in it. And here I am, and I’m writing about what I see. I’m not seeking it. I’m here, encountering it.” There’s a difference.

George: Yeah, yes.

Mary: I think we’ve always called it our education. We just dropped out of college because it didn’t have anything more to offer us. We’d had enough and we stepped forth. The trip to Europe was very thoroughly planned with Zukofsky. And we went mostly because the money that we had would be enough in France for us to live on and to publish the books. But certainly we intended to learn as much as we possibly could. I took it very seriously, and so did George. We put everything we had into it, to learn whatever we could learn. I think that’s why we sold the horse, because there was plenty of time for talking and for looking and digesting what we were seeing, and talking to people.

Auster: Hence the interest in seeking out other poets when you got to New York.

Mary: Well, the reason we left college, and the reason we had to, was that we recognized this agreement between us. George already considered himself a poet, and he had already been writing since he was a child. I had not been until I went to college. But it certainly was the central goal. Certainly the most important thing was to go and meet the people. We thought of going to Chicago and looking up the Chicago people. We didn’t do that. I guess it was somehow no place to begin, except that we were in Chicago.

Auster: When you went to New York, were you thinking of looking up specific people?

George: No, we weren’t part of the literary crowd, and we didn’t need to be.

Auster: You found these friends, and you shared certain ideas, and took off from there.

Mary: Zukofsky was already in correspondence with Williams. We were in a close association with Zukofsky. This was pretty much carrying out Zukofsky’s plan, and we said we will go and do it. That was the way we went to Europe, because we planned it this way. We were a proactive publishing venture. We read the proofs, found the printer, paid for it, and did all of those things.

George: We budgeted the meals per day.

Mary: But our own experience of it was our education.

George: Yeah.

Auster: I see. So the publishing venture was really Zukofsky’s idea, and you were the backers and the practical ones who did the work.

Mary: In a way we were the producers, and he was the director.

Auster: Right.

Mary: So it would never do to argue with him. We argued with him a bit about shipping bundles, and he wouldn’t carry a bundle.

Auster: And he was going to introduce you to Reznikoff?

Mary: Yes, and all his friends. We met all his friends.

Auster: Has there been a change in your thinking about writing since then?

George: No, I don’t think so.

Mary: Looking back after fifty years of activity, you have to just take what one deduces now as our motives then. We are looking back, aged seventy-two, and we can deduce now what motives we were possibly thinking about.

Auster: I suppose, though, when you did start again, there was an urgency about doing it that maybe hadn’t existed in the beginning.

Mary: As George said, no question.

George: Yes, it was very, very strange.

Mary: And that dream [while in Mexico] and going to the psychiatrist and so on, was rather a compelling way of telling yourself to get started.

George: Yeah, yeah.

Auster: But it’s almost as though that was the real beginning, then.

Mary: Yes, and then fortunately there was New Directions. And there was Reznikoff, there was Zukofsky — all of what George had left behind. He stepped back into it. He was well-received.

Auster: I guess what’s confusing about it right now, when I step back and look at it, is that many people write poetry in their youth — it’s a common thing — and then they go off to do other things. It’s very rare for someone to pick it up again later. Your early work was very successful in its way, and you were doing things that were important. And therefore it seems stranger to have stopped.

Mary: What did in fact interfere was Hitler, the Depression, and we can’t just say that we walked away from the poetry. It was a matter of history being more important. I think [Bertolt] Brecht shows that at certain times it’s treason.

Auster: Treason?

Mary: And it certainly is a matter of survival.

Auster: I’ll try again. Did you ever know or hear of Laura Riding?

Mary: Yes, I haven’t read her work. The feminist, yes.

Auster: A little bit, yes. She was actually from that same period, and she was someone who stopped writing altogether, gave up on poetry one hundred percent. Never wrote it again. She published a huge book of collected poems before she was forty, and then she stopped, but for reasons that were totally different, almost the opposite of what yours were. She was right-wing in her politics, but very active in the literary world of the thirties. The question is, in her terms, Objectivist. Therefore the poem is an object. Making something that works. It’s an artifact. It is an object as artifact. You’re creating something, therefore it’s an artifact. Whether an artifact can contain truth is something that she challenged, could no longer believe in. Then one has to say, what is truth anyway? And I think for her it was a kind of vague, Platonic notion of essence. That’s not something you’re talking about, is it? You mean the truth of experience, right?

George: Yes.

Auster: What is.

George: Yeah.

Auster: Well, to continue a little bit. When you got back from Europe, there was the break that you talked about last night. It’s quite fascinating, and what you kept saying was that it had to do with the two of you. I guess the depth of your connection made it possible. I don’t know if a solitary person could make a break of that sort at such an early point in his or her life. Do you know what I mean?

George: Oh definitely. Very definitely.

Mary: The only fear I had about George going to the war was that he might not come home. It was certainly right to participate in the war, and so on, because the war was a pretty dangerous venture. But I don’t think either of us ever doubted that at some time we were going to continue. Here we were with a child, and that was going to take a certain slice out of our life. But it was a compelling need for me.

Auster: You definitely wanted a child.

Mary: Oh, yeah, I did, yeah. That wasn’t to be begrudged. I think what we say now to young people is you have to live now, and you have live each part intensely, live it fully, and try to understand it.

George: You know what we felt, if you call your piece Meaning a Life. Yeah!

Mary: That’s the title of my book.

Auster: I think those things are stated very clearly in your book. A lot of the motivations become clear, especially after a second reading. During my first reading of the book, there were times when I was puzzled by some of the reticences. I was curious about those little gaps we talked about last night. I mean, what happened from ’37 to ’42, because there’s not a word about it in the book — or ’38 — after you got back to the States?

Mary: There were many gaps.

Auster: You remember where you were in ’38, ’39?

Mary: We were upstate.

Auster: You were still up there?

Mary: For two years, from ’38 to ’40. It was the very tail end of Spain and Czechoslovakia, Chamberlain. Those were the big events, we reckoned.

Auster: From ’33 to ’37 you were in New York City.

Mary: And we went upstate for two years, and we came back to Long Island.

Auster: In 1940.

Mary: Then in ’42, the war, the army, etc. Those weren’t very interesting years. The Party work was a disaster, a fiasco. I think I mentioned this yesterday. And George became a machinist.

Auster: You were disenchanted with the Party at that point. You did your jobs up there —

Mary: I don’t really remember very well. Oh, there was a big demonstration. It was very dramatic. A black [person] was accused of a murder of a cop — was that it? — and that was a very dramatic demonstration which George organized. There was a long, deep, furious protest of pharmacists, etc.

Auster: Well, here are some interesting questions, then: why did he become a machinist? Why did he pick that? How did that come about?

George: The proletariat. No question about it.

Auster: It was still part of the education we’ve been talking about? Consciously. You didn’t say, “It is my destiny to become a machinist in a factory.”

Mary: I think again, it was a test of manhood, to see what other men did.

George: Yeah, and to see if we could make a living.

Mary: We didn’t use the money that George had. George worked at times, and we never spent very much. We got on fine.

George: Well, the alternative — we wanted to be able to give ourselves —

Auster: But I mean, you never wanted a white-collar job, for example?

George: Not at all.

Auster: Did you feel at times like an actor — I mean, a pretender?

George: I remember [Joseph] Conrad deceived them. He didn’t tell them anything about poetry. But in the machine shop, no.

Mary: It was a similar group. There were people just like George going into the war effort, really. It was very good at that time. It wasn’t just [a] blue-collar working shift.

Auster: Because there’s a witty, amusing moment in the book when you get back to New York, and the taxi driver says, “It would freeze the balls off a turkey.” And you say, “Yes, it’s extremely cold.” You say that in the past George might have just responded in the same way.

Mary: But that was also, you see, when we got back from Mexico and we talked and talked and talked about what our attitudes were going to be, what the form of life was going to be. Linda was gone, she’d gone to school. We decided we will look up everyone, we will tell everyone anything they want to know. We will no longer be hiding anything about the Communists or the Communist experience.

George: The whole story is just that “we wanted to know — ”

Mary: “ — if we were any good out there.”

Auster: But I mean to say, that passage in the book seems to imply that for years you had made an effort to be someone other than who you were. Not as a poet, but simply as a man who wouldn’t say, “Yeah, it would freeze the balls off a turkey,” but someone who would say, “It’s extremely cold.” Forgetting about poetry for now, did you feel a strain in your personality because of having to deal with people in that way?

Mary: Yes, there was a strain. Of course there was. I used to ride to the relief bureau in the morning from Pineapple Street on the same bus as the woman administrator of the relief jobs, and she would give me this line of talk — trying to persuade me to stop bugging her was her motive, of course. And I never told her I was socially her superior, which I was.

George: Not to mention the same in the army. I was the wrong age, the wrong person. I wished to hell I wasn’t there. No question about it.

Mary: Well, they weren’t utilizing you in any way. You drove.

Auster: But there you weren’t pretending to be someone else. I mean, you were there.

Mary: To them [fellow exiles in Mexico] George was their Jimmy Higginson, Communist, and their handyman, and he would do the work, he and Carlos, whatever the problems were. And then William Carlos Williams had an autobiography published. A woman I liked best of any of the Hollywood people came and knocked at the door, and she said, “This says William Carlos Williams’s Autobiography.” She said: “You never told me!” And those people have never spoken to us again — that whole group. They felt that it was a deception pulled on them, and I don’t care. It was very tiring that their friendship was removed. But we certainly couldn’t do it differently at that time.

Auster: Suddenly it becomes such a very deep, spiritual drama. I had never thought of it in this way, before. I had seen your life as going from one thing to another, and at each moment you were confronted with a choice, and you made it, and then you did what you did. But it’s almost as though you went into the desert for a long time — in order to test yourselves.

Mary: That was true. Not quite as dramatic. Our life was normal.

Auster: All right, but there’s still something to be said about this. I haven’t done what you two have done, but I have spent a lot of time working menial jobs, especially when I was younger, which meant that I was with so-called blue-collar people every day, and it never occurred to me to not to mention who I was. Eleven years ago, for example, I shipped out on an oil tanker and worked as an ordinary seaman for six months. I had just gotten my MA in Comparative Literature from Columbia University. If someone asked me what I had been doing before I joined the ship, I would tell them that I had just gotten my MA, that I was writing, and so on. If that confused him, I figured it was his problem. I didn’t care.

Mary: But the people in the Communist Party, at the time we joined, could see that we were educated people, and they were desperately in need of people who looked and were exactly like us, especially in a marriage. The minute we told them who we were and what we were, we would have been required to work in their cultural area. If there was anything else we could lend ourselves to, they would have had nothing to do with us. So we had to deceive them.

Auster: Was there no way to do political work outside the Communist Party?

Mary: One could have been a Social Democrat, I suppose. One could have been something like ABA, or could have joined the Civil Liberties Union, or the ILB, which is a legal defense outfit. There are many ways for people who couldn’t become Communist. There was no reason, so far as George and I were concerned, why we couldn’t front openly as Communist.

Auster: When I think about the ship now, there was also the fact that I was Jewish, the only Jew on board. People ask questions, they always ask questions and I never hid the fact that I was a Jew.

Mary: You didn’t want to say something that was untrue.

Auster: No, I didn’t want to lie, I couldn’t lie. It caused some difficulties, of course. One fellow started taunting me, and after a while I’d had enough of it, and so I wheeled around — I don’t know where I found the courage to do this, just like a tough guy in a Western — took him by the shoulder, threw him against the wall, and said, “If you ever say that again, I’ll kill you.” And he said, “Oh, oh, OK. I won’t do it again.” And there was never any more trouble after that. But I certainly wouldn’t have killed him. If he had done it again, I don’t know what I would have done.

George: He played it for real. [All laugh.]

Auster: The odd thing about it for me that you two are probably the least duplicitous people I have ever met. You’re utterly straightforward. You say what you think, you do what you do, with no airs, no pretensions, and I can’t imagine that your personalities are any different now than when you were young.

Mary: We were bringing up a child. Linda was nine, and she was eighteen when she left, and the form of our life there was extremely upper-class, extremely bourgeois.

Auster: And then back to San Francisco. After so many years.

George: Yeah, yeah.

Mary: Let’s go for another walk. We’ll take the car down to the pier.

Transcript by Richard Swigg and Paul Auster. Copyright 2016 by Linda Oppen.