Vocabularies of Coolitude: South Africa

Francine Simon

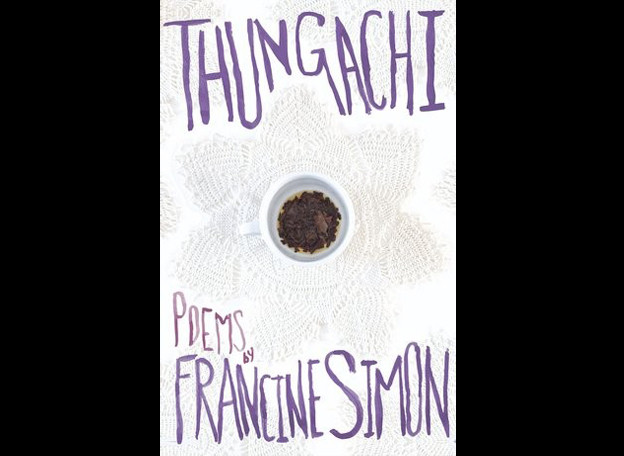

In her debut collection Thungachi (2017, Uhlanga Press), Francine Simon draws from the vast well of her Coolie inheritance to create poetry that speaks through the vocabularies of indenture. Being of Christian and Hindu Tamilian descent, Simon begins her book with the indenture story, fulfilling Vijay Mishra’s prescription that the Indian labor diaspora be haunted by its traumas of oceanic crossings.

Simon in the first poem writes,

When they came on the boats

one name was Sing(h).

The other, said and sung

-lost. (Simon 12)

She opens her collection with the arrival of her family in South Africa as laborers, lists caste names, and traces a patrilineal genealogy.

The collection continues with the poem “Dholl,” referring to daal, or the lintels, and begins with a list of provisions that indentured laborers were apportioned. She quotes directly from the Acting Protector of Immigrants’s “Notice to Coolies Intending to Emigrate to Natal, 17 August 1874.” She writes,

You will receive

rations as follows:

Dholl — 2 lbs per month,

Salt Fish — 2 lbs per month,

Ghee or oil — 1 lb per month,

Salt — 1 lb per month. (13)

The speaker is haunted by her history of indenture, where even these lists and directives can serve the poetics of her collection. The pun that unfolds in this poem is that the way the speaker says and the way that the “protector” writes daal sounds like the English word doll, which when spoken is a term of endearment.

Indeed, this kind of linguistic play is particular to Simon’s own Tamilian–South African community; she further develops this in her poem “Pp” where she strings together phrases and words from languages of indentured laborer communities. She draws on familial sources as well as Rajend Mesthrie’s work in Language and Indenture: A Socio-Linguistic History of Bhojpuri-Hindi in South Africa, and imbues the poems with personal experiences. She writes,

pakka ADJ

She’s not a pakka Indian. (22)

Through her inclusion of words, phrases, their variances and semiotic shifts, Francine Simon writes poems that continue the conversation started by Mahadai Das, David Dabydeen, Khal Torabully, and Sudesh Mishra by using what Mariam Pirbhai calls the vocabularies of indenture.

Coolitude: Poetics of the Indian Labor Diaspora