Coolitude poetics: Interview with Gaitura Bahadur

BIO

In her twenty years as a writer, Gaiutra Bahadur has been author, book critic, relief Baghdad bureau chief, consumer advice columnist, immigration beat reporter, Texas statehouse correspondent, children’s book writer, essayist, and independent scholar. Her narrative history of indenture, Coolie Woman, was shortlisted in 2014 for the Orwell Book Prize, the prestigious British literary award for artful political writing. She has won many residencies and fellowships for creative nonfiction, from the MacDowell Colony, Harvard’s W.E.B. Du Bois Institute and the Rockefeller Foundation’s Bellagio Center in Italy, among others.

At 32, she was named a Nieman Fellow at Harvard for her decade of work as a daily newspaper reporter, primarily at The Philadelphia Inquirer. Gaiutra has reviewed, reported or written for The New York Times Book Review, The Nation, Lapham’s Quarterly, The Virginia Quarterly Review, Dissent, Foreign Policy, The Guardian,and The Washington Post, among other publications. She has served as a judge or nominator for several literary prizes, including the PEN/Jean Stein Award for Literary Oral History. Gaiutra’s debut fiction, the short story “The Stained Veil,” was first published by the Commonwealth Writers Foundation in London and is forthcoming in the anthologies Go Home! (New York: The Feminist Press at CUNY, 2018) and The Red Hen Anthology of Contemporary Indian Writing (Pasadena, California: Red Hen Press, 2019).

Gaiutra was six when her family emigrated from Guyana to Jersey City, New Jersey. She holds a BA in English Literature, with distinction, from Yale University and an MS in Journalism from Columbia University. She is currently a visiting scholar at NYU’s Asian/Pacific American Institute.

BOOK BLURB

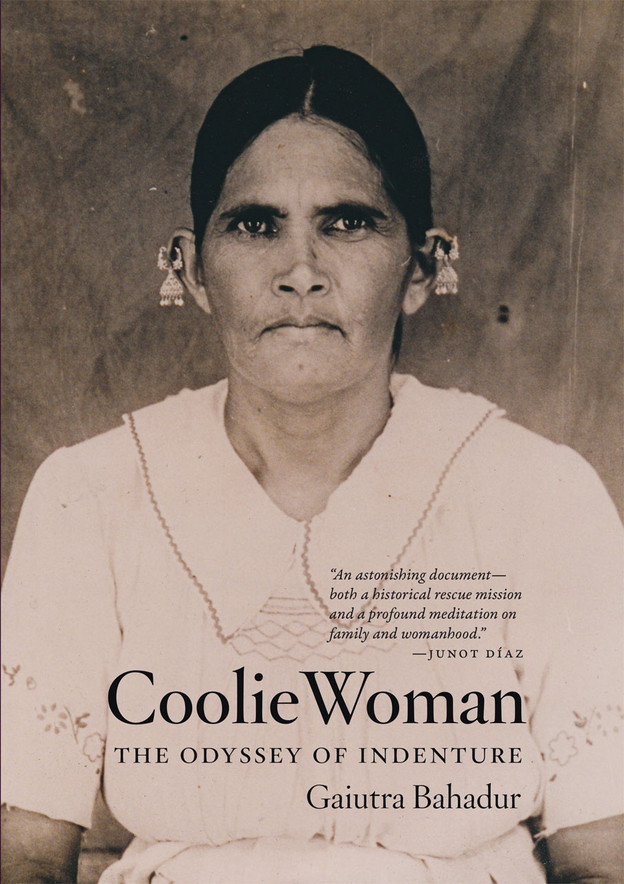

Coolie Woman interweaves the author’s journey to uncover the mystery behind her great-grandmother’s exit from India, pregnant and alone in 1903, with the larger epic journey of Indian indentured women to the Caribbean as sugar plantation laborers from 1838–1917. The book is cross-genre, as much immigrant memoir and immersion journalism as it is narrative history or collective biography.

Published in the US by the University of Chicago Press in 2013, with international editions in Great Britain, India, and South Africa, the book won the Gordon K. and Sybil Lewis Prize, awarded by scholars of the Caribbean to the best book on the region, and was shortlisted for the Orwell Prize as well as the Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature, in the literary nonfiction category.

Readers and critics have embraced the book as an excavation of the lives of hidden subaltern women — in the words of Junot Díaz, “both a historical rescue mission and a profound meditation on family and womanhood.” The Library Journal recommended it in a starred review as “a spellbinding account of a story that needed to be told,” and The Women’s Review of Books as “a moving, foundational book.” In England, The Guardian called it “a genealogical page-turner interwoven with a compelling, radical history of empire.” South Africa’s Sunday Times read it as “an ode” achieved through “exceptional detective work.” And the blog Mumbai Boss named it the best nonfiction book published in 2013 in India, where The Business Standard’s critic concluded that it “will permanently change our view of the past.”

Rajiv Mohabir: Congratulations for your wonderful accomplishment of bravery and stamina. Coolie Woman: The Odyssey of Indenture is a book that will be invaluable to the study of the Caribbean as well as the coolie labor trade. What brought you to begin writing this work that straddles creative nonfiction and journalistic modes?

Gaiutra Bahadur: Thanks, Rajiv. This project began with a riveting ancestor. I had been intrigued by my great-grandmother Sujaria from the moment my father shared the bare bones of her story with me. I remember his words exactly: “She was a pregnant woman traveling alone.” He told me that in 1997, the year I graduated from journalism school. It took another decade for me to begin pursuing her story in earnest, a decade that I spent telling other people’s stories as a newspaper reporter. That experience was very good training for turning the investigation inward, to my own history, when fortune finally allowed me to delve into the circumstances of her leaving India.

It seemed like bad fortune at the time. (In retrospect, I see that it was a gift.) A quarter of my newspaper’s editorial staff were laid off during bad times for the industry, and as one of the less senior reporters at The Philadelphia Inquirer, I was suddenly without a job. I had an amazing soft landing, with a fellowship at the Nieman Foundation at Harvard in 2007–2008. During winter break of that year, I traveled from Cambridge, Massachussetts to my great-grandmother’s village in Bihar to see what I might find out about her. I found relatives who claimed her — and me. And I also traveled to London, where I spent several weeks reading Colonial Office correspondence from the year my great-grandmother left, hoping for some stray mention of her. I didn’t find any references to her — that was mad, improbable, wishful thinking if ever — but I did find a storyline bigger than either her or me.

The letters revealed that there was a shortage of women on the plantations in Guyana and the very summer she left, British officials were wringing their hands over ships stranded in the Hooghly River because there weren’t enough women aboard. (To sail, a ship needed to meet a quota of 40 women for every 100 men aboard.) I began to see the outlines of a larger canvas taking shape, a canvas in which she was just one of thousands of equally haunting figures. What would it mean for a woman by herself, bearing a child, with no husband by her side to enter a context where she was scarce like a commodity? And did that context perhaps explain why she ended up on an iron sailing ship called The Clyde headed for the other side of the world in the middle of the monsoons?

At first, I was intrigued by my ancestor because I thought she had to be exceptional. What woman alone, in her condition, undertakes a taboo, arduous, identity-erasing journey like that? But what the archives revealed was that she wasn’t exceptional. She was representative. The year she left, three-quarters of the women who sailed from India as indentured servants didn’t have a husband by their sides when they left. Eventually, I was able to calculate that roughly 10 percent of women on her ship fit her profile exactly: pregnant, husbandless. The moment I could see her in this bigger picture, could see that her tale would be the tale of so many others, I knew I had a book to write. I could see her shadow in the archive, gathered with so many other shadows, all of them moving, and I wanted to chase after them. Their very elusiveness was my motivation. Who were these women huddled in the hull’s curve? I had to try discover their individual stories and tell them.

Rajiv Mohabir: Your book has made a very important intervention as it considers subaltern history and voice. You begin the book in an exploration of your great grandmother Sujaria who, according to family lore, was Brahmin. Can you tell me a little about your experience of working with the vast archives that you waded through for this project? How difficult was it to find the information that you needed for this book project?

Gaiutra Bahadur: Actually, it was the archive that told me she was Brahmin. The Brits were excellent record-keepers. Every indentured servant who left India was handed an emigration pass. It provided lots of detailed information: caste, village of origin, father’s name. I found my great-grandmother’s pass in the archives in Guyana. It was crumbling, in a yellowed sheaf with the passes of almost all the other indentured men and women on her ship.

It’s a spooky document, bureaucratic yet intimate. It told me, for instance, that she was pregnant four months when she left Calcutta. It told me, too, that she had a burn mark on her left leg. Here was that shadow again, except now she had a scar on her leg that made me wonder. Later I analyzed the information on the passes of everyone aboard, so I could provide a portrait in both numbers and words of who was aboard that ship: a hermaphrodite, a woman with her left nostril cut, twenty-eight single mothers, twenty-two pregnant women, 147 women traveling without husbands.

I was working like an investigative reporter in the archives, but also as a descendant, someone personally connected to the documents. I worked with the ship manifest the same way I worked with all the other archival evidence, trying to hit two registers: analytical and affective, rigorous and lyric. I had to aim for both, to make up for the fact that the indentured women are not present in the archive speaking for themselves, in their own voices. They did not leave behind letters, diaries, biographies. They did pass down stories sometimes and folk songs that spoke to the wide spectrum of their experience: their joys and their pain. I know you know, Rajiv! Your recordings of your grandmother’s folk songs are haunting.

My point is that I had a rich paper trail to work with, in archives and libraries London and Georgetown, Guyana’s capital. There were ship manifests, reports by immigration agents, diaries by ship surgeons and captains on nearly one hundred voyages to the Caribbean, newspaper articles about indentured women killed on the plantations, transcripts of inquiries into uprisings on the plantations, reports on white overseers who slept with Indian indentured women. I spent three years reading and analyzing hundreds of cases. But in the end, no matter the respect I had for all that archival evidence, I had to pay even greater respect to what wasn’t in the records: to the gaps and the silences that continued to shadow these lives.

In one exceptional case, I was able to listen to the voices of Indian women who had once been indentured. In the 1980s, sociologist Pat Mohammed interviewed the last generation of “coolie” women in Trinidad. The audio recordings are kept at the University of the West Indies, as are transcripts of similar interviews done by linguist Peggy Mohan (now a novelist of indenture). I am so grateful for their work and for oral histories with that generation that were conducted in Fiji. I tried to serve as a dummy in the lap, with them — the ancestors and elder scholars of indenture — working my mouth, putting words into my mouth as ventriloquists would.

Rajiv Mohabir: You trace your use of the word to the poet Rajkumari Singh’s “I am a Coolie” as well as to David Dabydeen’s in “Coolie Odyssey.” This feel like an invocation to the ancestors. You mention Coolitude as a concept and I was wondering if you can talk about your relationship to this kind of articulating a Coolie diaspora as it relates to the Guyanese context.

Gaiutra Bahadur: Well, the word “coolie” is charged, and I anticipated the problems some would have with my use of it. That’s what led to the preface, “The C-Word,” which provides an etymology of the word in the context of indenture and a creative genealogy, alluding to an earlier generation of writers who have reclaimed the word for literature, including Rajkumari Singh, David Dabydeen and Khal Torabully. If coolitude means pride rather than shame in shared origins in indentured labor, across many seas and many nations, from Trinidad and Guyana to Fiji and Mauritius, I am glad to articulate that pride as those artistic forebearers have. I have nothing but awe for the hard work, endurance, and feats of survival and reinvention for our indentured ancestors.

To be honest though, Rajiv, I knew I would call the book Coolie Woman years before I became familiar with Coolitude as a concept or an aesthetic movement. I chose the title because it was accurate literally and metaphorically. My book is about an indentured woman, and “coolie” was the British bureaucratic term for indentured laborers; and my book is about the burdens that Indian indentured women hefted in history. “Coolies,” in the original use of the word in the subcontinent, carried loads on their backs as manual laborers at docks and railways. I wanted a title that would authentically capture in all its rawness the weight indentured women shouldered, as victims of violence, as paragons of a family’s honor, as the ones who had to meet the productive and reproductive needs of men of all races on the plantations. I wasn’t trying to be polemical or to position myself in a literary tradition. I was just trying to be truthful about the past.

As I became more familiar with the literature on indenture, as the stories in the archives spoke to and haunted me, as my years with this material grew long, I did come around personally to a tenet that I believe is at the heart of coolitude. It has to do with origin stories and where we imagine our roots to be. For me, it’s not in India. It’s on the seas that led away from India. This isn’t to deny the cultural influences from the villages of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh that persisted across and sustained generations.

But I didn’t come to an understanding of who I am through any imaginary homeland, be it India or Guyana. I arrived at what felt like a genuine identity by grappling with the system of indenture. That institution, coming in the aftermath of slavery and in some ways like a new form of slavery, changed us in profound ways. We’re heirs of a form of bondage like descendants of the African enslaved. This is a parallel sensibility that I think David Dabydeen works from in his terrific historical novel The Counting House, where an indentured woman takes the place of an African woman in a plantation manager’s house and in his lusting, exploitative eye.

In imagining our birth as a “coolie” people on the seas, I am hardly alone. It’s a cue I took from the writers on indenture I was reading, like the Canadian-Guyanese poet Arnold Itwaru, who spoke of the indentured on those vessels from India as being “middle-passaged” amid “a scatter of worlds and broken wishes / in Shiva’s unending dance.” As I was looking at one ship report after another that recorded Indian lives aboard with two tallies, one for deaths, one for births, I couldn’t help but connect this to “Shiva’s unending dance.” I couldn’t help but invoke the Hindu god who destroys in order to create, who dances in a ring of flames to maintain the universe’s ceaseless cycle of creation and destruction. And swirling in between the poet’s metaphor and the mortality and birth rates I was calculating from ship records, I kept hearing the words of a woman interviewed in 1978 by Peggy Mohan, while she was doing her doctoral work in linguistics in Trinidad. The woman, born on a ship from India to the West Indies in 1888, told the story of her own beginning: “On that mad ocean, when all was tossing, people’s heads were spinning, and then labor pains started for [Ma] to have her child, on that mad ocean I was born, on that mad ocean I came to life.

Again serving as the dummy on the lap, I synthesized all the stories I had heard and read about the crossing the “Pagal Samundar” or mad seas around the Cape of Good Hope, on the journey from India to the Caribbean. I used them to write a sort of creation myth, which comes as close to a statement of how I conceive of Coolitude as possible. I think it might also be how Khal Torabully, who conceived the term, imagines it — as a new beginning, a rupture, a decisive break with India. If you’ll indulge me, I’d like to quote to show how I used the story of the woman born on that mad ocean:

“She was describing her own origins but, with her incantatory words, she could have been telling the creation story of our people, mine and hers. She could have continued, in her voice of myth: In our beginning, there was a boat. On that mad ocean, we came to life. We passed the red sea to reach the black. The water was blue before it was green, and then it was mud. We crossed seven seas: seven shades of water, shades of darkness and light, light that died and darkness that was born, darkness somehow extinguished and light rekindled. The captain’s wheel became Shiva’s fiery circle, turning and turning in its cosmic spiral. And in the gyrating of the gales, and the churning of the waves, as one steered and the other danced, we became new. The moorings of caste had loosened, and people who had left behind uncles, sisters, husbands and mothers substituted shipmates, their jahajis, for kin. Unraveled, they began, ever so slowly, to spin the threads of a novel identity.”

Rajiv Mohabir: The rhetorical device of using interrogatives instead of declaratives gives the reader a simultaneous sense of discovery with the author. I was wondering if you might speak about your theories of form as I also know that you write fiction as well. What are the differences between writing a creative nonfiction and fiction?

Gaiutra Bahadur: It was a short story that inspired that rhetorical device. I’m a fan of the New Yorker Fiction Podcast. The podcast the month I sat down to start writing Coolie Woman was Donald Barthelme’s short story “Concerning the Bodyguard,” read by Salman Rushdie. The stylistic fireworks here, the explosive and impressive play with form, is that the story is written almost entirely in questions. It’s about a bodyguard to an unnamed public figure, an assassination target in an unnamed country, a repressive one. It makes sense that every object in that bodyguard’s field of vision would provoke questions.

I experimented with the same device in writing about the journeys of indentured women because their world too was shot through with tension and uncertainty. These were actual women who lived in a historical, nonfictional world, and the details of their voyages and landings were only too real. I come from a newspaper background, so I’m very rigorous about fact and detail and sourcing. If I speculate in Coolie Woman, or project my own questioning voice, the reader knows it. I show the seams — the places where the techniques of a short story meet the material from the archives. And I also show the footnotes. It’s important to me that the reader understands that even when literary devices are being used, I don’t invent incident or the details of setting. I don’t reconstruct dialogue or write it as I imagine it might have happened, as some memoirists do. If I don’t have a source for a detail, a transcript of a court hearing, a ship surgeon’s diary, a travelogue etc., then I don’t write it. The reader’s trust in me is what’s at stake.

All of that said, written sources are not godly, and I think one of the things creative nonfiction can do is to question them, to move the tectonic plates under them, when it’s right. There’s a troublemaker strand of historiography that holds that the archive is a fiction. The testimonies of a wide range of subaltern people are absent from the written record that informs history, unsettling its claims to objective truth. In his essay “The Muse of History,” Derek Walcott examined a related anxiety about the integrity of sources for history. He rued the creative predicament of postcolonial New World poets to whom recorded “history is fiction, subject to a fitful muse: memory […] everything depends on whether we write this fiction through the memory of the hero or the victim.”

There are definite problems of bias and elision in archives that favor the lettered and the privileged. What that does is destabilize history as a genre. It opens it up to ambiguity and contradiction, suspense and subjectivity, qualities more the terrain of the novel. If history can be fictionalized in this way, can fiction serve as history? I think so. There’s an opportunity for the imagination to go where the sources cannot go, to the interiority missing from the archives. Fiction can fill in the gaps created because indentured women (for one example) did not leave behind diaries, letters, autobiographies telling us what they thought and how they felt.

I get the profound instability of genre — how history can be fiction and fiction, history — but I am relatively old school. I do think there’s a clear difference between the two genres, and it comes down to a fidelity to the facts as I can know them. The inventiveness in creative nonfiction is a matter of style, of form — not of content. As for fiction that draws from real life or historical material, there are some experiences perhaps too traumatic to confront directly. In those cases, the indirection of fiction might be the only way to record what happened. There’s an alchemy that can take place in shifting genres, and facts can be transformed into a higher psychological truth through fiction. I’ve written only one short story, and it wrote itself, as if I were possessed, truly.

Rajiv Mohabir: Can you tell us about any other projects that you are currently working on?

Gaiutra Bahadur: My current book project defies easy classification. It seeks to tell the story of Janet Jagan, the Chicago-born granddaughter of Jewish immigrants who in her seventies served as president of Guyana, formerly Britain’s only colonial foothold in South America. It was a country she had adopted as a young woman, after falling in love with its future independence leader. (He was in Chicago studying to be a dentist during World War II.) And it was a country whose independence she too had fought for, wading into rice paddy fields to talk to the wives of peasant farmers about the need to break from Britain and cofounding a political party. In 1999, when she was elected to succeed her husband as Guyana’s president after his death, Jagan became the first American woman to serve as a head of state anywhere in the world.

My book, however, won’t be a straight biography of Janet Jagan. Instead, it aims to be a book-length lyric essay that explores the nature and ironies of American exceptionalism and the American Dream (what Obama described in his farewell address as “the beating heart of our American idea”). I’ll accomplish this by conducting in unison the stories and voices of a chorus of Americans who moved into and out of my tiny birthplace, a tropical satellite state that was “nothing but a mudbank” by one diplomat’s account, but whose Marxist leader made John F. Kennedy so afraid during the Cold War that the US covertly intervened to maneuver him from power. The leader was Janet’s husband, who was also her close political partner. The way their ouster was achieved, through racially charged violence that left a long and bitter legacy, provides a textbook case of American exceptionalism gone awry. The other American figures whose trajectories through Guyana will move the theme forward include (1) CIA agents and U.S. labor union officials on the ground there stoking racial rivalries in the 1950s and 1960s, (2) Black Power fugitives, writers, teachers and artists seeking haven from a racist America in the 1970s, when Guyana had become a stop on the Pan-Africanist underground and (3) emigrants like my own family who fled in the opposite direction, fully wanting to believe in the American Dream.

The research for the book spans a multiplicity of diverse subjects and concerns: the figure of the American woman abroad, the Jewish Left in the US, anticommunism, the Cold War, anticolonialism, the American Black Power Movement, Pan-Africanism, COINTELPRO, the contours of post-1965 US immigration and America’s history with xenophobic, racial, and police violence. As I conceive it now, I will draw the strands together through a narrative that gains its momentum as much from recurring images and ideas as much from incident. Going back to your question about genre, I guess this is what makes my work fundamentally creative nonfiction. I’m invested in a maddening amount of research, both wide and deep, but I always want to write it in the most creatively challenging way! Otherwise, I get bored.

Coolitude: Poetics of the Indian Labor Diaspora