Queer Coolitude hauntings in motion

Shivanee Ramlochan speaks of ghosts

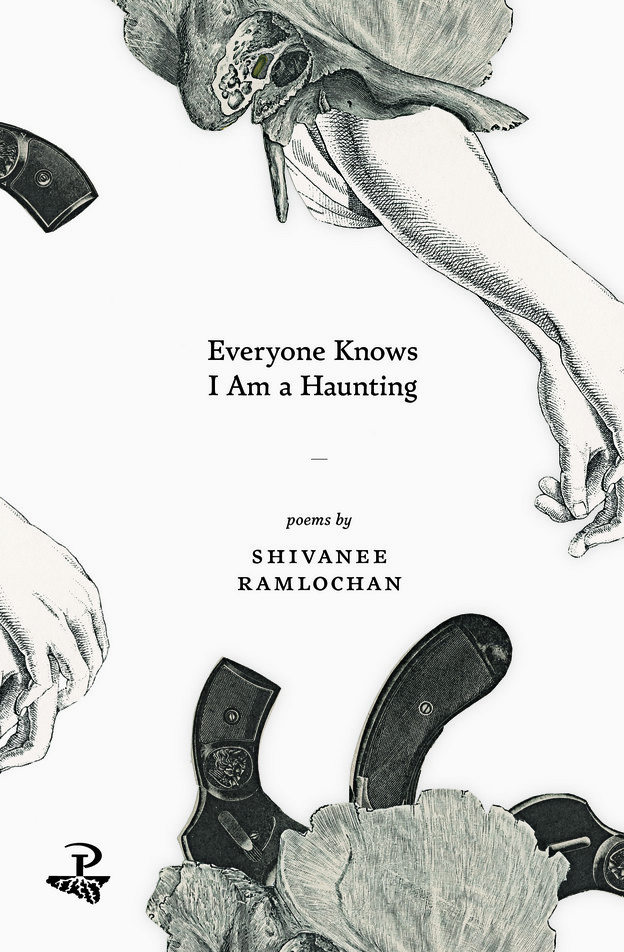

Shivanee Ramlochan, author of Everyone Knows I Am a Haunting (Peepal Tree Press, 2017) writes a Coolitude poetics and achieves a dazzling sense of historical hauntings in her debut collection of poetry. The ghosts leap. Her collection quite literally includes duennes and jumbies as a way to write about the missing, the dispossession, and the longing for a wholeness that haunts her speakers.

The Hindu pantheon as well as Christian deities make their ire known in her lines through multiple patriarchal failures enacted upon women. And in these poems the speaker is haunted by sexual violences and the colonial imposition of gender identities, which Shivanee Ramlochan works into a process of transcreation from the fragmented archive she inherits. The poet’s hauntings hang at the intersections of patriarchy, queerness, violence against women, colonial narratives, and a reclamation of voice. The ghosts: indenture, language attrition, loss of religious identities, and homophobia.

In the poem “A Nursery of Gods for My Half-White Child” the speaker considers their Hindu inheritances and layers patriarchal oppressions into the expression of the gods. Indeed, this poem is a list of cultural losses the speaker aims to reclaim with a political orientation of empowering the oppressed. From the goddess Kali, the lesson for the “Half White-Child,” a metaphor for the colonized subjectivity, the speaker admonishes the self,

— If you must fry for a man, do it dancing on his skull (11).

The poem rushes to a closure that is both the birth and death of the speaker’s own self as understood as separate but contiguous. The figure of the daughter is also the mirror of the self. Ramlochan writes,

drown me to sleep with the gods you have made

shrieking, floating, bastarding into birth (11)

The amniotic is also the killing water. The self births and ends the self. There is no “child” as such that bears a future — that is, the child is not the affective repository of what’s to come. Rather it is the speaker who creates herself with remembering, listing, and transforming the forgotten and neglected gods.

For the poet, hauntings from a history of indenture undergird the usages of not only postcolonial gender identity but also that of language. In “The Virgin Speaks of What She Endured,” along with the patriarchal constraints on women, or those perceived as women, there is a linguistic haunting that plagues the speaker wherein the realization of self comes through the renaming of self in reclaimed language.

Ramlochan’s speaker first regurgitates a swallowed language before naming themself in their own language. She writes,

By the fifth week the bruised bark had nothing left, so we began to eat

language

… The statues of the men who spoonfed us English

are ground to glassine …

… I am no longer your bride …

… Starving, I unswallowed the words that mattered (26)

In these excerpts strung together what emerges is the idea of reclamation — a reincarnation, reusing, recorporializing of the ghost. The concluding lines of the poem switch into a direct address to the reader, implicating the reading of the speaker’s self as changeable,

Come, burst me into song.

This move brings the speaker into the reader’s present, another kind of incarnation. What lives again is transformed in and by the mystery of reincarnation. The poet, inspired by Hinduism, shows the potential for transformation.

The transformations do not only end in language, but also in self-perception. In much of this collection the shifting familial ties, queer kinships, and refusal of silences regarding sexual abuse allow for a complicated ghost-scape. In the poem “All the Dead, All the Living” the speaker transforms into the lagahoo, the Trinidadian shapeshifter, kin to the werewolf,

turning wolf

to woman

to wolf again. (50)

Here, the hauntings are more than spectral, but the very much alive attitude that dehumanizes the queer brown woman into the base, the animal. For the speaker, there is joy in this ability to walk different spheres — the haunting of dehumanization in colonial histories she pairs with Jouvay celebrations. There is a velocity to the speaker’s voice.

The final poems in the collection show a noteworthy shift, extending this notion of queerness as visible and celebratory. The last poem addresses a queer man who brings “faggots to [his] bed” (70). She writes,

Your father said not to take faggots to your bed, so you called them festivals (70)

Addressing directly the need for queerness in celebrations, orthodox and in public spheres, the word “festival” becomes a hinge. It causes the reader to return to the very beginning of the book and to look again at all the Hindu images of Divali, Holi, and other holidays and read the queerness into the “festivals.” The voice continues to trace the queer images throughout the festivals of Phagwa, Samhain, and Hanukkah. In this retrospectatorship, the book at its last possible moment explodes with new possibilities for the reader, another type of reincarnation, another type of haunting, another moment of queerness on the horizon.

Coolitude: Poetics of the Indian Labor Diaspora