Twenty-six items from Special Collections (g)

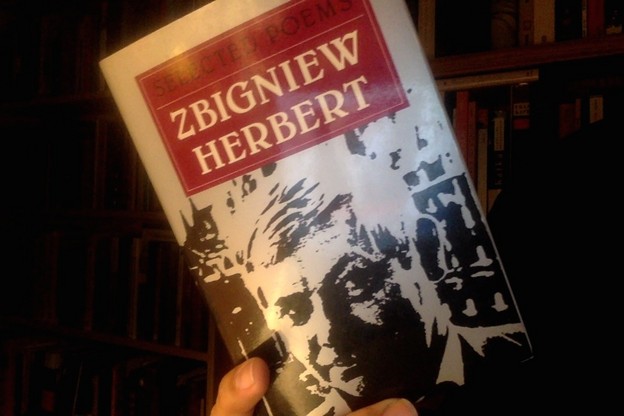

Exhibit 'G': Polish. (Zbigniew Herbert, five prose poems, 1950s and 60s)

Bibliography: Zbigniew Herbert: Selected Poems, translated by Czesław Miłosz and Peter Dale Scott (originally published as part of Penguin Modern European Poets, 1968; reprinted by Ecco Press, 1986).

Back story: I’ve not found it easy to get good information on Zbigniew Herbert’s prose poetry. Here’s all I know. There are twenty-five prose poems in the book pictured above. They come in four very unequal clusters, spread at intervals throughout the collection. I guess they are either mainly or entirely derived from material that appeared in Herbert’s second, third, and fourth books (Hermes, pies i gwiazda [Hermes, Dog and Star], 1957; Studium przedmiotu [Study of the Object], 1961; and Napis [Inscription], 1969). This guess is based on the fact that part of the translator’s note in Elegy for the Departure and Other Poems (Ecco, 1999), which only includes pieces that had never before appeared in English, reads: “Part III comprises prose poems. They span the period from 1957 to 1969, and their order is chronological.” Also I observe there are no prose poems in Report from the Besieged City (Ecco, 1985), and I doubt there were any in Mr Cogito (1974). But I don’t know.

I’ve been thinking about prose poetry lately, partly because I’m convinced half of all magazine verse today is prose poetry with line breaks. There is no need for that. Would line breaks add anything to the pieces below? Has anyone ever been tempted to install line breaks in Baudelaire’s Petits Poèmes en prose—?

Meanwhile, the “surprise quotient” is kept to a high standard in the following pieces. It’s one thing to say something surprising; it is quite another to keep it coming, sentence after sentence. My figure for this is a boxer working what’s called a “speed bag.” It’s that leather, teardrop thing about the size of a melon, hangs at eye level. You do this rolling punches thing and it sounds like a machine gun.

Hen

The hen is the best example of what living constantly with humans leads to. She has completely lost the lightness and grace of a bird. Her tail sticks up over her protruding rump like a too large hat in bad taste. Her rare moments of ecstasy, when she stands on one leg and glues up her round eyes with filmy eyelids, are stunningly disgusting. And in addition, that parody of song, throat-slashed supplications over a thing unutterably comic: a round, white, maculated egg.

The hen brings to mind certain poets.

A Russian Tale

The tsar our little father had grown old, very old. Now he could not even strangle a dove with his own hands. Sitting on his throne he was golden and frigid. Only his beard grew, down to the floor and farther.

Then someone else ruled, it was not known who. Curious folk peeped into the palace through the windows but Krivonosov screened the windows with gibbets. Thus only the hanged saw anything.

In the end the tsar our little father died for good. The bells rang and rang, yet they did not bring his body out. Our tsar had grown into the throne. The legs of the throne had become all mixed up with the legs of the tsar. His arm and the armrest were one. It was impossible to tear him loose. And to bury the tsar along with the golden throne—what a shame.

From Mythology

First there was a god of night and tempest, a black idol without eyes, before whom they leaped, naked and smeared with blood. Later on, in the times of the republic, there were many gods with wives, children, creaking beds, and harmlessly exploding thunderbolts. At the end only superstitious neurotics carried in their pockets little statues of salt, representing the god of irony. There was no greater god at that time.

Then came the barbarians. They too valued highly the little god of irony. They would crush it under their heels and add it to their dishes.

A Devil

He is an utter failure as a devil. Even his tail. Not long and fleshy with a black brush of hair at the end, but short, fluffy and sticking out comically like a rabbit's. His skin is pink, only under his left shoulder-blade a mark the size of a gold ducat. But his horns are the worst. They don't grow outward like other devils' but inward, into the brain. That's why he suffers so often from headaches.

He is sad. He sleeps for days on end. Neither good nor evil attract him. When he walks down the street, you see distinctly the motion of his rosy wings of lungs.

The Hygiene of the Soul

We live in the narrow bed of our flesh. Only the inexperienced twist in it without interruption. Rotating around one's own axis is not allowed because then sharp threads wind themselves on to the heart as on to a spool.

It is necessary to fold one's hands behind the neck, half-shut the eyes and float down that lazy river, from the Fount of the Hair as far as the first Cataract of the Great Toenail.

•

Correction [2/3/16]: The paragraph below is from Bogdana Carpenter’s “The Prose Poetry of Zbigniew Herbert: Forging a New Genre,” which appeared in The Slavic and East European Journal, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Spring 1984), pages 76–7:

____________________

Herbert’s first volume of poems Struna światła (Chord of Light, 1956) contained no prose poems, but his second volume, Hermes, pies i gwiazda (Hermes, Dog and Star, 1957), published almost simultaneously with the first, contained a large number—sixty out of ninety-five poems are prose poems. From this point on, prose poems are present in all of Herbert's collections of poetry. In Studium przedmiotu (Study of the Object, 1961) the ratio of prose to verse poems is eighteen to twenty-eight, in Napis (Inscription, 1969) it is fourteen to twenty-six, and in Pan Cogito (Mr. Cogito, 1974) it is five to thirty-five. Although their number varies in individual volumes and significantly decreases in Pan Cogito, they are a constant feature of Herbert’s poetry.

____________________

Twenty-six items from Special Collections