Twenty-six items from Special Collections (d)

Exhibit 'D': Mahārāṣṭri Prākṛt. (Specimens from the Gāthāsaptaśatī of Sātavāhana Hāla)

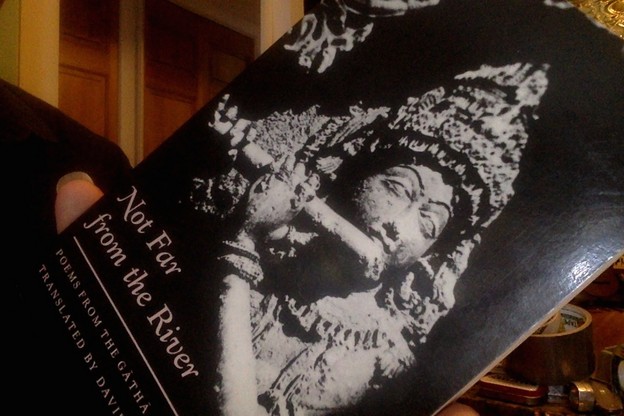

Bibliography: Not Far from the River: Poems from the Gāthā Saptaśati, translated by David Ray (Copper Canyon Press, 1990). ¶ Ray’s numbering for the items in his selection is simply sequential (1–356); it does not correspond with the numbering in Indian editions of the Gāthāsaptaśatī of Sātavāhana Hāla. However, I own a reprint of the Asiatic Society of Kolkata edition, which was Ray’s principal source-text. I’ll install a few items from this, for comparison’s sake, in an appendix.

The Gāthāsaptaśatī is supposedly the oldest extant anthology of secular poetry from South Asia, and is reputed to have been compiled by King Hāla in the 2nd century CE. The language is Mahārāṣṭri Prākṛt, the ancestor of modern Marathi.

58 items

[2]

Out of ten million or more gāthās

King Hāla has chosen a mere seven hundred.

The reason for this is quite simple—

he preferred those that caught life in their nets.

[4]

Rare sight, a woman lost in the trance,

making love. Beautiful—so long as her eyes

remain open, like blue of the lotus.

Then her pleasure gets ugly, too busy, intent.

[9]

The way of love is crooked and fragile

like the hair on a crab or a cucumber.

Therefore you fail to impress me, weeping

with your too perfect face, round as the moon.

[10]

Mother was angry. Father fell to his knees,

kissing her feet. I climbed on his back.

She broke into laughter, dragged him away.

Years later, I figure it out.

[20]

Doubly sorrowful, the loss of a lover

and seeing him involved with another.

Yet I honor his sense of high birth, his restraint

because he throws me not one glance of contempt.

[25]

Too many girls in this village

are thin from wanting him.

He’s cruel, afraid of his wife, elusive

and thin like a worm on a Nimba leaf.

[29]

She lives at the junction near the whores,

and her husband’s away.

She’s charming, youthful and ripe.

There’s no moon. Yet she won’t let me.

[44]

He’s gone on a trip, leaving his harem.

Already they’re friendly as sisters,

gossip all night,

bathe together at dawn in the river.

[46]

The wise are filled with inaction,

even in love,

while fools cavort to no purpose,

wrestling with love till it dies on them.

[59]

Love dies if you can't get to see her

or if you see her too much,

also from the gossip of vile men.

Or from no cause at all.

[63]

We enjoy your visits so much,

though knowing your words are deceitful,

that we think of the pleasure

of those whom you truly adore.

[67]

There’s one way to please,

be her slave.

Strangely enough it’s the proud men

who truly deserve our pity.

[73]

No one will listen to reason

when it comes to matters of love.

They seem to pause, seem to listen,

then the madness of love gets its way.

[78]

I remember this pleasure—

he sat at my feet

without speaking

and my big toe played with his hair.

[81]

Rare are those men

who don’t grow bitter with age,

whose serenity shows in their faces,

whose kind words are passed on to their sons.

[87]

The girl’s such a novice at love,

that she goes around saying

true lovers would die if they parted.

And she seems sincere.

[92]

Now that I see these dancers

I recall how much I enjoyed

that shampoo

you gave me with your feet.

[96]

Wicked men live like the good,

enjoy a family’s affection.

But they sully their walls

like defective lamps with foul smoke.

[100]

Here ends our first hundred gāthās,

written by all the best poets,

some of them wonderful lovers,

the others mere gossips and observers.

[112]

She’s new to it,

thinks there’s still more to come,

knows well how to begin an affair,

but not how to end it, wait for another.

[113]

Let the love of harlots be sanctified.

After all, like the dalliance

of true love, it relieves

both the deep thirst and the hunger.

[121]

There’s no one to love,

no one to tell all my thoughts.

And with whom would I share even a joke

in this wretched village of low people?

[126]

Only virtue, my boy, will win over

these ladies who cast oblique glances,

who talk with allusions, walk

in sly circles, smile before you do.

[131]

Awaiting him she trembles,

not knowing what she’ll do when he arrives,

or what she will say. And she fears

most of all she’ll have to do the work of it.

[153]

If you never managed a peek

take my word for it.

First she bathes in the sun

then makes love to herself in the shade.

[158]

Though the entire village burned down

we had the pleasure of seeing each other

still alive, our faces all flushed,

passing that scorched jug around.

[162]

She is so gorgeous your eyes become stuck

wherever you look—her arm, leg, belly.

No one can take in all of her beauty

because of this stickiness.

[163]

How can one woman manage it,

deadly as poison,

yet sweeter than nectar

as soon as you get close enough.

[173]

Lovers should be gentle always

because of the harsh facts:

Life is not eternal, and your love’s

pale skull waits beneath her skin.

[174]

Crows eat the ripe fruit of our village,

only the crows,

because of the watchful

love-starved old gossips.

[189]

I laughed when I saw it.

He fell to kissing her feet

and she drew the lamp near

as if to examine his foolishness.

[190]

Sometimes there’s a tax on virtue,

at least in this life.

One gives way, using the strength

from the past life, hope from the next.

[196]

O doer of a daring deed indeed,

I regret you can’t stay,

at least till my hair’s in a braid again

and my toes can uncurl.

[197]

In town he studied seduction.

Now he lures us one by one to his hut.

But none of his tricks can arouse,

leave us aglow like unplanned encounters.

[203]

Birds and men both

fill their bellies

with no concern for the poor and distressed.

But the best rescue others.

[215]

Most of the women of the world

are beautiful on one side only.

But she alone is perfect

both on the right and the left.

[227]

Quarrels leave debris in the mind.

Words said in anger linger for years,

rotten straw, along with foul secrets.

But all get consumed on the fire.

[228]

Who would dare look in her eyes,

bright as blue lotuses

till sharp pleasure closes them,

after they’ve trapped what they wanted.

[244]

Boys plucking flowers for puja

should avoid the banks of the river.

The gods have no use at all

for blossoms crushed on a lovebed.

[251]

Having chanced to glimpse two lovers,

the plowman’s son goes back to that spot,

gazes sadly upon it

as if he’ll never enjoy such a sport himself.

[270]

The wax-leaved ashoka tree bursts into bloom

if a beautiful woman kisses it.

But she stands shy,

afraid to be tested.

[277]

Only those women are happy

who have never laid eyes on this man.

They alone can sleep, hear what others say,

and not speak in faltering words.

[279]

He’s caught in the crossfire—

my scorn when he goes to you,

your fury when he’s back with me.

And yet we are sisters, or should be.

[288]

Men and women of bronze bear the fire

of Eros well, let it burn hot as hell.

Then there are those others—

consumed like paper with the first flame.

[289]

The clouds are grunting with effort

hoping to pull the earth up

on those millions of strings

strong as the best hammered silver.

[294]

When the lady’s on top

her hair’s a splendid curtain, swaying.

Her earrings dangle, her necklace shakes.

And she’s busy, a bee on a lotus-stalk.

[295]

O Krishna, you wander in our village,

make love with all manner of girls.

Only in this way, so you tell us, can a man

learn the difference between good, better, best.

[296]

How familiar the words.

But just once in a lifetime

a woman hears a man praise her

because unselfish love wells up in his heart.

[298]

When they stopped

she was embarrassed by her nakedness

but since she couldn’t reach her clothes

she pulled him on top of her once more.

[311]

Young men are so bitter about love

they won’t calm down, regard us as friends.

Believe it or not, each of these tea-drinking

old men once sipped at the poison of lust.

[316]

Take that damned parrot away.

He repeats all our love talk

to everyone in the village,

has them gathered around him.

[324]

It’s not the best river, perhaps.

Others have green banks, musical waters,

antelope near, look lovely.

But for love under water, ours is best.

[333]

He says she’s a whore, uses rough words

to describe what he’s seen through the reeds.

But if she did it with him

he’d speak of her sweetly—same woman, same tricks.

[350]

O clever and affectionate poverty,

how you love to cling to those

who are accomplished, liberal,

possessed of subtle, unbearable knowledge.

[356]

Our Prākrit poems end here, compiled

by King Hāla. Who could refuse to be moved

by their charm, or wish sincerely

we had held our tongues, speaking of love?

Appendix A: Specimens from The Prākrit Gāthā Saptaśati, Compiled by Sātavāhana King Hāla, edited with Introduction and Translation in English by Radhagovinda Basak (The Asiatic Society, Kolkata, 1971; reprinted 2010), keyed to Ray’s numbering, above.

[cf. Ray #2, above]

Out of one koṭi (ten millions) of gāthās (verses) adorned with alaṅkāras (ornaments or rhetorical figures of speech) seven hundred (only) have been collected (or compiled) by Kavivatsala (literally one who is compassionate towards the poets), Hāla.

[cf. Ray #4, above]

The amorous sports of women at the time of dalliance appear beautiful only so long as their eyes, resembling the petals of blue lotuses, do not become closed (in pleasure).

[cf. Ray #9, above]

O friend! Such is the way of this love which is as crooked (and fragile) as the hair growing on an infant crab (or, on the Karkaṭikā fruit, a species of cucumber). Do not (therefore) weep with your moon-like face turned round obliquely.

[cf. Ray #10, above]

When the (little) son climbed on the back of his father fallen at the feet (of his offended mother), a smile appeared even (on the face) of the householder’s wife, though feeling so poignantly afflicted by anger.

[cf. Ray #20, above]

Separation from the beloved and sight of the disliked person are both sources of heavy sorrows. But salutation be to (your) sense of high birth, (goaded) by which you act (towards myself).

[cf. Ray #25, above]

Oh son of the village-headman, so cruel, so afraid of your wife’s (mood), so hard to meet with, so resembling a worm in a Nimba plant! the whole village (i.e. the whole body of village girls) is yet getting emaciated on your account.

[cf. Ray #29, above]

Even the character of a woman, whose residence is on the junction of four roads and who is charming to look at, who is youthful and whose husband is abroad, and whose neighbors are unchaste women and who is herself indigent—is not (sometimes) dissolute.

[cf. Ray #44, above]

Only this day (our husband) has left home (for going abroad) and (it is found) that wakefulness of some persons (i.e. my co-wives) has evidently commenced this day, and the banks of the Godāvarī also have since this day become tinged with turmeric colour (of their toilet).

[cf. Ray #46, above]

I think that unfulfilled actions, with those (men) who understand the heart, produce as much happiness as fulfilled actions, with those of opposite nature, can not do [sic].

[cf. Ray #59, above]

Love disappears because of the absence of the sight (of the beloved), it also does so by frequent sights (of him), even it does so (again) by the gossip of vile men and (sometimes) it vanishes by itself (i.e. without a cause).

Appendix B: Two other translations of this material, both worth mentioning: (1) The Absent Traveller: Prākrit Love Poetry from the Gāthāsaptaśatī of Sātavāhana Hāla, selected and translated by Arvind Krishna Mehrotra (Penguin Books India, 2008)—contains versions of 207 gāthās, and (2) Poems on Life and Love in Ancient India: Hāla’s Sattasaī, translated and introduced by Peter Khoroche and Herman Tieken (SUNY, 2009)—contains the whole kit, divided up by theme.

Twenty-six items from Special Collections