Twenty-six items from Special Collections (j)

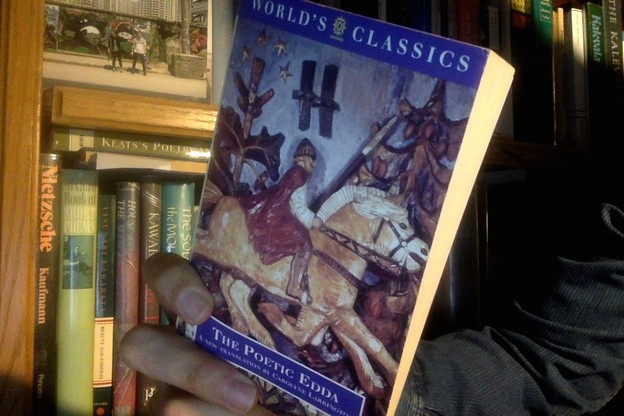

Exhibit 'J': medieval Icelandic. (Anonymous, excerpt from 'Hávamál' ['The Sayings of the High One'], from 'The Poetic Edda,' manuscript circa 1270 CE, stanzas 111–137)

Bibliography: The Poetic Edda, translated with an Introduction and Notes by Carolyne Larrington (Oxford University Press, 1996). ¶ A few words from Larrington's Introduction: "The Codex Regius, the manuscript in which the Poetic Edda is preserved, is an unprepossessing-looking codex the size of a fat paperback, bound in brown with brownish vellum pages; it is now kept in the Arnamagnæan Institute in Reykjavik. Most of the mythological and heroic poems it contains are only in this single manuscript.... In the 1270s, somewhere in Iceland, an unknown writer copied these poems down, preserving them as a major source of information about Old Norse myth and legends, and as a majestic body of poetry. [...] The Codex Regius remained in Copenhagen [from the middle of the 17th century] until the principal Icelandic manuscripts began to be returned to Iceland in the 1960s to be preserved in the Arnamagnæan Institute. Too precious to be risked in an aircraft at that time, the manuscript travelled back on a ship with a military escort, to be welcomed by crowds and public acclaim at the Reykjavik docks."

Comment: There is an interesting and perverse bit in Auden’s The Dyer’s Hand. I’m sure everyone who’s ever encountered it remembers it:

________________

Like Matthew Arnold I have my Touchstones, but they are for testing critics, not poets. Many of them concern taste in other matters than poetry or even literature, but here are four questions which, could I examine a critic, I should like to ask him:

“Do you like, and by like I mean really like, not approve on principle:

1) Long lists of proper names such as the Old Testament genealogies or the Catalogue of ships in the Iliad?

2) Riddles and all other ways of not calling a spade a spade?

3) Complicated verse forms of great technical difficulty, such as Englyns, Drott-Kvaetts, Sestinas, even if their content is trivial?

4) Conscious theatrical exaggeration, pieces of Baroque flattery like Dryden’s welcome to the Duchess of Ormond?”

If a critic could truthfully answer “yes” to all four, then I should trust his judgment implicitly on all literary matters.*

________________

* W.H. Auden, from “Making, Knowing and Judging,” in The Dyer’s Hand (1962), pages 47–48.

The above is stimulating on several levels. Number one, you can’t help being disappointed to find Auden would definitely not trust your judgment implicitly. Number two, it’s surprising a poet so concerned with truth and morals would make such a big deal out of stuff that has no moral (nor even intellectual) content. And then, three: there is the happy hint that all of us have these things—the opposite of “dealbreakers”—and if we had our own numbers like Auden had his, we’d be a lot better off. My homely phrase for this is: What are you a sucker for.

It will be obvious by now (to the five or six people who are following this sequence of exhibits) that I am a sucker for old-school repetition. I feel that a love for that is much more meaningful than a love for, say, rhyme, which I also adore. Rhyme—people love rhyme for all kinds of reasons, some of them quite offensive to my religion and upbringing. But anybody’s love for straight-up repetition I think I can trust.

For a long time I thought the excerpt below was my favorite part of Hávamál. It turns out everything depends on the translation. In my judgment, Larrington fairly nails the "Loddfafnir" stuff (stanzas 111–137), but the old Henry Adams Bellows translation (1936) makes the first section of the piece (stanzas 1–80) seem just as good. (Auden actually collaborated on a translation of all this same material [The Elder Edda: A Selection, 1969], but, curiously, the Auden/Paul Taylor version reads like homework.)

For the benefit of any geeks out there who want to recite the repeated bit in the original, I provide:

Ráðomk þér, Loddfáfnir, I advise you, Loddfafnir,

en þú ráð nemir, to accept advice—

nióta mundo ef þú nemr, you'll do well if you do—

þér muno goð ef þú getr it will be good for you if your get it ✝

_________________

✝ from The Poetic Edda, Volume III: Mythological Poems II, ed. with trans., intro. and commentary by Ursula Dronke (Oxford, 2011)

from The Sayings of the High One

[ . . . ]

It is time to declaim from the sage's high seat,

at the spring of fate;

I saw and was silent, I saw and I considered,

I heard the speech of men;

I heard talk of runes nor were they silent about good counsel,

at the High One's hall, in the High One's hall;

thus I heard them speak:

I advise you, Loddfafnir, to take this advice,

it will be useful if you learn it,

do you good, if you have it:

don't get up at night, except to look around

or if you need to visit the privy outside.

I advise you, Loddfafnir, to take this advice,

it will be useful if you learn it,

do you good, if you have it:

in the arms of a witch you should never sleep,

so that she charms all your limbs;

she'll bring it about that you won't care

about the Assembly or the king's business;

you won't want food nor the society of people,

sorrowful you'll go to sleep.

I advise you, Loddfafnir, to take this advice,

it will be useful if you learn it,

do you good, if you have it:

never entice another's wife to you

as a close confidante.

I advise you, Loddfafnir, to take this advice,

it will be useful if you learn it,

do you good, if you have it:

on mountain or fjord should you happen to be travelling,

make sure you are well fed.

I advise you, Loddfafnir, to take this advice,

it will be useful if you learn it,

do you good, if you have it:

never let a wicked man know

of any misfortune you suffer;

for from a wicked man you will never get

a good thought in return.

I saw a man fatally wounded

through the words of a wicked woman;

a malicious tongue brought about his death

and yet there was no truth in the accusation.

I advise you, Loddfafnir, to take this advice,

it will be useful if you learn it,

do you good, if you have it:

you know, if you've a friend, one whom you trust,

go to see him often;

for brushwood grows, and tall grass,

on the road which no man treads.

I advise you, Loddfafnir, to take this advice,

it will be useful if you learn it,

do you good, if you have it:

draw to you in friendly intimacy a good man

and learn healing charms all your life.

I advise you, Loddfafnir, to take this advice,

it will be useful if you learn it,

do you good, if you have it:

with your friend never be

the first to tear friendship asunder;

sorrow eats the heart if you do not have

someone to tell all your thoughts.

I advise you, Loddfafnir, to take this advice,

it will be useful if you learn it,

do you good, if you have it:

you should never bandy words

with a stupid fool;

for from a wicked man you will never get

a good return;

but a good man will make you

assured of praise.

That is the true mingling of kinship when you can tell

someone all your thoughts;

anything is better than to be fickle;

he is no true friend who only says pleasant things.

I advise you, Loddfafnir, to take this advice,

it will be useful if you learn it,

do you good, if you have it:

even three words of quarreling you shouldn't have with an inferior;

often the better retreats

when the worse man fights.

I advise you, Loddfafnir, to take this advice,

it will be useful if you learn it,

do you good, if you have it:

be neither a shoemaker nor a shaftmaker

for anyone but yourself;

if the shoe is badly fitting or the shaft is crooked,

then a curse will be called down on you.

I advise you, Loddfafnir, to take this advice,

it will be useful if you learn it,

do you good, if you have it:

where you recognize evil, speak out against it,

and give no truces to your enemies.

I advise you, Loddfafnir, to take this advice,

it will be useful if you learn it,

do you good, if you have it:

never be made glad by wickedness

but make yourself the butt of approval.

I advise you, Loddfafnir, to take this advice,

it will be useful if you learn it,

do you good, if you have it:

you should never look upwards in battle:

the sons of men become panicked—

you may well be bewitched.

I advise you, Loddfafnir, to take this advice,

it will be useful if you learn it,

do you good, if you have it:

if you want a good woman for yourself to talk to as a close confidante,

and to get pleasure from,

make fair promises and keep them well,

no man tires of good, if he can get it.

I advise you, Loddfafnir, to take this advice,

it will be useful if you learn it,

do you good, if you have it:

I tell you to be cautious, but not over-cautious;

be most wary of ale, and of another's wife,

and, thirdly, watch out that thieves don't beguile you.

I advise you, Loddfafnir, to take this advice,

it will be useful if you learn it,

do you good, if you have it:

never hold up to scorn or mockery

a guest or a wanderer.

Often those who sit in the hall do not really know

whose kin these newcomers are;

no man is so good that he has no blemish,

nor so bad that he can't succeed in something.

I advise you, Loddfafnir, to take this advice,

it will be useful if you learn it,

do you good, if you have it:

at grey-haired age you should never laugh!

Often what the old say is good;

often from a wrinkled bag come judicious words,

from those who hang around with the hides

and skulk among the skins

and hover among the cheese bags.

I advise you, Loddfafnir, to take this advice,

it will be useful if you learn it,

do you good, if you have it:

don't bark at your guests or drive them from your gate,

treat the indigent well!

It is a powerful latch which has to lift

to open up for everyone;

give a ring, or there'll be called down on you

a curse in every limb.

I advise you, Loddfafnir, to take this advice,

it will be useful if you learn it,

do you good, if you have it:

where you drink ale, choose the power of earth!

For earth is good against drunkenness, and fire against sickness,

oak against constipation, an ear of corn against witchcraft,

the hall against household strife, for hatred the moon should be invoked—

earthworms for a bite or sting, and runes against evil;

soil you should use against flood.

[ . . . ]

Twenty-six items from Special Collections