Twenty-six items from Special Collections (l)

Exhibit 'L': Sumerian. (Anonymous, ['In those days, in those far-off days…'], circa 1800 BCE)

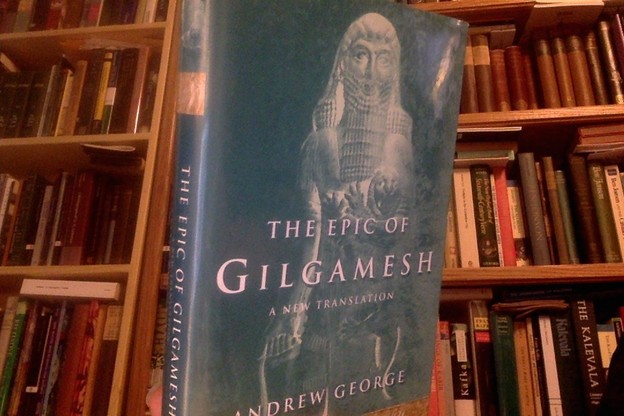

Bibliography: The Epic of Gilgamesh: The Babylonian Epic Poem and Other Texts in Akkadian and Sumerian, translated and with an introduction by Andrew George (Allen Lane The Penguin Press, 1999). The poem below and its editorial matter appear on pages 175–189.

Comment: The volume pictured above is the relatively hard-to-get first edition. Normal persons can simply order the Penguin Classics 2003 version: exact same text “with minor revisions.” The Gilgamesh in there is certainly worth the price of admission by itself, but it’s a shame people often miss the “Other Texts in Akkadian and Sumerian” that constitute the second half of the book. The specimen below is my favorite of these.

I want to underscore: the introductory material and the textual apparatus were both written by Andrew George, Professor of Babylonian, the translator of the work. They have their own charm, and so I have simply quoted them.

Bilgames and the Netherworld: "In those days, in those far-off days"

The poem known to the ancients as "In those days, in those far-off days" was also a favorite in the scribal schools of Old Babylonian Nippur and Ur. Unlike the other Sumerian tales of Bilgames, this composition begins with a mythological prologue: a long time ago, shortly after the gods had divided the universe between them, there was a huge storm. As the god Enki was sailing down to the Netherworld, presumably to take up residence in his cosmic domain, the Ocean Below (Abzu), the hailstones piled up in the bottom of his boat and the waves churned around it. The storm blew down a willow tree on the bank of the river Euphrates. Out walking one day, the goddess Inanna picked up the willow and took it back to her house in Uruk, where she planted it and waited for it to grow. She looked forward to having furniture made from its timber. As the tree grew it was infested by creatures of evil and Inanna was sad. She told the whole story to the Sun God, her brother Utu, but he did not help her. Then she repeated the story to the hero Bilgames. Bilgames took up his weapons and rid the tree of its vile inhabitants. He felled the tree and gave Inanna the timber for the furniture she needed. With the remaining wood he made two playthings (there is no consensus among scholars as to what these playthings were: one possibility is that they were a ball and a mallet).

Bilgames and the young men of Uruk play with his new toys all day long. The men are worn out by their exertions and their women are kept busy bringing them food and water. The next day, as the game is about to restart, the women complain, presumably to the gods (as in the Babylonian epic at Tablet I 73ff.), and the playthings fall through a hole deep into the Netherworld. Bilgames cannot reach them and weeps bitterly at his loss. His servant Enkidu volunteers to go and fetch them. Bilgames warns him about going to the Netherworld, the gloomy realm of the goddess Ereshkigal. If Enkidu is to avoid fatal consequences in the presence of the shades of the dead he must show the proper respect for them. He should behave as if at a funeral, acting with sensitivity and not drawing attention to himself. There in the Netherworld he will come upon the awful spectacle of Ereshkigal herself, who lies prostrate in perpetual mourning for her son Ninazu. The clothes torn from her body, she rakes her flesh with her nails and pulls out her hair.

Enkidu goes down to the Netherworld and blithely ignores Bilgames's warnings. He is duly taken captive there. Bilgames petitions the god Enlil in Nippur to help him but Enlil will not. He then petitions the god Enki in Eridu to help him. Enki instructs the Sun God, Utu, to bring up Enkidu's shade as he rises from the Netherworld at dawn. Temporarily reunited, Bilgames and Enkidu embrace. In a long session of question and answer that marks the climax of the poem Bilgames asks Enkidu about conditions in the Netherworld. The tone of brutal pessimism that informs this part of the text is relieved by a certain humour and sentimentality, and made topical, in one recension as least, by historical allusion. The principal message of the beginning of the heroes' dialogue is that the more sons a man has, the more his thirst in the afterlife will be relieved by the vital offerings of fresh water made periodically by his family. Those shades who are childless suffer worst, for nobody exists above on earth to make the necessary offerings to them. [...]

NOTE.

Square brackets enclose words that are restored in passages where the tablet is broken. Small breaks can often be restored with certainty from context and longer breaks can sometimes be filled securely from parallel passages.

Italics are used to indicate insecure decipherments and uncertain renderings of words in the extant text.

Within square brackets, italics signal restorations that are not certain of material that is simply conjectural, i.e. supplied by the translator to fill in the context.

An ellipsis (" . . . ") marks a small gap that occurs where writing is missing through damage or where the signs are present but cannot be deciphered. Each ellipsis represents up to one quarter of a verse.

Where a lacuna of more than one line is not signaled by an editorial note it is marked by a succession of three asterisks.

In those days, in those far-off days

In those days, in those far-off days,

in those nights, in those distant nights,

in those years, in those far-off years,

in olden times, after what was needed had become manifest,

in olden times, after what was needed had been taken care of,

after bread had been swallowed in the sanctuaries of the land,

after the ovens of the land had been fired up with bellows,

after heaven had been parted from earth,

after earth had been separated from heaven,

after the name of mankind had been established—

then, after the god An had taken the heavens for himself,

after the god Enlil had taken the earth for himself,

and after he had presented the Netherworld to the goddess Ereshkigal as a dowry-gift,

after he had set sail, after he had set sail,

after the father had set sail for the Netherworld,

after the god Enki had set sail for the Netherworld,

on the lord the small ones poured down,

on Enki the big ones poured down—

the small ones were hailstones the size of a hand,

the big ones were hailstones that made the reeds jump—

into the lap of Enki's boat

they poured in a heap like a surging turtle.

At the lord the water at the front of the boat

snapped all around like a wolf,

at Enki the water at the back of the boat

flailed like a murderous lion.

At that time there was a solitary tree, a solitary willow, a solitary tree,

growing on the bank of the holy Euphrates,

drinking water from the river Euphrates.

The might of the south wind tore it out at the roots and snapped off its branches,

the water of the Euphrates washed over it.

The woman who respects the word of An,

who respects the word of Enlil,

picked up the tree in her hand and took it into Uruk,

took it into the pure garden of Inanna.

The woman did not plant the tree with her hand, she planted it with her foot,

the woman did not water the tree with her hand, she watered it with her foot.

She said, "How long until I sit on a pure throne?"

She said, "How long until I lie on a pure bed?"

After five years [had gone by, after ten years had gone by,]

the tree had grown stout, its bark had not split,

in its base a Snake-that-Knows-no-Charm had made its nest,

in its branches a Thunderbird had hatched its brood,

in its trunk a Demon-Maiden had built her home.

The maiden who laughs with happy heart,

holy Inanna was weeping.

Day was dawning, the horizon brightening,

birds were singing in chorus to the dawn,

as the Sun God came forth from his chamber,

and his sister, the holy Inanna,

spoke to young Hero Utu:

"O brother, in those days, after destinies were determined,

when the land flowed with abundance,

when An had made off with the heavens,

Enlil had made off with the earth,

and he had given the Netherworld to Ereshkigal as a dowry-gift,

after he had set sail, after he had set sail,

after the father had set sail for the Netherworld,

after Enki had set sail for the Netherworld,

on the lord the small ones poured down,

on Enki the big ones poured down—

the small ones were hailstones the size of a hand,

the big ones [were] hailstones that made the reeds jump—

into the lap [of] Enki's boat

they [poured in a heap] like a surging turtle.

At the lord the water at the front [of] the boat

snapped all around like a wolf,

at Enki the water at the back [of] the boat

flailed like a murderous lion.

"At that time there was a solitary tree, a solitary willow, a solitary tree,

growing on the bank of the holy Euphrates,

drinking water from the river Euphrates.

The might of the south wind tore it out at the roots and snapped off its branches,

the water of the Euphrates washed over it.

I, the woman who respects the word of An,

I who respect the word of Enlil,

I picked up the tree in my hand and took it into Uruk,

took it into the pure garden of Inanna.

I, the woman, did not plant the tree with my hand, I planted it with my foot,

I, Inanna, did not water the tree with my hand, I watered it with my foot.

I said, "How long until I sit on a pure throne?"

I said, "How long until I lie on a pure bed?"

"After five years had gone by, after ten years had gone by,

the tree had grown stout, its [bark] had not split,

[in] its base [a Snake]-that-Knows-no-[Charm] had made its nest,

in its branches a Thunderbird had hatched its brood,

in its trunk a Demon-Maiden had built her home."

The maiden who laughs with happy heart,

holy Inanna was weeping.

Her brother, Young Hero Utu, did not help her in this matter.

Day was dawning, the horizon brightening,

birds were singing in chorus to the dawn,

as the Sun God came forth from his chamber,

and his sister, the holy Inanna,

spoke to the warrior Bilgames:

"O brother, in those days, [after] destinies were determined,

when the land flowed [with abundance,]

[when An] had made off with [the heavens,]

[Enlil had] made off with [the earth,]

and he had given the Netherworld [to Ereshkigal] as a dowry-gift,

after he had set sail, after he had set sail,

after the father had set sail for the Netherworld,

after Enki had set sail for the Netherworld,

on the lord the small ones poured down,

on Enki the big ones poured down—

the small ones were hailstones the size of a hand,

the big ones were hailstones that made the reeds jump—

into the lap of Enki's boat

they poured in a heap like a surging turtle.

At the lord the water at the front of the boat

snapped all around like a wolf,

at Enki the water at the back of the boat

flailed like a murderous lion.

"At that time there was a solitary tree, a solitary willow, a solitary tree,

growing on the bank of the holy Euphrates,

drinking water from the river Euphrates.

The might of the south wind tore it out at the roots and snapped off its branches,

the water of the Euphrates washed over it.

I, the woman who respects the word of An,

I who respect the word of Enlil,

I picked up the tree in my hand and took it into Uruk,

took it into the pure garden of Inanna.

I, the woman, did not plant the tree with my hand, I planted it with my foot,

I, Inanna, did not water the tree with my hand, I watered it with my foot.

I said, "How long until I sit on a pure throne?"

I said, "How long until I lie on a pure bed?"

"After five years had gone by, after ten years had gone by,

the tree had grown stout, its bark had not split,

in its base a Snake-that-Knows-no-Charm had made its nest,

in its branches a Thunderbird had hatched its brood,

in its trunk a Demon-Maiden had built her home."

The maiden who laughs with happy heart,

holy Inanna was weeping.

His sister having spoken thus to him,

her brother Bilgames helped her in this matter.

He girt his loins with a kilt of fifty minas,

treating fifty minas like thirty shekels.

His bronze axe for expeditions,

the one of seven talents and seven minas, he took up in his hand.

In its base the Snake-that-Knows-no-Charm he smote,

in its branches the Thunderbird gathered up its brood and went into the mountains,

in its trunk the Demon-Maiden abandoned her home,

and fled to the wastelands.

As for the tree, he tore it out at the roots and snapped off its branches.

The sons of his city who had come with him

lopped off its branches, lashed them together.

To his sister, holy Inanna, he gave wood for her throne,

he gave wood for her bed.

For himself its base he made into his ball,

its branch he made into his mallet.

Playing with the ball he took it out in the city square,

playing with the . . . he took it out in the city square.

The young men of his city began playing with the ball,

with him mounted piggy-back on a band of widows' sons.

"O my neck! O my hips!" they groaned.

The son who had a mother, she brought him bread,

the brother who had a sister, she poured him water.

When evening was approaching

he drew a mark where his ball had been placed,

he lifted it up before him and carried it off to his house.

At dawn, where he had made the mark, he mounted piggy-back,

but at the complaint of the widows

and the outcry of the young girls,

his ball and his mallet both fell down to the bottom of the Netherworld.

With . . . he could not reach it,

he used his hand, but he could not reach it,

he used his foot, but he could not reach it.

At the Gate of Ganzir, the entrance to the Netherworld, he took a seat,

racked with sobs Bilgames began to weep:

"O my ball ! O my mallet !

O my ball, which I have not enjoyed to the full!

O my . . . , with which I have not had my fill of play!

On this day, if only my ball had stayed for me in the carpenter's workshop!

O carpenter's wife, like a mother to me! If only it had stayed there!

O carpenter's daughter, like a little sister to me! If only it had stayed there!

My ball has fallen down to the Netherworld, who will bring it up for me?

My mallet has fallen down to Ganzir, who will bring it up for me?

His servant Enkidu answered him:

"My lord, why are you weeping? Why are you sick at heart?

This day I myself will bring your ball up for you from the Netherworld,

I myself will [bring] your mallet up for you from Ganzir!"

Bilgames spoke to Enkidu:

"If this day you are going down to the Netherworld,

I will give you instructions, you should follow my instructions!

I will tell you a word, give ear to my word!

Do not dress in a clean garment,

they would surely take it as the sign of a stranger!

Do not anoint yourself in sweet oil from the flask,

at the scent of it they will surely surround you!

Do not hurl a throwstick in the Netherworld,

those struck by the throwstick will surely surround you!

Do not hold a cornel rod in your hand,

the shades will tremble before you!

Do not wear sandals on your feet,

it will surely make the Netherworld shake!

Do not kiss the wife you loved,

do not strike the wife you hated,

do not kiss the son you loved,

do not strike the son you hated,

the outcry of the Netherworld will seize you!

To the one who lies, the one who lies,

to the Mother of Ninazu who lies—

no garment covers her shining shoulders,

no linen is spread over her shining breast,

her fingernails she wields like a rake,

she wrenches [her hair] out like leeks."

Enkidu paid no attention to the [word] of his master:

he dressed in a clean garment,

they took it as the sign of a stranger.

He anointed himself in sweet oil from the flask,

at the scent of it they surrounded him.

He hurled a throwstick in the Netherworld,

those struck by the throwstick surrounded him.

He held a cornel rod in his hand,

the shades did tremble before him.

He wore sandals on his feet,

it made the Netherworld shake.

He kissed the wife he loved,

he struck the wife he hated,

he kissed the son he loved,

he struck the son he hated,

the outcry of the Netherworld seized him.

[To the one who lies, the one who lies,]

[to the Mother of Ninazu who lies—]

[no garment covered her shining shoulders,]

[no linen was spread over her shining breast,]

[her fingernails she wielded like a rake,]

[she was wrenching her hair out like leeks.]

From that wicked day to the seventh day thence,

from the Netherworld his servant Enkidu came not forth.

The king uttered a wail and wept bitter tears:

"My favorite servant, [my] steadfast companion, the one who counselled me—the Netherworld [seized him!]

Namtar did not seize him, Azag did not seize him, the Netherworld [seized him!]

Nergal's pitiless sheriff did not seize him, the Netherworld seized him!

He did not fall in battle, the field of men, the Netherworld seized him!"

The warrior Bilgames, son of the goddess Ninsun,

made his way alone to Ekur, the house of Enlil,

before the god Enlil, he [wept:]

"[O Father] Enlil, my ball fell into the Netherworld, my mallet fell into Ganzir,

Enkidu went to bring it up and the Netherworld [seized him!]

My favorite [servant,] my steadfast companion, the one who counselled me—[the Netherworld] seized him!

[Namtar did not] seize him, Azag did not seize him, the Netherworld [seized him!]

Nergal's pitiless sheriff did not seize him, the Netherworld seized him!

He did not fall in battle, the field of men, the Netherworld seized him!"

Father Enlil did not help him in this matter. [He went to Ur.]

[He made his way alone to Ur, the house of Nanna,]

[before the god Nanna he wept:]

["O Father Nanna, my ball fell into the Netherworld, my mallet fell into Ganzir,]

[Enkidu went to bring it up and the Netherworld seized him!]

[Namtar did not seize him, Azag did not seize him, the Netherworld seized him!]

[He did not fall in battle, the field of men, the Netherworld seized him!"]

[Father Nanna did not help him in this matter.] He went to Eridu.

He made his way alone to Eridu, the house of Enki,

before the god Enki he wept:

"O Father Enki, my ball fell into the Netherworld, my mallet fell into Ganzir,

Enkidu went to bring it up and the Netherworld seized him!

[My favorite servant, my steadfast companion, the one who counseled me—the Netherworld seized him!]

Namtar did not seize him, Azag did not seize him, the Netherworld seized him!

Nergal's pitiless sheriff did not seize him, the Netherworld seized him!

He did not fall in battle, the field of men, the Netherworld seized him!"

Father Enki helped him in this matter,

he spoke to Young Hero Utu, the son born of Ningal:

"Now, when (as the Sun God) you make an opening in the Netherworld,

bring his servant up to him from the Netherworld!"

He made an opening in the Netherworld,

by means of his phantom he brought his servant up to him from the Netherworld.

He hugged him tight and kissed him,

in asking and answering they made themselves weary:

"Did you see the way things are ordered in the Netherworld?

If only you could tell me, my friend, if only [you could tell] me!"

"If I am to [tell] you the way things are ordered in the Netherworld,

O sit you down and weep!" "Then let me sit down and weep!"

"[The one] whom you touched with joy in your heart,

he says, "I am going to [ruin.]"

Like an [old garment] he is infested with lice,

like a crack [in the floor] he is filled with dust."

"Ah, woe!" cried the lord, and he sat down in the dust.

"Did you see the man with one son?" "I saw him." "How does he fare?"

"For the peg built into his wall bitterly he laments."

"Did you see the man with two sons?" "I saw him." "How does he fare?"

"Seated on two bricks he eats a bread-loaf."

"Did you see the man with three sons?" "I saw him." "How does he fare?"

"He drinks water from the waterskin slung on the saddle."

"Did you see the man with four sons?" "I saw him." "How does he fare?"

"Like a man with a team of four donkeys his heart rejoices."

"Did you see the man with five sons?" "I saw him." "How does he fare?"

"Like a fine scribe with a nimble hand he enters the palace with ease."

"Did you see the man with six sons?" "I saw him." "How does he fare?"

"Like a man with ploughs in harness his heart rejoices."

"Did you see the man with seven sons?" "I saw him." "How does he fare?"

"Among the junior deities he sits on a throne and listens to the proceedings."

"Did you see the man with no heir?" "I saw him." "[How does] he fare?"

"He eats a bread-loaf like a kiln-fired brick."

"Did you see the palace eunuch?" "I saw him" "How does he fare?"

"Like a useless alala-stick he is propped in a corner."

"Did you see the woman who had not given birth?" "I saw her." "How does she fare?"

"Like a defective pot she is cast aside, no man takes pleasure in her."

"Did you see the young man who had not bared the lap of his wife?" "I saw him." "How does he fare?"

"You have him finish a hand-worked rope, he weeps over it."

"Did you see the young woman who had not bared the lap of her husband?" "I saw her." "How does she fare?"

"You have her finish a hand-worked reed mat, she weeps over it."

* * *

"Did you see the leper?" "I saw him." "How does he fare?"

"His food is set apart, his drink is set apart, he eats uprooted grass, he roots for water (in the ground), he lives outside the city."

"Did you see the man afflicted by pellagra?" "I saw him." "How does he fare?"

"He twitches like an ox as the maggots consume him."

"Did you see the man eaten by a lion?" "I saw him." "How does he fare?"

"Bitterly he cries, 'O my hand! O my foot!' "

"Did you see the person who fell from a roof?" "I saw him." "How does he fare?"

"They cannot repair his bones.

He twitches like an ox as the maggots consume him."

"Did you see the man whom the storm god [drowned] in a flood?" "I saw him." "How does he fare?"

"He twitches like an ox as the maggots consume him."

"Did you see the man who did not respect the word of his mother and father?" "I saw him." "How does he fare?"

"He drinks water weighed out in a scale, he never gets enough."

"Did you see the man accursed by his mother and father?" "I saw him." "How does he fare?"

"He is deprived of an heir, his ghost still roams."

"Did [you see] the man fallen in battle?" ["I saw him." "How does he fare?"]

"His father and mother cradle his head, his wife weeps."

"Did you see the shade of him who has no one to make funerary offerings?" "I saw him." "How does he fare?"

"He eats scrapings from the pot and crusts of bread thrown away in the street."

"Did you see the man struck by a mooring-pole?" "I saw him." "How does he fare?"

"Let a man only say, 'O my mother!', and with rib torn-out . . .

The top part . . . his daily bread."

"Did you see the little stillborn babies, who knew not names of their own?" "I saw them." "How does they fare?"

"They play amid syrup and ghee at tables of silver and gold."

"Did you see the man who died [a premature] death?" "I saw him." "How does he fare?"

"He lies on the bed of the gods."

"Did you see the man who was burnt to death?" "I did not see him.

His ghost was not there, his smoke went up to the heavens.”

•

The version of the poem known at Nippur ends abruptly here.

Twenty-six items from Special Collections