Talking with Daniel Borzutzky

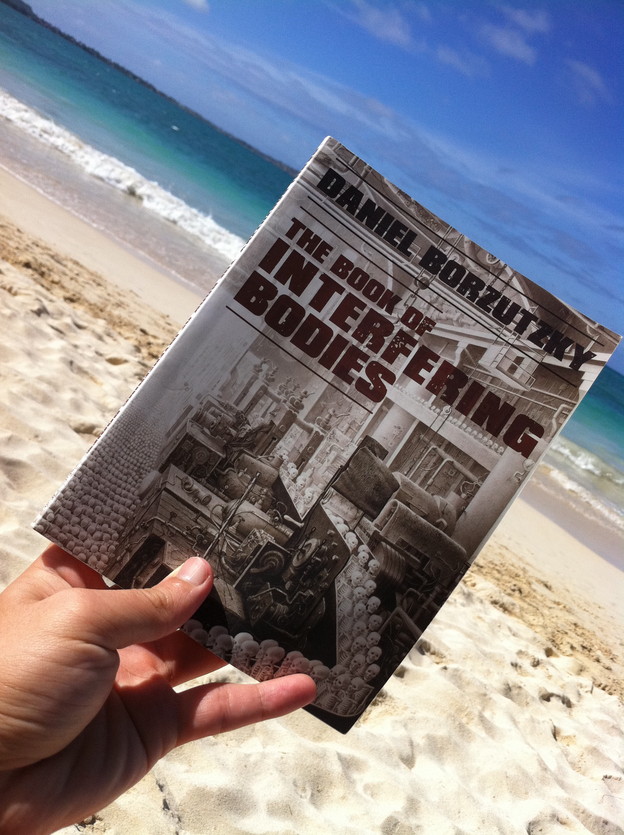

I love interviewing brilliant poets. Thanks to Daniel Borzutzky for his generosity in answering my questions about his new THE BOOK OF INTERFERING BODIES, currently on my beachshelf. Re-reading this interview, I realize that one aspect of the work that isn't mentioned is its humor. Yes, amidst everything else, this book is quite hilarious. Please share with your friends.

CSP: Your new work, THE BOOK OF INTERFERING BODIES (Nightboat Books, 2011), begins with a haunting epigraph from the 9/11 Commission Report: "It is therefore crucial to find a way of routinizing, even bureaucratizing, the exercise of imagination." Can you tell us a little about how you came across this passage and why you chose to quote it? Does it speak to your own aesthetics, or do you see your work as countering this routinization?

DB: The passage from the 9/11 Commission Report refers to an idea that was stated a lot after 9/11: that the failure to prevent the attacks on 9/11 was a “failure of the imagination.” This of course wasn't true. 9/11 wasn't a failure of the imagination. It was a failure of intelligence, but nevertheless this idea about failure of the imagination was presented as legitimate. I remember following this discussion about failures of the imagination, and thinking that, despite the misrepresentation of the 'failure,' that this was an interesting cultural moment – that the imagination was now being talked about publicly, that it was being taken seriously as something that was not just for children, and that the cultivation of the imagination was being linked to the public good and to issues of public policy and national security. This seemed very important to me at the time, though of course it was just a footnote to the many narratives that were going on in the aftermath of 9/11.

So when the 9/11 Commission Report was published in 2003 it had a section entitled “Imagination,” and this is where the book's epigraph comes from. I was pretty intrigued, again, by this exaltation of the imagination, and as a writer I'm also really interested in bureaucracies: how they function, why they function, how they fail, and how they affect individuals. To directly address your question: the combination of poetry and bureaucracy, of imagination and bureaucracy, completely speaks to my aesthetics, and I think it would probably appeal to those interested in the Oulipo and constraint-based writing as well.

Anyway, I read the quote with great interest and I looked in the rest of this section hoping to find suggestions for how the authors thought we might 'bureaucratize' the imagination. Sadly (I think), I didn't find any, which of course seems perfect, as a bureaucracy could only screw this up (but oh the possibilities!). The book started, then, as an attempt to figure out what it might mean to “routinize and bureaucratize” the imagination. I wanted to take this seriously, but the first attempts of doing this were more parodic and less successful. I remember I wrote a few pieces that were kind of like corporate training manuals for seminars on the bureaucratization of the imagination It was a good idea, but it wasn't really what I wanted to do.

To go back to your question, I wasn't at all trying to counter this bureaucratization and routinization. I was trying to figure out what extreme examples of this bureaucratization might look like, and that was the starting point for pieces like “State Poetry," "Failure of the Imagination," and "Bureaucratic Love Prevention Game."

There's a very cool short story called “The Ex-Magician from the Minhota Tavern” by the Brazilian writer Murilo Rubião, which ends: "I was forced to admit defeat. I had trusted too much in my powers to make magic, which had been nullified by bureaucracy." I feel like we're all pretty susceptible to having our magic, or our art, nullified by bureaucracy. But the Commission Report was suggesting that bureaucracy should develop the imagination in order to craft national security policy. The authors were missing the point about the imagination (it resists being bureaucratized), but the idea that it might be bureaucratized fascinated me, even though its execution was non-existent.

CSP: It seems like your work is definitely involved in resuscitating poetry’s power to shape the role of the imagination within the nation. With that being said, I must admit to being thoroughly disturbed by your work. The long Whitmanesque lines, coupled with the alternating prose poems, grabbed a hold of me and wouldn’t let go. I am haunted by lines like: “I peeled the skin off my chest and stomach and in my rib cage your voice said peel more / I peeled off my skin wishing to be what I would never become and you said forget and I forgot the name of my father, my mother, my country” (from “Resuscitation”). One strand of your work might be called “political grotesque,” a mode that explores the political through the grotesque (and vice versa). Can you tell us a little about this mode, refining it if you find “political grotesque” inaccurate. Either way, I’m curious about what draws you to these extremities of the body and of the body politic? Who are your influences in terms of this kind of work? What is the power of the grotesque in a post-9-11 America?

DB: I like what you say a lot in your first sentence, about resuscitating poetry's power to shape the role of the imagination within the nation. Clearly, I have no illusions that poetry can and will do this, but I very much want, at this moment at least, to be writing poetry that engages with questions of nation-defining, nation-constructing, and nation-imagining. And I think this has a lot do with my interest in Chilean writing, which I translate, and it perhaps has to do with my own background as a Chilean, a Chilean-American, whatever the hell I am.

Your question reminds me of a recent interview in Bookslut with Chilean poet Tomás Harris, whose excellent book Cipango, translated heroically by Daniel Shapiro, was published in 2010. Harris states that in Chile “poetry has permanently reexamined the process not only of how Chile became a nation, but also of Chile being a nation.” As exemplars of this idea, Harris then mentions Neruda, Mistral, and, among others, two poets I have translated: Raúl Zurita and Jaime Luis Huenún.

I don't read much of Whitman, though Neruda and Zurita, for instance, cite Whitman as an influence, and in particular I think it's his ambitious view of poetry as nation-defining that speaks to them (and I secretly like the idea that I'm influenced by Whitman, not through the U.S., but through Chile). Zurita is a writer who is immensely important to me. I love his work, his voice, and I am fascinated by, on one level, his focus on bodies, tortured bodies, disappeared bodies, surviving bodies, and on another level, his ability to fuse collective experience and individual trauma together to form poignant, beautiful and painful critiques of how authoritative bodies absorb and destroy powerless bodies.

Actually, in the poem you mention, “Resuscitation,” I was thinking a lot about a short story by Julio Cortazar called “Graffiti,” where a character in a police state spray paints a wall and then imagines a dialogue with another character who responds to his graffiti with additional drawings (the two artists never meet). The narrator imagines that a relationship forms between the two artists, in public, but also in secret, and thus the story exemplifies what communication is like, what relationships are like, what individuals must put up with, in order to speak with other individuals in the context of dictatorships and oppression.

The Book of Interfering Bodies also has several references to Marguerite Duras, for whom psychic pain and physical pain are indistinguishable. Her memoir, The War, about her time in the French resistance, and especially the part in the book where her partner returns from the concentration camps, includes some of the most horrifying scenes of physical decay that I've ever read. Jean Amery's writing about being tortured by the Nazis as well sticks out in my mind. Amery details what Elaine Scarry theorizes in The Body in Pain. He writes, “the more hopelessly man's body is subjected to suffering, the more physical he is...Pain is the most extreme intensification imaginable of our bodily being. But maybe it is even more, that is: death.” These lines lead to Beckett, whose Molloy, and whose writings about bodily decomposition are fundamental to me. Kafka, especially his short story A Report to an Academy, where Red Peter the ape is tortured into becoming a human being, and Thomas Bernhard, are other European writers who are important to me.

As I wrote Interfering Bodies, I was also really engaged with Clarice Lispector's writing, and totally obsessed with Juan Rulfo's Pedro Paramo, and his take on ghostliness, on being underground, on having mud in your mouth and being caught between the hopeless bureaucracies of a corrupt religion and a corrupt, repressive, excessively capitalistic state. In Rulfo, the revolutionaries are not much better; they're clownish and incompetent and thus his total rejection of ideologies on both the right and the left offers a useful position for a writer to occupy. So, my heroes here are mostly prose writers, and like a good Chilean-Eastern European-Jew I'm obsessed with a grouping of writers from both South America and the old world, all of whom are dealing, in their own ways, with bodies in pain, nationalism, torture, love, war, psychic trauma, decay and what it means to be an individual in a repressive nation or community. And they do all this with language that is so lively and beautiful that it demonstrates how art can, to paraphrase Fanny Howe, show that life is worth living by showing just how not worth living it actually is.

But in all this I've dodged the question of the “political grotesque,” which refers to an essay James Pate wrote in Action, Yes in which he coins this phrase and classifies myself, Lara Glenum and Ariana Reindes under this (PG) umbrella. Pate's idea of the “political grotesque” resonates with me for the simple reason that it provides a way of thinking about how a writer can respond to the political realities of her time. That is, the political violence of our time (e.g. state sponsored torture, endless war, the bombing of civilians and other “non-essential personnel,”), the social and economic violence of our time (e.g. the collapse of the global economy, the barbarism of corporate greed, American poverty and neglect of the poor, the war on unions and working people, the attacks on immigrants, on women, mass inequalities in access to food, water, education, health care, etc...) - these things are themselves grotesque. Thus if one sees the effect of politics and policy as grotesque then grotesque language and imagery is a way to craft a literary response.

Thus we return to the bureaucracy vis-a-vis the individual body. The bureaucracy is immune to how it affects the body. The bureaucracy, whether it be a political bureaucracy, a military bureaucracy, a religious or corporate body, must simply render invisible the individual body it destroys, or absorbs. I'd like to think that art can keep that individual body from becoming invisible, and to show just how grotesque the violence of greed, war, torture, etc.. actually is. Which isn't about realism. It's about trying to do with language what bureaucracies do with money and power, about trying to instill words with a similar, abject effect.

You ask what the power of the grotesque is in post 9-11 America. I have a lot of answers here, but I think I'll return to one of the other intentions in James Pate's essay on “the political grotesque,” which has to do with how easy it is to ignore the literal meanings of language, and how such an approach has become a common trope in poetry. As Susan Sontag so powerfully demonstrates in Illness as Metaphor, the language of disease, decay, and deterioration has historically been used to describe the plight of individuals and societies, and especially cities. But what's hiding behind the metaphors are actual suffering, wounded, starving, dying bodies whom it's very easy to not notice. The metaphors of illness cheapen the experience of those who are suffering the most. We're all stuck with the question of how we live amid this. In “Politics and the English Language,” George Orwell famously writes that political language is the defense of the indefensible. Perhaps, then, the political grotesque attempts to expose the defense-less body as it tries to survive in the bureaucracy of the indefensible.

CSP: Your work truly does invoke the “political grotesque” if I thought of it independent of Pate. I wasn’t sure how you would respond to such a categorization, but it seems from your response to Pate that the grotesque is en effective way to approach violent political realities. And I appreciate how Pate places you in conversation with Glenum and Reines (two poets I admire), and the genealogy you sketch of your aesthetic heritages locates you within a global aesthetic. All poets, too, responding to current and historical violences and trying to find way to embody the defense-less body—and perhaps to symbolically defend that body. Speaking of Action Books, I remember when I reviewed your translation of Huenun’s Port Trakl a few years back—and I’m looking forward to reading your translation of Zurita. Before I get back to asking you about the poems, I’m hoping you might tell us a little about how you became a translator. How does the process of translation itself influence your original work (aside from being influenced by the themes of the poet you are translating)?

DB: I have no training as a translator, and I know something but not very much about translation theory. One day, about ten years ago, I decided I was going to start translating and then I started translating, and since then my translation work has mostly focused on Chilean writers. A Chilean friend of mine introduced me to a fiction writer named Juan Emar from the 1930s (Emar is a pen-name that he took because it sounds like the French phrase “J'en ai marre,” which means “I'm screwed”). Emar hadn't been translated, and with my friend's help I started to translate him. I had a sense at the time that translation would be important for me and for my writing, but I didn't know how or why. It's turned out to be incredibly important.

How has the process of translation influenced my own writing? It's tough here to separate the process from the content, but I'll try. There's a certain combination of distance and intimacy that goes along with translating. No matter how much time you spend with the work, no matter how deeply you enter into it, it's not yours and it sort of is yours. Anyway, sometimes as I write I try to replicate this effect by positioning myself as a translator of my own writing, which I think of as part of the project of bridging the distance between me and myself, of bridging the distance between me and my other selves, or between me and the many voices that are at work at once as I write and think. I find it helpful to think that there are voices in my mind that are not my own (but are sort of my own) and that speak and think in different ways and that as a writer my task is to translate these thoughts and voices into some other voice in order to make my own work. It's a nice writerly task for me to imagine that I am stuck in the muck between me and myself, and that part of the task is to translate one part of myself so that it can be understood by others.

That's part of it. Another useful translation idea here is awkwardness. Translation, both dealing with the texts and dealing with the writers, their publishers, their estates, etc.. is inevitably a very awkward process. And as a translator it's sometimes helpful to try to not disguise those awkwardnesses, those awkward phrases that you could make “better” if you are willing to rearrange the author's original intent. In other words, sometimes as a translator it's helpful to expose the process of translation, of what's not so easy to translate, by making the text sound clunky. I sometimes like to do this with my own writing. I sometimes try to interrupt my own writing so that the process of translating myself doesn't go so smoothly, so that I make my own writing sound as if it is not able to fully communicate what it was intended to say, so that I bring out, and do not attempt to hide, those awkwardnesses in the communications between me and myself, bewteen myself and the world.

But there's another important and less comfortable identity discussion in all of this. As I mentioned, I am of Chilean origin though I have always lived in the United States. And in some ways it's been translation that has allowed me to work through the borders, both real and imaginary, that have been established between my life in the U.S. and the life I didn't get to live in Chile. There are several ways of seeing this. On one level, translation has allowed me to participate in the literary life of the world that was lost to me when my parents emigrated from Chile. But all of this is completely imaginary. By which I mean that the Chile I might have lived in, had it not been for certain historical realities, can be nothing but an unknowable mirage for me. And thus I have no illusions that translation has somehow made me more “Chilean,” whatever the hell might mean.

On the other hand, I do have some illusions about the imaginary spaces—both urban and pastoral---in this imaginary Chile, that translation has allowed me to occupy. Part of what it means to be a member of a nation is to circulate in both its real and imaginary spaces. And perhaps part of what it means to be a member of two nations is to allow for those real and imaginary spaces from both nations to intertwine. I like to think that translation has allowed for this to happen. And though this returns us to the content issue, I feel that in The Book of Interfering Bodies, and in some of my more recent writings, I am fusing Chilean horrors with United States' horrors, imposing disappearing bodies on a decimated, economically collapsed North American landscape, and in my mind I'm thinking about the multi-nationalist intertwining of neoliberalist initiatives and failures, with abuses of human rights and dignity.

CSP: My own awkward “translation” of your book would trace three major strands (or interferences): 1) the political grotesque poems; 2) the extreme bureaucratizing of the imagination poems; and 3) the meta-aesthetic grotesque poems. Since you’ve already discussed the first two, I’m hoping you might talk a little about the third set—I’m specifically thinking about the series of poems that all being with “The Book of…” (“The Book of Flesh,” “The Book of Graves,” “The Book of Broken Bodies,” “The Book of Collapsing Nations,” to name a few). I loved these poems for many reasons: they reminded me of the work of Edmond Jabes, they really articulated so many different (grotesque) visions and possibilities of the “Book,” and because they surprised me at every turn. Will you tell us a bit about how these poems emerged and developed?

DB: I wrote these “Books” in what was probably a 5 or 6 week period in the Fall of 2008. I wasn't sleeping very much. I'd get up really early and rush to bang out a draft of one of these in the morning before my son---who was one year old at the time---woke up. The global economy was collapsing and {the collective} we noticed but it was very easy to not pay attention. I remember a newspaper article about a 90-year old woman in Ohio who shot herself when the police came to serve her an eviction notice. There were other stories of people killing themselves because of the financial crisis. It was really easy to not pay attention.

Also, I was translating Raúl Zurita's Song for his Disappeared Love. Years ago, before I found this book, I had wanted to write about something I'd overheard: it was a story about a distant relative who supposedly had been thrown out of an airplane. I had no idea how to write about this. I couldn't write about it and my inability to write about it informed everything I did write. Then I read Disappeared Love by Zurita and his INRI. And there were suddenly approaches available to me to write about things that I thought I could never write about. And in Raúl's writing there was so much love and warmth amid the death and destruction. How was this possible? How could anger and love be so intimately fused not just in the poems' content but in their voices? I wasn't getting enough sleep. My writing had really changed since having a child. Before I had written funnier things. They were still political, about the world, engaged with war and violence and money and immigration and the emptiness of political rhetoric, but the approach was different. Before I could write with a certain lightness that I stopped being capable of. I think it has something to do with having a child, having a child amid all these other things.

And then I read this essay called “The Death of the Young British Pilot” by Marguerite Duras, in her great little book of essays called Writing. The essay begins as an investigation of a young British pilot from the second World War; he had been an orphan and had no family and was found dead in a tiny village in France. One of his British school teachers would come every year to put flowers on his grave. “He's a corpse, a twenty-year old corpse who will go on to the end of time.” And: “There should be a writing of non-writing. Someday it will come. A brief writing, without grammar, a writing of words alone...Lost. Written, there. And immediately left behind.” And: “If there weren't things like this, writing would never take place.” By “things like this” Duras meant anonymous, dead bodies that fall out of airplanes. If there weren't things like this writing would never take place. I knew exactly what she meant. It might be a fiction. It doesn't really matter. His parents moved overseas. They got a phone call one day. They were asked to fly to a mountain village to identify a body that had an identification card with their son's name on it. They flew across the ocean. Found their way to the mountain to identify the body. It wasn't their son. I have no idea if this is true. I've thought about it forever. It doesn't really matter if it's true. It's true even if it's not true. It was Fall 2008. The global economy was collapsing. One day there was a note in my mailbox at work that said: X called. She can't come to class today. Her brother was shot last night. I never saw X again. I had spent the Summer of 2008 trying to write a novel about a guy who is kidnapped, bound and gagged and forced to watch a website with video clips of people killing themselves in different ways. I tried to write the novel for several months. All I've ever wanted to write is a novel. I couldn't do it then. Some day I'll write a novel. It's as if in a long narrative I am unable to generate the intensity of rhythm and language that I am able to generate in shorter pieces. It's something about the mechanics of movement, of making things happen, of making people go from here to there.

So out of this failure came “The Books” from The Book of Interfering Bodies. I couldn't write the book I wanted to write so I started to write about the act of writing about the books I wished I could write. What we think is less important than our awareness of what we think. I think. Anyways, I started to write these poems called “The Book of Non-Writing," "The Book of Equality," Lovers, Graves, Interfering Bodies, etc...” I wrote 20 of them. There are 19 of them in Interfering Bodies. They appear in the book in the order that I wrote them. My favorite ones are at the end of the book. I probably should have put them at the beginning. The global economy was collapsing. I was reading Juan Rulfo at the time. I was reading Marguertie Duras. I was translating Raúl Zurita: “My boy died, my girl died, they all disappeared. Deserts of Love.” The voices of the ghosts were buried in holes, there was mud in their mouths, they were in purgatory or they were survivors and they needed their own books. I did my best to listen to them. I tried to write for them. I tried to write their books.

Last commentator in paradise