Reading Gabriela Jauregui's 'Controlled Decay'

Gabriela Jauregui was born and raised in Mexico City. Her creative and critical work has been published in magazines, journals, and anthologies in Mexico, the United States, and Europe. She graduated with an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of California, Riverside and holds an MA in English and Comparative Literature from the University of California, Irvine. She is a Paul and Daisy Soros New American Fellow and a PhD candidate in Comparative Literature at the University of Southern California.

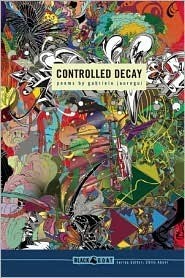

Gabriela Jauregui’s Controlled Decay (Black Goat, 2008) presents a dazzling range of theme, tone, and form. The book is divided into five sections: “Dust,” “Bone,” “Fat,” “Enamel,” and “Nail.” What holds the poems together is how their contents are ciphered through the poet’s real and written body. In this sense, the poems attempt to capture decaying bodies, decaying cultures, and decaying landscapes. By doing so, the decay is “controlled”—or at least held—in the space of the poem.

The very first poem, “Get On Down to the Floor to the Heaven of Other Animals,” puts the reader in the middle of the dance floor, of the threshing ground: “live music alive the music I like should beat beat beat me to you the space between nothingness is music” (21). Echoing T.S. Eliot’s “Burnt Norton” and Lorca’s thoughts on duende, this prose poem interweaves the rhythms of death and life, love and loss, body and spirit into a trance-like “cumbia del destino.” This emphasis on being alive is remixed in one of the many “loku” in the book: “deadlines / no more / here’s to lines alive” (36). Jauregui’s poetic lines are undoubtably alive lines. Another element that enlivens Jauregui’s rhythm is her interweaving of Spanish and English in various poems.

One of the most interesting poems in this book, “Collective,” details the speaker’s ride through the metro system in her home city of Mexico City: “and the city speaks multiple tongues babblecity Dear Dirty D.F. I am tongue-tied turn the turnstile get in come on take a ride on the metro” (77). As I turn the turnstile pages of this book, I am confronted at every turn with an astute lyricism. One example is “Cleavage”:

Tearing flesh from flesh

bares no heart

only a wound

pale and commonplace

alone

like a worm

who has lost the stars. (75)

There are quite a few shorter lyrics in this book (including many haiku and loku), attesting to Jauregui’s ability to express a more controlled and compressed poetry. These poems also provide a nice counterpoint to the more rhythmic prose poems and longer narrative poems. Another great example is “Instructions for Life”:

to achieve absence

radical invisibility

shatter into a million pieces

break so as not to bend

like cosmic bodies

colliding in space

be infinite

infinitesimal

a zero (30)

This short poem, reminding me of Alfred Arteaga’s work in Frozen Accident, stresses the importance of being open—both infinite and infinitesimal—to the rhythms of life and death. A similar poem, “Loku V” reads: “A woman is knot / not / naught” (126). In different ways, Jauregui locates the poet as perceiving subject within the vibrant “zero,” the knot of interiority and exteriority.

Some of the most powerful poems in this book addresses social decay and injustice, such as a mine explosion in Coahuila, Mexico; a train crash in Padre Burgos, Philippines; the Minutemen in Tombstone, Arizona; the Tlatelolca student massacre of 1968 in Mexico City; the murder of Lebanese activist and journalist Nayla Tueni; and the cultural destruction of the Ishir Peoples of the Paraguayan Chaco by a group of missionaries called New Tribes Mission. Jauregui doesn’t just narrate the stories of these historical moments, but she presents a striking and lyrical portrait filtered through the poet’s perceptions. In “And Benito was a Lawyer from Oaxaca,” Jauregui describes the tragedies and horrors of feminicide in Ciudad Juarez:

slit

is my throat

my slit

filled with silt

a river dries

my hair

Irene Silvia Mercedes saints in the desert

blind

bonedry

flow

nowhere

no place for slits

and lipstick lips

mujer muerta (33)

The poem ends by pointing to the irony that Ciudad Juarez was named after Benito Juarez, Mexico’s beloved leader. The speaker asserts: “he would feel far away from home in this city named after him / amongst the corpses of his granddaughters / slits endless / like mouths crying home / crossed out” (33). Another poem, “Fresa,” begins with the speaker’s mother telling her that she shouldn’t eat strawberries. The poem explores the various semantic and literal (California) landscapes where strawberries are produced. The poem ends with a striking image:

In Strawberry, CA

methyl bromide

covers hands

and pumps

into arteries,

into red, red fruit,

to make it strong.

Poison and dirt

and red blood.

No matter how much

you wash them,

it won’t come out. (108)

The poems in this strand of socio-political poems culminates in “After Goya (and Fallujah and Kigali and Juarez and Da Nang and Wounded Knee and Tiananmen and Cali and Compton),” which begins: “There are / bodies upon bodies upon bodies upon bodies upon bodies / inside my pen” (83).

Controlled Decay is a powerful first book that shows the range of Jauregui’s talents and concerns. She shows both a compelling sense of musicality with an undeniable ability to control image and line. Her poetry is centered in the knotted zero of a woman’s body, where external injustices inflict the body viscerally. Jauregui transforms these inflictions into a mouth uncrossed out and shaped into song.

Last commentator in paradise