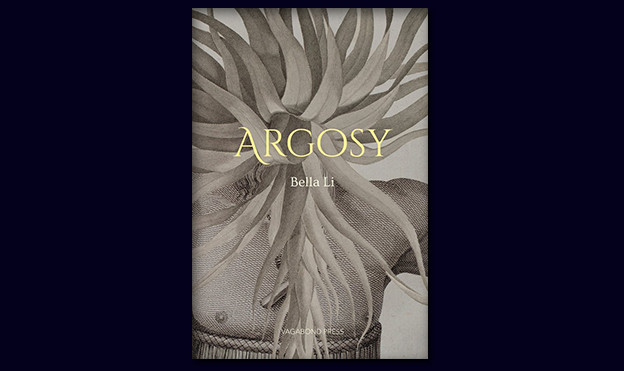

Sea shells and torsos in Bella Li’s 'Argosy'

Sometimes writing poems is too much for me. I’ll be in no mood for words or for thinking with any depth on a matter. I cut and glue pictures and patterns instead. Collage is how I shift gears. There is something peaceful about cutting along the edge of an image. I have books on magic and mysteries of the world and Jane Fonda’s workout routine and children’s illustrated history books and books about space and land and science. I have folders where images and landscapes wait for me to find a use for them.

I can follow my amateur (nonexistent) visual sensibilities as I piece together the cut-out phrases and headless bodies and mollusk shells, and it brings me simple pleasure. There are no painstaking decisions to make or moments where I completely shut down and question every decision I ever made leading up to this point. Collage-making, for me, requires an embrace of making mistakes. Every fuck-up can also be intentional. Every aesthetic decision must first feel intuitive or at least fit my mood that day.

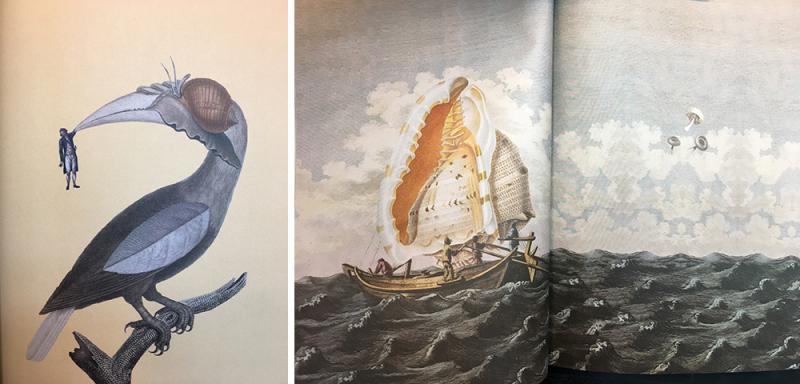

This casual attitude and flippancy is nowhere to be found in Bella Li’s Argosy collages. Not to say that there is no intuition behind it, but that she blends her intuition with careful consideration of the language she is producing. The artworks Li combines (shells, bodies, ships at sea, colonial illustrations, plants) are thematically unified and aesthetically pleasing, while also raising questions for the reader to puzzle over and unpack. They knit together their elements in a manner that feels seamless, but requires a deep engagement with the text in order to make meaning from it. The book models itself from Max Ernst’s collage novels (Une semaine de bonté: A Surrealistic Novel in Collage and La femme 100 têtes), and draws upon the materials of other Surrealist texts as well as a variety of sources — films, contemporary interviews with living authors, journals, poems. It finishes with a photography series by Li. It is printed on a paper stock that is sturdy but covered in a soft fuzz, so that when your fingers make contact with it, you wonder whether they are even touching another surface or imagining it.

The collage sequences position seashells, butterflies, and animals atop eighteenth- and ninenteenth-century explorer sketches from La Pèrouse, de Labillardière, and D’Urville and, later in the pages, layers sewing pattern illustrations onto the author’s own photographs.

Combined, these various materials that Li has gathered become a new wild object, a declaration about how poetry can look and be. Or, at least, what a non-narrative exploration of colony and nature might look like.

I’ve been working on my own book-length poetry project for some time and have toyed with how I might incorporate collage work into it. Reading Li’s book made me realise this incorporation needs to be central to the project itself, rather than an element to add to the poetry. Her prose poem sequences that appear in between the image sections play with quiet and fantastical visual scenes (‘Through the blaze I step with eyes closed, but o — what beast sinks its weight inside the skin. The blood beats. These small fires.’) and movement, such as in the section jeudi: LES RÊVES, which ends each page with the refrain: ‘you move’ (and, occasionally: ‘you do not move’.).

I read over and over again this line: ‘I have loved you like the knife’.

pics & illos &c.