Major authors

When I first began teaching in the MAT program at Bard in 2011, I was asked to propose a graduate course based on the standard areas of study within the literature track, which includes a “major authors” course. I had just completed a dissertation on gender and American poetry after 1945, in which all my major figures were marginalized women poets but in which I had frequently turned to Williams as the major figure of masculine modernism to whom many poets writing after 1945 turn — and away from whom they turn, also. I had become increasingly fascinated with literary inheritance and disavowal, and how theories of gender and identity might help us understand how poetic form behaves genealogically. I kept coming back to Williams as a beloved and contentious figure for American poets both major and marginalized.

In her 1980 lecture “Doctor Williams’ Heiresses,” for example, Alice Notley writes, “Gertrude Stein & William Carlos Williams got married: their 2 legitimate children, Frank O’Hara & Philip Whalen, often dressed & acted like their uncle Ezra Pound. However, earlier, before his marriage to Gertrude Stein, Williams had a child by the goddess Brooding. His affair with Brooding was long & passionate, & his child by her was oversized, Charles Olson.” Notley rewrites the genealogy of American poetry by playing with traditional laws of reproduction, feminizing male bodies and mating poets of different generations. And her piece centers around Williams, to whom she alternately rages and speaks indebtedly and lovingly.

So I chose to organize a major authors course around Williams, because he had already served as a figure who helped me coalesce variant concerns around modernism, gender, and poetic form. I chose him also because of his popularity in the secondary school classroom: I imagined many robust debunkings of the pat canonization of “The Red Wheelbarrow” with my student-teachers in training, who would now see that quintessential lyric within all the complexity and strangeness of Spring and All. And I chose Williams because he leads us to many other authors who populate my syllabus, from Poe to Spicer to Notley to Bernadette Mayer.

Now that I approach teaching this course for a second summer, I’m thinking even more this time around the politics of the major author study. A web search turns up this line from an English Major Worksheet at the University of Hawai`i at Manoa:

If a course is used to fulfill the Single Author requirement, it may not be used to fulfill an Historical Breadth requirement.

Does the Single (or Major) Author course sacrifice Historical Breadth? And yet isn’t it supposedly History that determines who are the Major Authors?

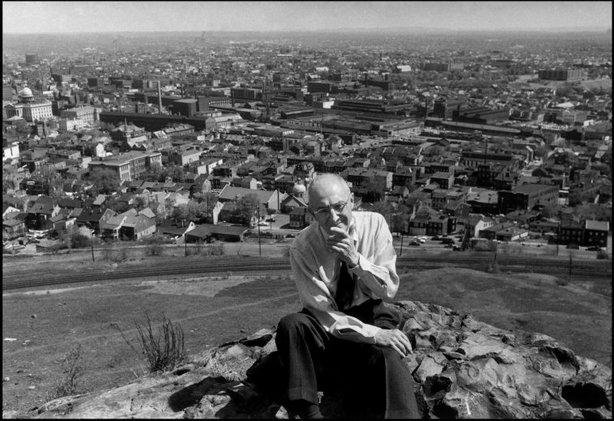

Against the weather: On teaching Williams