Double entry

I recently asked my students to engage in a “dialectical journal” activity in our William Carlos Williams class. There are many examples online of what teachers refer to as a “dialectical” or “double entry journal,” in which students use multiple columns on a page to react to specific phrases and passages from a text. The dialectical journal is a popular tool in secondary schools and undergraduate curricula, and ranges from the relatively simple act of gathering reactions to a text to more complex methods of translating reactions into critical assessment and reflection — visual connections, social questions, naming literary techniques, generating a thesis. Essentially, the dialectical journal is a physical template for the kinds of annotating and close reading we do all the time: a kind of spreadsheet to track what different parts of the text are doing, and what kinds of reactions we have to them. What I found in the Williams class, however, is that there is something even more dialogic going on than creating a conversation between readers: the genre of the text seems in some ways to determine the form of the reader’s own writing.

I was introduced to the journal in erica kaufman’s Institute for Writing and Thinking workshop this summer, where the directions were straightforward:

1. Break up into groups of 3. Each person finds a quote in a text you’re reading.

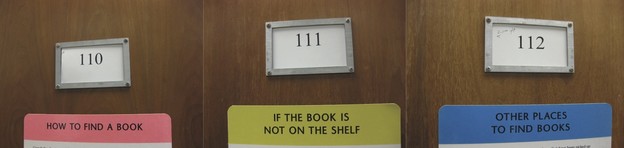

2. Turn your notebook horizontally, copy the quote into your notebook, and draw three vertical lines so that you have four columns in your notebook. The top of the page looks like a version of this:

writer | responder 1 | responder 2 | writer

3. Spend a few minutes responding to your quotation in the first column. End your writing with a question.

4. Pass your notebook to the right. Your classmate will spend a few minutes writing in the second column in response to your quote, response, and question.

5. Pass the notebook to the right again. The next member of your group reads the first and second columns and responds in the third column.

6. Return the notebook to the writer, who then responds in the fourth and last column to everything that’s been written.

In the IWT workshop, we worked with George Orwell’s “Why I Write,” in which Orwell argues:

I think there are four great motives for writing, at any rate for writing prose. They exist in different degrees in every writer, and in any one writer the proportions will vary from time to time, according to the atmosphere in which he is living. […] [N]o book is genuinely free from political bias. The opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.

I chose the last sentence from the above excerpt as my quote. My group members and I filled up four columns with a debate about aesthetic value and political bias: how much are they opposed, and where do they overlap? Is political writing good writing, or are the two qualities different? What is art? Is all writing political? We were using writing techniques derived from Peter Elbow’s Writing with Power, in which you write in response to someone else’s language, so we responded to one another’s specific points as well as tone. The writing that filled up my notebook was both informal/associative and analytical: everything from “I actually think Orwell is full of it” to “‘Age’ can refer both to historical epoch and to the writer’s biography.” We were glib and we were critical, but we pretty much remained on topic. During discussion afterward, we found most people in the group chose similar quotes that spoke to Orwell’s central argument about politics.

In the Williams class, we used the dialectical journal to write about Tristan Tzara’s “Dada Manifesto 1918.” I had originally planned to use it with Pound’s “A Retrospect,” but our conversation had already taken us so deeply into that text that I wanted to tackle something new.

Writing collaboratively, in silence, took us far into the text in a way that discussion can’t. Students reported that they felt much less alienated from the manifesto than they had upon first reading it, and that they had come to appreciate its odd format. Some found it essentially nihilistic, others simply humorous; all agreed the time we spent writing (nearly an hour) gave us entry into the manifesto’s multiple meanings. I had expected that some of this might happen. But what I didn’t expect is that the journal would work so differently with the Tzara than it did with the Orwell. For one thing, there was no overlap in the quotes chosen, which suggests that no one passage dominates the whole as the ‘key’ to reading Tzara’s text. For another, dialogue within groups was more meandering, at times even chaotic, filled with questions and declarations. We sounded Dadaist.

This makes me wonder how the rules of genre carried over into our notebooks. Orwell’s piece is classic essay genre: discursive and wandering, but aimed at a single point of argument. Tzara’s piece follows the rules of the manifesto genre, one might even say more so: it repudiates logic, offering caricature and irony where other modernist writers of manifestoes (like Pound) are perhaps more essayistic even as their language is polemical.

In a way, Tzara’s manifesto is also a meta-manifesto that uses its form to comment on the genre itself. My quote from Tzara was the last four words of this passage:

I write a manifesto and I want nothing, yet I say certain things, and in principle I am against manifestoes, as I am also against principles (half-pints to measure the moral value of every phrase too too convenient; approximation was invented by the impressionists). I write this manifesto to show that people can perform contrary actions together while taking one fresh gulp of air; I am against action; for continuous contradiction, for affirmation too, I am neither for nor against and I do not explain because I hate common sense.

Janet Lyon writes in Manifestoes: Provocations of the Modern that Tzara’s manifesto is a kind of “exfoliation of the manifesto form,” one that uses the manifesto genre to teach us something. She writes:

The manifesto is a pedagogical vehicle, he implies: it teaches us fundamentals, little abcs and big abcs. It is a form marking the contours of rage, and it deploys the verbal accoutrements of rage — shouting and swearing and fulminating. It is a testament of “proofs,” marshaling arguments and conquering disbelief in the name of proof. (41)

The dialectical journal is its own kind of genre, perhaps one that mimics the genre of its source texts. If Tzara’s manifesto is pedagogical, we were its students, and with the dialectical journal we wrote into and through the lesson. (Jameson, dialectic, and genre theory would seem to be the next step in this discussion.)

Against the weather: On teaching Williams