Facsimile again

Pt. 1

In the last decade or so, the proliferation of digital technologies has created an unprecedented interest in the art of the book, its history and culture, what William Everson called ‘the book as icon,’ and yet I’m not entirely convinced that people are reading more in the poetic sense of the word, that is, more deeply, broadly, tactfully, consciously, skeptically—dare I say imaginatively? Typographic literacy has endured a parallel proliferation as well, and while it’s anyone’s guess how to interpret the domestication of the black art now that any office worker can discern between Times New Roman and Georgia or sans serif fonts like Helvetica and Ariel, the knowledge is clearly out there. In turn, bookstores are vanishing, funds for public education are all but nonextant, and the homeless and unemployed are the most loyal patrons of the public library. The means and definitions of literacy are changing and shaping what and how we read more vigorously than we may realize, complicating the role of the author as producer, cart and horse alike.

Remember when the posture of the city changed? Look at a crowd of people walking down a busy street in the mid-nineties and note that their arms are by and large at their sides. Fast-forward ten years to the same street, and note how the elbow and torso form a ninety-degree angle meeting at the shoulder. The same figures are asymmetrical, speaking to no one, laughing uproariously at nothing in particular, as if a cloud inducing schizophrenic tendencies had silently settled upon the city. It’s the pulp of science fiction, and not surprisingly, exactly what happened when the cell phone became commonplace. And now the cloud is clear, and it’s rather ethereal (aether-real): it’s where our information goes so it can survive after the body, or hard drive, dies. It is always with us, wherever we are, whenever we need it, providing solace and eternal life.

In the recent past, the park between the subway and the apartment was a place to unplug, stretch, breathe, and then it became a place to return the calls one missed on the subway where there was no reception. But that was 2005, before the smart phone replaced the cell phone. Fast-forward five more years, and the phone rarely rings, and yet for most people, it is the single most important appliance they own, the thing they cannot live without. As the telephone matured, the telephone call became obsolete, perhaps even crude and abrasive, rather than humanizing and live. The unannounced telephone call is perceived as something strange, direct, even intrusive, even if it comes from someone you ‘talk’ to regularly on e-mail or FaceBook. The common etiquette now dictates that we text or FaceBook someone, even a close friend or family member before calling: Can we talk sometime this weekend? Phonephobia. Moreover, with the advent of the smart phone, the posture changed again, and in spite of their ‘connectedness’ people quieted down, and appeared more isolated and unaware of their surroundings. The smart phone gave the arm permission to returned to the side of the body, but it bent the neck forward awkwardly creating a hunch while the fingers hover spastically over a touch-sensitive screen cupped in mousy hands automatically darting from one app to the next. The glow follows us wherever we go.

The frenzy of activity spurred by the fusion of social media and the smart phone has made the idea of private correspondence, personal and professional life, mass media, and even the boundary between interior and exterior lives uncertain, at best. The experience of seeing a concert is secondary to the act of recording it, commenting on it, broadcasting and asserting one’s presence, as if to prove ‘I was there.’ When I accompanied a friend to a Beirut concert in Williamsburg I noticed that the smart phone replaced the cigarette—instead of holding up lighters during the encore, the pop singer looked out over a sea of illuminated cell phones. Where people once smoked to pass the time between activities, like arriving at a bus stop and the arrival of the bus, they fidget with their phones. They’re ‘doing something.’ McLuhan saw it coming. Susan Sontag and Paul Saffo too. And while it may appear that I’m going down the luddite’s dirt road to the land of peace and plenty, I would argue that the impetus for compulsively Tweeting at a concert satisfies an important, if not innate, part of human nature that has persisted since the beginning of writing and art itself—consider the recently unearthed Aboriginal work of art created 28,000 years ago in an Outback cave in the Northern Territory rock shelter known as Nawarla Gabarnmang. The desire to read and write, be it with charcoal or an iPhone, share in the same desire to understand and be understood, to communicate in and across time, to augment perceptions of the past, present, and future.

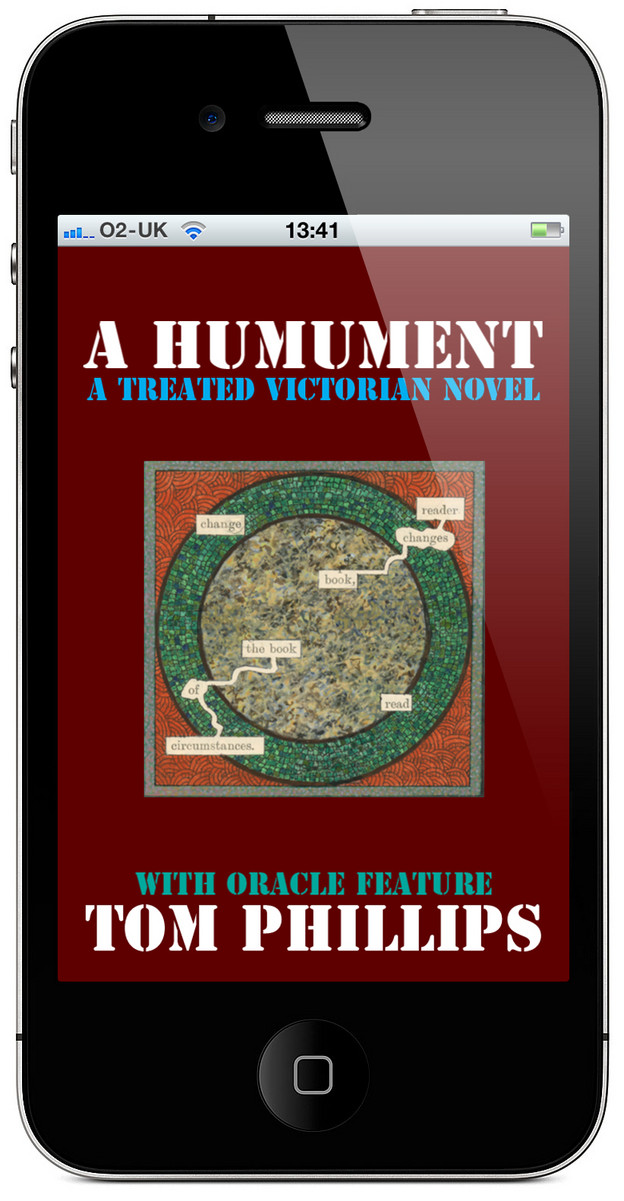

A friend of mine broke her leg when she stumbled down the subway steps reading Ulysses on her iPhone on Bloomsday. Another friend’s seven year old autistic son has dazzled me with his intimate knowledge of Tom Phillip’s Humument thanks to the iPad app. Look in the business section of The New York Times any day of the week and you’ll find an article about publishing. In turn, ask anyone on the bus for his or her opinion about e-books, the future of the library, or the effect of new media on cultural literacy, and you’re bound to get a strong response. Debates about publishing and the future of the book have never been more commonplace, provocative, complex, or uncertain than there are right now, and there’s never been a more interesting time to engage with the art of the book.

To be continued...

Kyle Schlesinger

06.23.12

Book arts