Eliot Weinberger on Omar Cáceres

From Jacket #3 (April 1998)

All the stories from the capitals have grown familiar, but where are the histories and accounts of modernism as it was lived and practiced in the provinces? Latin America, for example, in the first half of the century, has shelves of unwritten magical realist literary biographies: The Peruvian Martín Adán, whose first book made him famous at twenty, and who then checked himself into an insane asylum, where he lived for another sixty years, writing on scraps of paper he threw away that were dutifully collected by the orderlies and sent to his publisher. Jorge Cuesta, a poet and the leading Mexican critic of the 1930’s, who castrated and slowly fatally poisoned himself as part of his alchemical experiments. Carlos Oquendo de Amat, a Lima street kid who published one book, 5 Meters of Poems, on a folded sheet of paper five meters long, then gave up writing to join the Communist Party, and bounced in and out of jails and tuberculosis wards in a half-dozen countries before dying in Spain just before the civil war. Joaquin Pasos, a Nicaraguan who also died young, who wrote Poems of a Young Man Who Has Never Traveled about the places he hadn’t seen; Poems of a Young Man Who Has Never Been in Love, which are all love poems; and Poems of a Young Man Who Doesn’t Speak English, which were written in English. Felisberto Hernández, a writer of stories unlike any others, more associative than narrative, who lived with his mother and wrote in a windowless basement, who paid for the publication of his books by playing the piano in bars in the Uruguayan hinterland, and who died so fat the funeral home had to remove a window to get the coffin out.

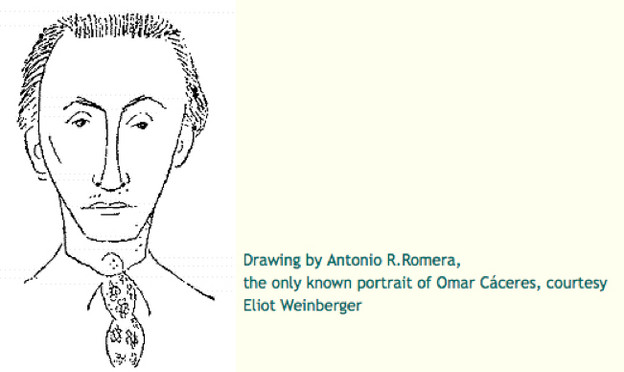

And Omar Cáceres: A Chilean, born in 1906, who worked as a violinist in an all-blind orchestra, of which he was the only sighted member. In 1933, hearing that a group of young poets was meeting in a café‚ to put together an anthology of the new Chilean poetry, he walked in, waited until one of them was alone, gave him a poem, and left. The group wrote him, asking for more work, and he agreed to meet on a busy street corner. He handed over a manuscript and kept walking — a tall, thin figure with empty eyes and the ‘elegance of a ghost,’ as one of the poets, decades later, recalled.

[read more of this article from Jacket #3]