Death's great black wing

'Mi say mi cyant believe it'

Everything is plundered, betrayed, sold,

Death’s great black wing scraped the air,

Misery gnaws to the bone.

Why then do we not despair?

— Anna Akhmatova

June 5, 2020

Dear Claire,

“Mi say mi cyant believe it” — in the words of the brilliant Jamaican dub poet, Mikey Smith. I began this two days ago and even since then so much has changed and, frankly speaking, I don’t know where to start to bring you up to date. Given that you’re in heaven — poet’s heaven, you probably know all that is happening, so do forgive the explanations and digressions as I try to follow my thoughts and emotions in these very difficult times. I’m also trying to imagine what being in poet’s heaven must be like — have you met Emily yet? — put us ahead of the Sun, she did, and Summer and even the “Heaven of God,” and then doubled back and said that we poets were all those things and more — “Poets—All.” Ha! I imagine you having tea with her, and Audre, perhaps, and having her Black cake and talking about our present hell on earth.

I wrote this entire letter to you — some fifteen pages — longhand; am now typing it up and, of course, changing it. Do you remember we talked of writing longhand to each other when we started our correspondence. You said it had to be a proper correspondence. I love the drag of a pen against a page, wonder if the iPad Pro — you can actually write on the screen — creates such a feeling. The traction slows my thoughts to a more reasonable pace. That was such a long time ago, our correspondence, and by the way, you still have my book, Infidel. I recall you said, when I asked you about it, that your mental challenges were such that you could reread a book and it felt like you had never read it before and so you could enjoy it over and over again. Odd that I mention that because I just posted a poem on FB — “Blackman Dead” — and had a different but uncannily similar experience as you describe — a sort of Groundhog Day observation, which I’ll try and explain later — recently I find myself reaching for words to describe feelings and emotions in the mayhem that’s all around me now, and much as I’ve been trained in, and appreciate, the virtues of a sweetly reasoned argument, I cannot reason this — this … time, these emotions, these thoughts away — I cannot approach it in the calmly dispassionate ways in which the Europositive schools and ways of thought have disciplined me. This is not a desire to be irrational, but I do believe that emotions have their own kinds of reason — the heart has reason as much as the brain; the gut its own way to making sense of phenomena. It is we who have lost the map. I started out writing about what was happening in the way I’ve approached the previous commentaries (three so far) — that way being approaching it as another topic for the blog on COVID-19 that I committed to doing over several weeks. My early attempts at this particular one felt dead — there was no connection to what I was feeling — raw, as if there was a wound that was throbbing to rhythms I had been living with for too long, and then at the kitchen sink washing up some dishes, I thought, “I’ll write to Claire!” and I knew I had the entry point to beginning to approach what appears to be a sea change, possibly a seismic shift of some sort, the details of which leave me sometimes angry, at other times sad, sometimes with a fierce joy and sometimes filled with despair. Let me confess, Claire, to feeling the fierce desire for vengeance and revenge — but at this advanced age, I know “better,” know that violence often breeds more violence. I did go back to Fanon, though, pulling down “The Wretched of the Earth” from my bookcase and turning to the pages marked by old Post it notes and with markings in the margins: “At the level of individuals,” he writes, “violence is a cleansing force.” But later in the same work — “Racialism and hatred and resentment — ‘a legitimate desire for revenge’ — cannot sustain a war of liberation.” Is this a war of liberation? America is still a colonial power grafted onto empire. I don’t know what the outcome will be — don’t think anyone does, but we are on a knife’s edge of possibility — isn’t that what poetry opens up sometimes? — and what I’m trying to do is what we humans always do — try to make meaning of phenomena around us. Having been schooled in the ways of the West and its intellectual traditions, I incline to making meaning in the way the West has taught us to value — “I think therefore I am” — but I know there to be other ways of being, of making meaning: the oral — “Mi say mi cyant believe it” — the tonal implications say so much more than the translation — I can’t believe it; the physical — through our dance and gesture; the musical — Sweet Honey singing Ella’s Song: “Those who believe in freedom cannot rest,” as I did this weekend past with four other Black, African-descended women, after placing on an altar objects connecting us to ancestors. This, of course, is all about spirit, which our ancestors brought with us, which sometimes is housed in organized religion and as often not. Spirit is what the enslaved African brought with him and her and which, even as it was being made forbidden, demonic, sustained them. We have lost many of those ways, haven’t we, Claire?

I know you know all that is happening, but I still feel the need to share with you, and I know I’ve taken a long time to get to the reason I’m writing to you. As of May 25th, we had been in lockdown, shutdown or sheltering in place or not in place — take your pick — for some ten to twelve weeks when a forty-eight-year-old African American man, George Floyd was murdered — lynched in broad daylight, pardon the cliché. George Floyd, I say his name again, an ordinary man who for eight minutes and forty-six seconds pleaded for his life, said he couldn’t breathe, and called on his dead mother for help while another man, a white police officer in Minneapolis, whose purported role is to serve and protect, knelt on his neck and extinguished his life. How to describe the look in the eyes of that officer — he looks around, clearly looking at someone, possibly the young woman recording his actions, his eyes not exactly blank but revealing no fear, no rage — it’s as if he were merely taking a piss, so normal it is to snuff out the life of a Black man, woman, or child — “Mi say mi cyant believe it,” and yet I do, because it has been happening for so long, for close to five hundred years, if we’re only thinking of the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans and their consequent dehumanization. In excess of that if we factor in the Arab trade in Africans.

Backed by the heft and weight of the white supremacist Euro-American state that has only seen the use value of Black bodies and consider African-descended peoples consumable and eminently dispensable, that white police officer, whom I will not name (you know his name in any event), because he stands in for all those people who consider Black life worthless, brought the weight of his body and the assuredness of his own superiority and supremacy to bear on George Floyd’s neck. “I can’t breathe” were his last words, echoing the same words Eric Garner used as he was being killed by police in New York on December 30, 2017. Time, like a spinning top, stood still — for a moment — then wobbled, Claire. Five hundred years — a blip in the age of the universe, the earth and even humankind, but it has been five hundred years of hell for us, ever since those goddamned Portuguese navigated around the southern tip of Africa, and ever since Las Casas decided that it was a good idea to bring enslaved Africans to the Americas to relieve the toll Spanish depredations were having on the Indigenous peoples of Central and South America. The rest, as they say, is history. And here we are at another cataclysmic spasm of outrage, anger and calls for white society to listen, not only to live up to what these so-called democracies promise, but to stop murdering us.

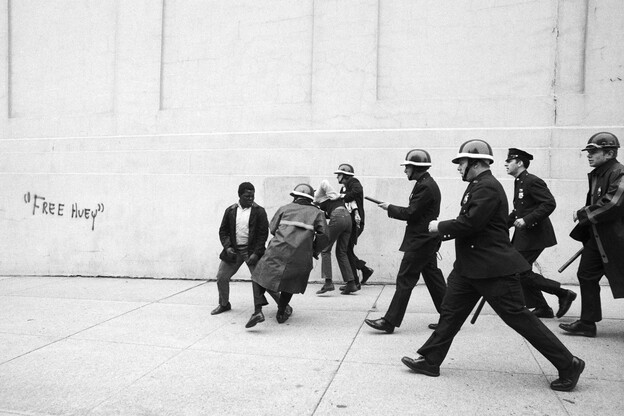

Because we now live in a digitally connected world, the murder — rather, the lynching, had been recorded by a young African American woman and, having gone viral, has upended the world and all the socially distancing protocols related to COVID-19. As you know only too well, Claire, this has only been the latest in a long, long history of racial violence against Black and African peoples, but this murder appears to be the spark that has ignited a worldwide conflagration of responses leading to marches around the world against anti-Black racism — “Mi say me cyant believe it.” This is a good time to explain my earlier Groundhog Day reference. Just before sitting down to type up this letter to you, I looked up a poem I had written some forty years ago — and decided I would put it up on Facebook. Forty years ago I wrote “Blackman Dead” in response to the murder of Albert Johnson by the police on August 26, 2017. Because he suffered from mental illness, he was “known to the police,” who went to his home in response to a call where he was shot. In response to demands by the Black community in Toronto, two of the three officers were charged. They were both acquitted. Since then there have been too many dead, Claire, and here I am posting this forty-year-old poem after I’ve been posting other more recent poems in the last few weeks, of my own and by others, on the continuing killing of Black and African-descended men and women — on how cheaply our lives are held. It was an odd feeling of having done this so many times before, yet it was still “new” — akin to, I’ve never done this before, I’ve always been doing this.

And In 1984, in Calgary, you would write the poem “Policeman Cleared in Jaywalking Case” about a fifteen-year-old Black girl who had been arrested, strip-searched, and imprisoned because she had not cooperated during the first five minutes of being stopped, had not provided identification with a photo on it and failed to give the officer her date of birth — “Mi say mi cyant believe it.”

Why did I begin with Mikey Smith’s words? Because it’s in the Caribbean vernacular, the demotic; in nation language, as Kamau Brathwaite, beloved griot who just passed, puts it. Don’t think you would have seen him yet — takes a while for the soul to transition — but you will. He knows we miss his presence deeply, but do give him my regards. I know you and I started out with different views on the vernacular, but for me that’s where the soul of our Caribbean people live — “Mi say me cyant believe it.” Brathwaite described Mikey as “an intransigent sound poet … not concerned with the written script at all.” Mikey himself saw poetry as a “vehicle of giving hope. As a means of building awareness … Poetry is part of the liberation of the people … I just want them fi understand what I deal with: describe the condition which them live in but to also say, Boy, don’t submerge yourself under the pressure.” On August 17, 1983, some men attacked Mikey striking him on the head with a stone as a result of which he died. He had attended a political meeting in the Stony Hill area in Kingston, Jamaica, the day before where, according to an article by the poet and professor, Mervyn Morris, he had “heckled a Jamaican Labour Party cabinet minister.” I’m sure you recall the intense political struggles in Jamaica around that time. In the same article Morris appears to go out of his way to assure his readers that “in spite of some of the original public responses, there seems to be no evidence that Mikey was killed because he wrote poetry, or because of the poetry he wrote.” Of course the fact that there appears to be no evidence doesn’t mean that the evidence doesn’t or didn’t exist.

I think a part of me wants to believe that poetry can drive men and women to murder — to do terrible things. My mind turns to poets like Lorca, Linton Kwesi Johnson (LKJ), Benjamin Zephaniah, Nikki Giovanni, Anna Akhmaotva, Okot p’Bitek, Ngugi, and Stella Nyanzi who was jailed because she wrote vulgar poetry about the Ugandan president, Yoweri Museveni’s, mother’s vagina as a form of political protest — poets writing on the knife edge of possibility, on the knee edge of life and death. A friend recently emailed me: “I read your FB poem and I find myself somewhat heartened, reminded that the words, poetry, can *do* something. Language activates the consciousness. My consciousness at least. The numbness, the catatonic despair lifted just enough for me to crawl out a bit further from under it … (s)o know that your words are doing work in the world, too.” I, too, was heartened by what she said. I think that is what we all hope for — that this gift that we nurture and craft over our lives, that often bedevils us, can sometimes be used in the service of — again the knife edge because words can be used in the service of evil, of wrong actions. But that’s always the risk, isn’t it?

Before closing I must tell you of one mi-say-mi-cyant-believe-it moment that I think you will relish, as I have, both of us being from the former colony of Trinidad and Tobago: yesterday, June 7th, 2020, in Bristol, England, a crowd of demonstrators attached ropes to the statue of seventeenth-century slave trader Edward Colston and pulled it down. They then dumped it into the River Avon. I’ve seen the statue with the coy explanatory note and done the “slave walk” — don’t recall if it’s called that — around the city. My response — about time! “Mi say mi cyant believe it.”

Best,

NourbeSe

ps: To be continued.

Claire Harris was a close friend. She was a powerful poet and thinker, her work being a finalist for the Governor General’s Award for poetry. She was also a beloved primary school teacher with the Catholic Board of Education in Calgary, Alberta. She passed away February 5, 2018.

Excerpt from “Policeman Cleared in Jaywalking Case”

Covidian catastrophes: deep, dark places of light