Creeley on Blackburn

From Jacket #12 (July 2000)

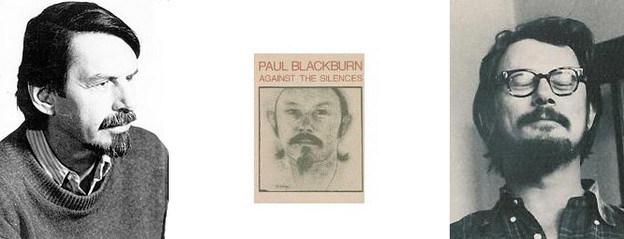

Editors’ note: Preface to Against the Silences, by Paul Blackburn, published by The Permanent Press, London and New York, 1981. Reprinted with permission from The Collected Essays of Robert Creeley, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1989. — Jacket2

I’D LIKE TO SPEAK personally of this extraordinary poet, and take that license insofar as these poems are personal, often bitterly so. I wonder if any of us have escaped the painful, self-pitying and meager defenses of person so many of them invoke. What we had hoped might be, even in inept manner worked to accomplish, has come to nothing — and whose fault is that, we ask. Certainly not mine? Having known both of these dear people, and myself, I have to feel that there will never be a human answer, never one human enough.

When Paul Blackburn died in the fall of 1971, all of his company, young and old, felt a sickening, an impact of blank, gray loss. I don’t know what we hoped for, because the cancer which killed him was already irreversibly evident — and he knew it far more literally than we. But his life had finally come to a heartfelt peace, a wife and son so dear to him, that his death seemed so bitterly ironic.

Recalling now, it seems we must have first written to one another in the late forties, at the suggestion of Ezra Pound, then in St. Elizabeth’s Hospital. We shared the same hopes for poetry, the same angers at what we considered its slack misuses. Paul was without question a far more accomplished craftsman than I and one day, hopefully, the evidence of his careful readings of the poems I sent him then will be common information. We finally met at his place in New York in the late spring of 1951, just prior to my moving with my family to France. He was the first poet of my generation and commitment I was to know, and we talked non-stop, literally. for two and a half days. I remember his showing me his edition of Yeats’ Collected Poems with his extraordinary marginal notes, tracking rhythms, patterns of sounds, in short the whole tonal construct of the writing. He had respect then for Auden, which I did not particularly share, just that he could use him also as an information of this same intensive concern. He was already well into his study of Provençal poetry, which he’d begun as a student in Wisconsin, following Pound’s direction and, equally, his insistence that we were responsible for our own education.

As it happened, we shared some roots in New England, Paul having lived there for a time with his mother’s relatives when young. But the Puritanism he had to suffer was far harsher than what I had known. For example, his grandmother seems to have been classically repressed (her husband, a railroad man, was away from home for long periods) and sublimated her tensions by repeated whippings of Paul. He told me of one such time, when he’d been sent to the store with the money put in his mitten, on returning he’d stopped out front and the change, a nickel, somehow slipped out into a snowdrift. And as he scrabbled with bare hands trying to find it, he realized his grandmother was watching him from behind the curtains in the front room — then beat him when he came in. Those bleak Vermont winters and world are rarely present directly in his poems, but the feelings often are, particularly in his imagination of the South and the generous permission of an unabashed sensuality.

At one point during his childhood, a new relationship of his mother’s took him out of all the gray bleakness to a veritable tropic isle off the coast of the Carolinas. I know that his mother, the poet Frances Frost, meant a great deal to him — and that her own painful vulnerabilities, the alcoholism, the obvious insecurities of bohemian existence in the Greenwich Village of her time, pervade the experience of his own sense of himself. His sister’s resolution was to become a nun.

Paul’s first marriage was finally a sad shock to me, just that I could never accept the fact of the person to whom he’d committed himself. She is the “lady he had known for years” in “The Decisions,” and one hopes she did find the “new life” that cost him so much. The antagonisms felt by her and my own wife provoked an awful physical battle between Paul and me one night, when we were all living in Mallorca (he was about to spend a year in Toulouse on a Fulbright), and for some years thereafter we didn’t see each other, although we had wit enough, thankfully, to keep the faith sufficient to let me publish Paul’s first book of poems, The Dissolving Fabric (1955).

During the sixties I was able to see Paul quite frequently, although he lived in New York and I was usually a very long way away. He and his wife, Sara, were good friends to us, providing refuge for our daughter Kirsten on her passages through the big city, and much else. Sara, characteristically, was able to get publication for another close friend’s writing (Fielding Dawson, An Emotional Memoir of Franz Kline, Pantheon, 1967), thanks to her job with its publisher. Elsewise Paul certainly did drink, did smoke those Gauloises and Picayunes, did work at exhausting editing and proofing jabs for Funk & Wagnalls, etc., etc. It’s a very real life.

The honor, then, is that one live it. And tell the old-time truth. Of course there will be human sides to it, but Paul would never argue that one wins. To make such paradoxic human music of despair is what makes us human to begin with. Or so one would hope.

*

Click here for the full article as it appeared in Jacket #12.