Coolitude poetics interview with Sudesh Mishra

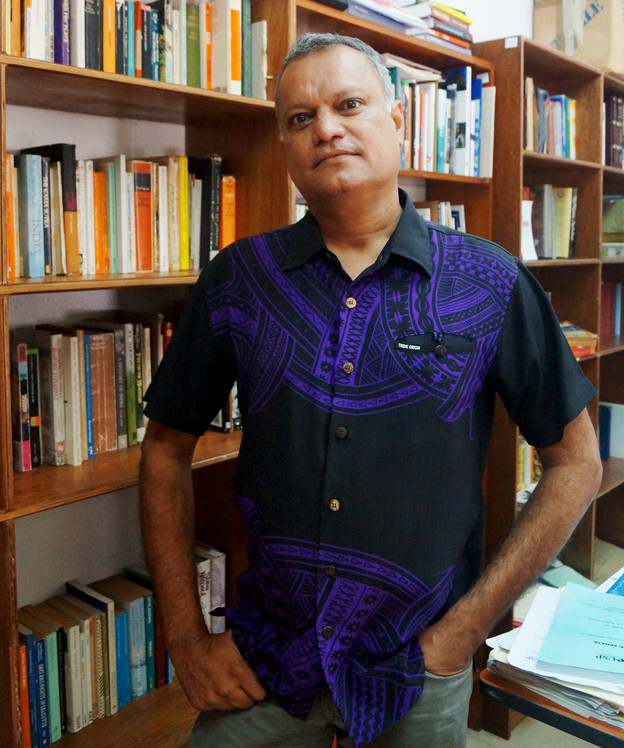

Sudesh Mishra is the author of five books of poetry, including Tandava (Meanjin Press), Diaspora and the Difficult Art of Dying (Otago University Press), and The Lives of Coat Hangers (Otago University Press); two critical monographs, Preparing Faces: Modernism and Indian Poetry in English (Flinders University) and Diaspora Criticism (Edinburgh University Press); two plays, Ferringhi and The International Dateline (Institute of Pacific Studies, Suva); and several short stories. Mishra’s creative work has appeared in a wide array of publications, including Nuanua: Pacific Writing in English since 1980, The Indigo Book of Modern Australian Sonnets, Over There: Poems from Singapore, and Australia, Sixty Indian Poets, The Bloodaxe Book of Contemporary Indian Poetry, Concert of Voices: An Anthology of World Writing in English, Out of Bounds: British Black and Asian Poets, The Turnrow Anthology of Contemporary Australian Poetry, The World Record, Contemporary Asian Australian Poets, and Contemporary Australian Poetry. Sudesh teaches at the University of the South Pacific in Fiji.

Rajiv Mohabir: Thank you so much for agreeing to do this mini interview with me! Your poetry, global in perspective, carries with it Indian indenture history. You write in form and against it. Characters like Aaji, Sati, and Hanuman appear in this, your most recent volume. Which poets and thinkers have been your biggest influences?

Sudesh Mishra: I was brought up on folk versions of The Ramayana and The Mahabharata. In fact, as a young man, my grandmother ensured that I was given significant roles in the annual Ramlila festival, which was held at a local school which also housed a mandir dedicated to Shiva. I have written about this festival in a fictional essay entitled "Lila." These two texts were formative for me as an adolescent. Afterwards, when in high school and at university, I learned to enjoy Shakespeare, Donne, Marvell, Pope, Yeats, Eliot, Frost, Auden, Rilke, Garcia Lorca, Neruda, Montale, Cummings, Beckett, Borges, Walcott, Naipaul, Garcia Marquez, Herbert, and Heaney. My doctoral dissertation was on modernism and postindependence Indian Poetry composed in English. I interviewed several of these poets as part of my field trip to India. I distinctly remember the interview I did with Arun Kolatkar at the Wayside Inn in Bombay. I learned from him that gravity and levity were not incompatible elements. I try and write about serious matters with a touch of lightness and about light matters with a touch of seriousness. In the context of Oceania, Epeli Hau’ofa’s reflections on islands have shaped my thinking. More generally, however, I have tried to swallow the world and gravitate towards whatever pricks my attention. It may be a startling remark from a philosopher or it may be the memory of my father fixing a door. I am as likely to write a poem about a gecko eyeing a moth over a scene of Christ’s last supper as about the dog that accompanied Yudhishthira on his final journey over the Himalayas.

Rajiv Mohabir: What are some concerns that poetry is able to handle with grace that, say, prose is not able to articulate, given the complex history of the Pacific broadly and Fiji specifically?

Sudesh Mishra: Poetry is simply the place where language mutinies against its own condition of exhaustion. The form of this mutiny can be lyrical, dramatic, or satirical, etc. If we compared language to a cellular body, the function of poetry would be to bring forth new cells to replace the dying ones. Fiji has gone through many coups and with each coup you find that language becomes increasingly instrumentalized, exhausted, because it has to serve the purpose of political propaganda. The magical thing about poetry is that as an art form it is useless, as Auden once said, but it is this very uselessness that permits it to resist the instrumental and functional aspects of language, to resist ideology in general. Poetry opposes every form of instrumental persuasion and is infinitely open to the generation of disturbing permutations in language. Simply put, it never gives in (to manipulative reason, to the injunctions of the ego or the state) and that, if you think about it, is potentially everything. It ends up saying more precisely by saying less. In this sense, it shares a kinship with dreams and music. I have become increasingly interested in poetry that sides with nonhuman objects and beings as I feel we have forgotten, in our infinite hubris, that we are no more or no less privileged than other animals and things. I believe that we need to radically redefine the way we relate to our planet.

Rajiv Mohabir: In fact, your poem, “Diaspora and the Difficult Art of Dying,” seems to be in conversation with David Dabydeen’s poem “Coolie Odyssey” in that there is travel to various national spaces and a first-person speaker who navigates these terrains. What are some other intertextual poems that you see your work harmonizing and colliding with?

Sudesh Mishra: I really liked David’s first book, Slave Song. It’s an extraordinary volume because it introduces a subaltern voice that you don’t get to hear very often in poetry. I think the Caribbean poets, including Walcott and Brathwaite, gave to English a new dynamism by harvesting the genius of creole, patois, and the genre of the calypso. These poets didn’t really set out to be avant-garde. Caribbean English, with its lilting cadences, its syntactical innovations and elisions, is fundamentally an avant-garde language, and poetic form bends with it. "The Spoiler’s Return" is a poem I admire greatly for this reason. The form of the classical satire in rhyming couplets has to adjust to the new music of creole and patois. The result is caustically spellbinding. Coolie laborers, as you know, were dispersed to many colonial outposts, including Africa, Oceania, and the Caribbean. So David and I share that history which, incidentally, is an unfinished one in that the dynamic of dislocation — political, economic, or psychological — has not ceased for many of us. Death, for me, is a condition of homely quiescence, of being finally at one with some part of this planet. This condition often eludes the dislocated subject. Our particular hell consists of assuming multiple avatars as a consequence of social rejection and continuous migration. "Diaspora and the Difficult Art of Dying" is about a coolie subject who cannot die because the nightmare of history haunts the time of his present. It’s a condition he shares with the Sybil of Cumae.

Rajiv Mohabir: If you could describe your sense of poetics in five words, five books, and five songs, what would those be?

Sudesh Mishra: I’d rather approach the question differently. I write in a language that knows no borders, no national boundaries. It is a language that assimilates the particular everywhere and yet remains general in its appeal and distribution. I have never thought of my work as being defined by some national paradigm. English is a wandering cur that has completely forgotten its origin and territory. It knows only detours and urinates in any street, in any city, in any country.

Rajiv Mohabir: One of the most memorable things that has ever happened to me was when you came to Honolulu. I asked you if you knew any Bhojpuri and you began singing a Bhojpuri folksong across the table. I believe it was the song that you translated found in Vijay Mishra’s The Literature of the Indian Diaspora: Theorizing the Diasporic Imaginary. Have these kinds of songs been influential in your sense of form and poetry?

Sudesh Mishra: It was a bidesia that I sang and, yes, Vijay used it in his excellent study; it belongs to the tradition of North Indian viraha songs, that is, songs of longing-in-separation, which probably has its origins in Jayadeva’s long poem, Gitagovinda, composed in the twelfth century, which deals with Radha’s unbearable longing for an inconstant Krishna. Bidesias were sung by coolie women during the indenture period and dealt primarily with their sense of dislocation from their villages in India. So, like the blues in the United States, the bidesia became politically charged in the plantation context of Fiji. Longing, I suppose, as a form of political protest. They are beautiful, moving, wistful songs, and I would like to think that they inform my sense of poetry as well as history. In terms of drawing directly on Indian poetic forms, I have written a handful of vacanas (or bhakti poems) in English, drawing largely on A. K. Ramanujan’s extraordinary work in this area, but these are not yet published.

Rajiv Mohabir: Can you tell me a little about what you are working on now?

Sudesh Mishra: My second collection, Tandava, contained a poem called "The Loving Song of R.J. Tangaya" — a parodic homage to Eliot. Tangaya is a wise fool (tangaya: suspended) and I was able to escape from my personality (since I am neither wise nor a complete fool) by stepping into his character. Tangaya lay dormant for a number of years, but recently resurfaced in The Lives of Coat Hangers. Now he won’t let me be and has practically moved into my house and assumed my place and from this place is writing poems encapsulating his view of the world. I have turned into his amanuensis and he’ll probably direct me to dispatch his poems to a publisher when the manuscript is ready. For all I know, he might even try and compose a bidesia.

Coolitude: Poetics of the Indian Labor Diaspora