Coolitude poetics of Andil Gosine

A Coolitude interview

Andil Gosine (PhD, MPhil, BES) is an associate professor in Art and Politics at the Faculty of Environmental Studies, York University. His research, writing, and arts practices explore imbrications of ecology, desire, and power. He has published numerous scholarly articles in anthologies and journals, and his work has been exhibited internationally. In 2018, two solo exhibitons of Dr. Gosine’s work will be staged in Canada, “All the flowers” and “Coolie, Coolie Viens.” Accompanying the latter will be a comprehensive catalogue with essays about his work by various writers and scholars. A complete listing of his publications and exhibitions is available at www.andilgosine.com.

Rajiv Mohabir: First of all, thank you so much for taking time to answer these questions! I am so happy to have your voice in this project. How did you first hear about Khal Torabully’s work?

Andil Gosine: Having lived off and on in Paris over a span of fifteen years, I only ever encountered one other Trinidadian — and only in the fifteenth year. I had made close Haitian friends that, looking back, constituted a kind of Caribbean community for me, but one day a date took me to a Mauritian restaurant and I was really very struck by how much their version of red kidney beans looked like and tasted like my mother’s. The space of the restaurant, too, seemed very familiar and familial, and I think the surprise of this resonance stirred my interest in finding out more about Mauritius. That night I went online and Torabully’s Coolitude was the first thing that came up. I never saw the date again, but Torabully’s work became an important part of my life.

Rajiv Mohabir: How has Coolitude as a concept for understanding South Asian labor diaspora impacted you and your work? Specifically, what are the questions of Coolitude that you address in your art or are haunted by?

Andil Gosine: The two primary elements of Coolitude — its notion of reinvented and dynamic culture and the necessity of grieving — underpin and inform my work. The former was always there and strengthened by Torabully’s poetic renderings of indentures’ processing of and creative response to brutality. His insistence that we contend with the violence and mourn the impact of the labour system, right to the present, stood out from other studies of indentureship. His call to recognize historical pain, and to grieve, felt so critical and underattended. The tenor of his work was deeply resonant with my understanding of the intergenerational consequences of indentureship and other structures of colonialism.

I am very committed to an analytical framework that recognizes the imbrications of the personal with the social — we can never stand apart from nor are we entirely products of our history — and I felt that Torabully’s passion and personality offered a more complex notion of the indentured subject that was more compatible with my work. In a lot of the writing on indentureship and post-indentureship, there is a tendency to talk about collective experiences — whether of all indentures, or, say, of “indentured women” — sometimes at the risk of diminishing the complex subjectivity of the person. We need to hear and parse through the details of more stories. We haven’t nearly begun to do this kind of work.

Rajiv Mohabir: Your art-performance series “Wardrobes” includes four metal and textile objects — the Cutlass, Orhni, Scrubs, and Rum and Roti — which explore “how traumatic historical acts shape the most tender parts of our intimate lives, and more specifically, trace inheritances of indentureship — the system that brought Indians to the Caribbean as replacement slave labour to work sugarcane plantations” (ARC). My first question is how has our coolie history impacted us? Next, why are these objects specifically emblematic of the Indian indenture diaspora?

Andil Gosine: There are four objects in the collection: a white gold Cutlass, a Rum and Roti bag, a set of doctor’s Scrubs, and an Ohrni veil. Each of them foregrounds ambivalence: the objects convey the notion of simultaneous pleasure and violence.

In the performance for Cutlass, for instance, I recall my conflicted response to the object: it’s this wonderful memory of my grandmother cutting sugarcane for me, in these delicate little pieces, but it’s also sheer terror of the instrument’s violence: all the stories of it being used by Indians to slash other Indians, particularly in cases of domestic violence.

This simultaneity of looking back with pleasure and horror is, I think, the legacy of indentureship. Our production as coolies — both our ancestors who worked the fields, and those of us who would still be called coolies generations after their labour contracts ended — is laced with violences and also generative of pleasures. Often, we can even become very desiring of things that destroy us, as with Rum and Roti. Here, again, are two things which are deeply desired, and also incredibly destructive, through diabetes, obesity, and also violence.

I should add that I am not setting up a dichotomy of “good” pleasure and “bad” violence here, but rather calling attention to the contradictory and evolving tensions that colonialism’s architecture, which included indentureship, produced. This conflicted history also does not make the coolie special — it underlines our complex humanity.

Rajiv Mohabir: Who are your artistic heroes? How do you trace your artistic lineage and genealogy?

Andil Gosine: I am not sure how to trace my “artistic lineage” as my arts practice is young and not particularly intentional. I turn concepts into objects and experiences when they emerge; Wardrobes emerged from heartbreak, for example. My practice has been enormously influenced by my work with the feminist artist Lorraine O’Grady, and also by my friendships with artists Leor Grady, Sur Rodney (Sur), and Richard Fung. Visual art has been an historically underutilized form in the Indo-Caribbean community, with notable exceptions like Shastri Maharaj and the incredibly complex Wendy Nanan, among others.

I am excited by the burst of contemporary work by younger artists like Kelly Sinnapah Mary, from Guadeloupe. Kelly and I collaborated on a graphic novel that draws on our coolie heritage in interrogating “grey space between sexual awakening and sexual abuse.” I think we’re engaging in uneasy but necessary conversations.

The visual aesthetics of the village where I grew up are stunning, and so productive; they are endlessly borrowed by others from outside those communities. My artistic lineage passes from my grandmothers and they way they organized objects in the household, Hindu pujas at my home and at the temple I attended Sunday mornings, and of course the natural environment of canefields and forests, animal sounds that warmed and terrified.

Of all artists, the one that sustained, inspired, and shaped me most is Sinead O’Connor. Her penchant for truthful vulnerability, for expressing the fullness of the human experience, is art at the peak of its possibilities.

Rajiv Mohabir: Your performance of “Our Holy Waters, And Mine” I find particularly moving in that it locates the individual in a state of constant movement/migration. You have glass jars, each etched with the phrase “Kala Pani” and a specific body of water that you are “from” or have lived by. Meanwhile there is a voice that proclaims “The Ganges are not Our Holy Waters.” What are the nuances you convey about migration and Indo-Caribbean heritage and identity in this piece and how did this project evolve from your intention?

Andil Gosine: I did not grow up in a family or community with an explicit, strong reverence for India. In recent years however — as India itself became an economic superpower — there seemed to emerge a fascination with Indianness that is premised on an authentic version of it existing in the subcontinent, one that keeps others in the diaspora beholden to it. I have been struck by two kinds of comments in particular: Indo-Caribbean people boasting of having access to “real” Indians, “real” Indian objects and Indianness itself, and the really bizarrely common claim by some of them that their ancestors were “not indentures.”

I understand the false investments in blood lineage cut across all peoples, but one of the things I love about the history of indentures and their descendants is how powerfully they contested essentialist notions of identity, particularly of caste and gender. The rejection of the Ganges as “Holy Waters” is a rejection of a fixed or stable identity with a discoverable root. The loss of identity that crossing the Kala Pani (the dark waters that indentures crossed from India to the colonies) is supposed to represent are “Our Holy Waters,” I argue. Many indentures were seeking liberation from India’s own oppressive systems of social organization, including caste and patriarchy, and I want to celebrate the liberatory aspiration, even if it wasn’t achieved.

I am truly heartbroken to hear some Indo-Caribbean people revise our histories to evacuate indentureship, as if there is anything shameful about survival. An Indo-Guyanese friend last year confessed to me that he grew up feeling “proud” by his family’s claim that they were not indentures. Another insisted on the definitive Brahamanic roots of her family. I am not surprised, but I am truly heartbroken that these racist — and ultimately, incredibly stupid — investments in hierarchies of blood and body persist among the people they are intended to punish.

The first six jars in “Our Holy Waters, And Mine” are labelled with the names of the waters that indentures crossed, but the next six are the names of the waterways in the cities in which I have lived. The “and Mine” in the title is an explanation of why “La Seine” become Kala Pani, for instance. As in all of my work, I want to underline the imbrications of the personal with the social, without surrendering one to the other. There are waters that are ours, but there are also ones that are just particular to my story.

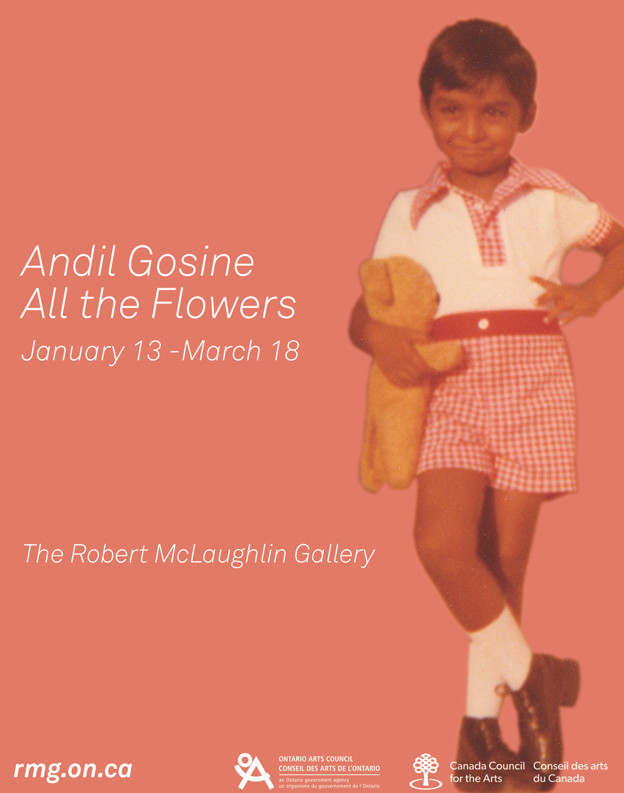

Rajiv Mohabir: Can you tell us a little about the concepts underpinning your next solo exhibition “All the flowers”?

Andil Gosine: I love flowers; I have always loved flowers. This show is a partial “autobiography in flowers,” from my childhood in Trinidad, when I was often the kid responsible for picking flowers for offerings in Hindu rituals, or making flower garlands, through to my family’s move to Canada, in a winter environment devoid of flowers, to the present, including a kind of floral resurrection that grew from living by the flower markets of France. One of the pieces, for instance, recreates the Ixora — a flower that is as commonplace as grass in Trinidad but is actually not indigenous to the Caribbean.

The Ixora came with the indentures. They are such beautiful flowers, and their form materializes that conceptual obsession I have of the personal and the social, as they always flower in little groups, never alone, but also each little flower is its own. I went to Trinidad as part of my research for this work, and I had such a moving and wonderful experience finding these flowers, making garlands from them, and photographing them.

I should add that this show, like all of the others, is more generally about the human condition and broaches themes such as love, isolation, and belonging. Because I cite materials that are part of my history, that fact often gets reduced to a Caribbean artefact in an anthropological sense, but I am interrogating our human impulses, our desires and fears, our kindness and cruelty.

Coolitude: Poetics of the Indian Labor Diaspora