Brodsky, reconstituted

There is a peculiar phenomenon at work in contemporary Moscow, notes Mikhail Iampolski in his 2018 book Park of Culture: Culture and Violence in Today's Moscow: a discomfiting correlation — or perhaps more precisely, a consent, a complicity — between the rise of arts and style culture in Moscow (which, when not funded directly by the Moscow Department of Culture, is often in some way enabled by it) and a parallel rise both in state repression and the cultural authority of the Orthodox Church. In recent years, downtown Moscow has embraced the manifold cultural products that constitute a “life-style,” as the multitude of microbreweries, new local fashion designers, boutique restaurants, edgy theater performances, mixed-media festivals, the normalizing of Soundcloud rapper “street-fashion” attest. (Left: Noviy Arbat, not far from Dom Tsvetaeva.)

There is a peculiar phenomenon at work in contemporary Moscow, notes Mikhail Iampolski in his 2018 book Park of Culture: Culture and Violence in Today's Moscow: a discomfiting correlation — or perhaps more precisely, a consent, a complicity — between the rise of arts and style culture in Moscow (which, when not funded directly by the Moscow Department of Culture, is often in some way enabled by it) and a parallel rise both in state repression and the cultural authority of the Orthodox Church. In recent years, downtown Moscow has embraced the manifold cultural products that constitute a “life-style,” as the multitude of microbreweries, new local fashion designers, boutique restaurants, edgy theater performances, mixed-media festivals, the normalizing of Soundcloud rapper “street-fashion” attest. (Left: Noviy Arbat, not far from Dom Tsvetaeva.)

But the simultaneity of these three realities — the shadow of an often Soviet-nostalgic State, the omnipresence of the Church, and a novel and various license that projects a sense of freedom — do not seem to produce any lasting dissonance, any real discord that might midwife new and generative cultural energies. All three realities instead collapse into an eerie synthesis: a synthesis that itself abets the ahistorical political stasis (Stabil’nost!) of Putinism, enriching its theatrical repertoire of self-obfuscation with a series of dazzling costume changes. Thus a prominent aesthetic in Moscow culture — a cultural mood visible in performance, in fashion, in music, in daily life — that oscillates between stylized despair and unreflective nostalgia, between cynicism and sentimentality. It is an aesthetic system that is, like Putin’s governance, prone to the affective.[1] But if contemporary poetry does not always challenge this order, I thought, it remains largely outside its influence: because too ambiguous, too “slow,” too interior, too marginal — and because in poetry, in Russia as everywhere, there is no money to be made.

Fast-forward, then, to a performance of Joseph Brodsky’s poems held at the Gogol Center last Friday, in celebration of the poet’s birthday. I had purchased the ticket cautiously, a caution born of several factors: first, the performance was part of a larger festival that promised to prove contemporary Russian poetry neither irrelevant nor dying; a conviction I of course support, but the promise had been delivered with hints of bombast and a design scheme reminiscent of late Fall Out Boy. Then the often uncritical and sometimes hagiographic reverence towards Brodsky in Russia, which, taken in concert with the premise of the performance — his best-known verse delivered by actors from a variety of well-known Moscow theaters, with unspecified musical accompaniment — invited further vigilance. Lastly, I had a certain wariness towards the venue itself, having seen Serebrennikov’s Machine Muller there — a performance which felt at best ethically sterile, at worst, cruel: а parody of the human fragility and complexity disclosed in Pina Bausch’s compositions.

The Gogol Center — its main hall a complex of Instagram staging areas, each with its own #gogolcenter placard — was, as customary, abuzz; a long line for entry, and the performance hall, reconstructed in stark notes, but with chandeliers, was packed. The stage was black, bare but for a treated upright piano and several laptops rigged to various synth controllers. White floodlights illumined the stage’s lone mic and the swirling produce of a smoke machine, obviously already vigorously in use. The festival’s director stepped forward to deliver, by way of evening’s introduction, his own interpretation of his “favorite Brodsky poem” — and we were off.

A performance of Brodsky’s “Pesnya bez muziki (Song without music),” Gogol Center.

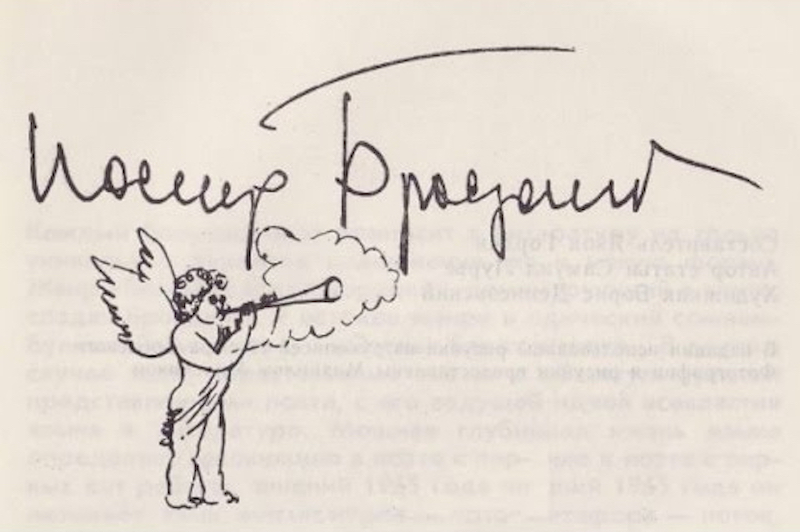

Brodsky’s idiosyncratic reading cadence is well-known: “that notorious shamanistic way of reading,” as Lev Losev put it — sing-song, chantlike, giving even his most latent-Romantic verse (as Dashevsky notes) a sense of ritualistic impartiality. One can hear in those recordings both ironic self-reproach and a lilting musicality of form. His cadence itself helps to redeem certain poems into a greater interpretive possibility. But the cavalcade of readers at the Gogol Center had, by inner accord or conscious design, agreed to collectively adhere to a single intonation — fraught, declamatory, histrionic — and to confine themselves almost exclusively to Brodsky’s love poems. This, along with the musical accompaniment, which ran from the Michael Nymanish to outright djembe and guitar, the smoke machine’s circulations, and the dramatic lighting, performed a substitution of content for affect somehow reminiscent of the holographic projection of Tupac Shakur at Coachella. Here too was the erasure of the substance of a person — of both work and life, and the interpretive and ethical demands that go along with them, the flesh and cost of thought and experience — and the replacement of that substance by mere sensorium. Gone from view was that which makes Brodsky difficult, meaningful, problematic, thinking — his irony, his metaphysics, the existential loneliness freighted with a comic-grotesque, the “trompe l’oeil of personhood” felt in his work, his Jewishness, his political conservatism, his fascination with the relationship between poet and tyrant, between language and empire, etc. (Photo below of a Brodsky drawing.)

A few days later, attending a choral concert in the lower chamber of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour — an immense hall in the scheme of an Orthodox casino, with prodigious mirrors, red velvet, brocade, a cafe, shops, and the burbling of Slavonic Muzak (!) — I had an uncanny sensation of its kinship to the Brodsky reading. Not, of course, in its substance: here, a public grade-school choir sang Orthodox religious music (“Holy Russia is Orthodox!” shouted one little girl, cheerily, ominously, as part of her solo) below a contemporary rendering, exploded to theme park proportions, of an icon of the disciples. No, the analog was in the tactics of the environment itself: the brocade and velvet, the sumptuous carpets had robbed the hall of any natural acoustics — but to recall the mythos of reality, the sound system was patched to “cathedral reverb,” supplemented with the occasional artificed bell. Just as the church simulated the sensorium of itself, evacuated of substance, so the Brodsky reading achieved an affective reconstitution of the poet’s work, removed from the grounds of its reality. I had the sense, looking for a restroom in the subterranean depths of the cathedral, that I might open a wrong door not onto the expected sink arrangement but onto the Gogol Center itself, to a holographic projection of Brodsky reading to a packed audience. That each event, each institution was somehow sutured to the other — and, in their unlikely synthesis, together formed a single creature, its antagonistic parts rendered seamless when apprehended as a whole.

Choir, Cathedral of Christ the Saviour.

Choir, Cathedral of Christ the Saviour.

1. The Putin regime’s preference for cultivating sensation over any singular ideological conviction — its essential ideologylessness — is something new to Russian experience. In the post-post-Soviet context, the use of “affective governance,” as part of a complex of different modes of power, has proved highly successful, perhaps in part because it both precedes and supplants the need for social consensus or historical reckoning, projecting instead the state’s continuity through a complex of sensation.

Twelve gates to the city: contemporary Moscow poetry