Rae Armantrout, 'The Way'

LISTEN TO THE SHOW

LISTEN TO THE SHOW

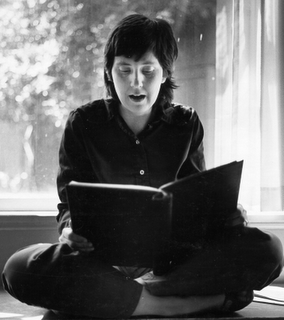

This time the PoemTalkers were Ron Silliman, Rachel Blau DuPlessis and Charles Bernstein, and our poem was Rae Armantrout’s “The Way.” Charles had already spoken with Rae about this poem briefly during their interview in the Close Listening series, so we went into our convo knowing that Rae sees the poem as having two compositional parts—a first part consisting of found phrases, items from the poet’s notebook of linguistic observations, a collage of voices, no fixed I. “I am here” is Jesus revealed to you in a pew, but I is also a poem’s prospective speaker: someone saying something tautological. Where else would you be, at the moment, than here? The second half, again according to the poet—revealingly or not—is a quasi-personal recollection: being read to as a child, getting lost in a story and thus feeling “abandoned” by the mother who gave her the gift of books. Gretel-like,  does she “come upon” these trees, this wood, each time diving into the wreck of each new now-nonnarrative venture? The most relevant of such ventures being...this poem itself? Who is lost in it? Have we lost the poem’s speaker, only to come upon her again (and again)?

does she “come upon” these trees, this wood, each time diving into the wreck of each new now-nonnarrative venture? The most relevant of such ventures being...this poem itself? Who is lost in it? Have we lost the poem’s speaker, only to come upon her again (and again)?

Charles chants lyrics from Grease: Grease is the way I am feeling. Rachel reminds us that “I am here” can also read as “Kilroy was here” does — a marker left by someone who came randomly before. Ron helps us focus on the ending: a grand vision expected, a definitive something, the light coming down through the trees, and what we get is…“again.” The sort of thing that keeps happening over and over. “Once” (as in “once upon a time”) in “once again” (the fairy tale’s synchronicity).

July 7, 2008

the new Eigner

Ron Silliman has written for his blog a terrific review of the big new multi-volume Collected Poems of Larry Eigner.