Why can't I touch it

On Chris Hosea's 'Double Zero'

Double Zero

Double Zero

“Don’t seek that all that comes about should come about as you wish, but wish that everything that comes about should come about just as it does, and then you’ll have a calm and happy life,” Epictetus advises in the epigraph to Chris Hosea’s second collection, Double Zero.[1] The Stoic maxim is fitting for a collagist like Hosea, whose poetry seeks to capture and present everything stripped of an artificer’s will; the speaker of “Little Salt Book,” for example, remarks that it is “[d]isappointing that books are written by persons” (37). These poems reject the model of surface and substratum, linear chains of logic, narrative, or meditation — poetry that conceals and ultimately bestows upon the diligent reader a kernel of meaning. Instead, Hosea’s poems are horizontally distributed linguistic planes, glittering splinters of the quotidian sliding through one another, shrapnel of heterogeneous temporalities. They conform to Rancière’s definition of the aesthetic regime under which much of contemporary art operates: in these works the sensible is “extricated from its ordinary connections and is inhabited by a heterogeneous power, the power of a form of thought that has become foreign to itself: a product identical with something not produced, knowledge transformed into non-knowledge, logos identical with pathos, the intention of the unintentional, etc.”[2] In espousing a Socratic know-nothingness and eschewing the polemical or confessional mode, Hosea’s poems achieve — despite their fervor and restlessness — a kind of Stoic calm, if not happiness. Yet the specter of intention, even the intention of the unintentional, haunts these poems and instills within them a compelling tension.

Nonknowledge, unintention, forms of thought foreign to themselves. These are familiar tropes in (post-)Language writing and (post)conceptualism, wherein the notion of a unified, stable subject/author in full command of the poem dropped in the reader’s trembling hands is laughable. In these poems that “speak nothing of yourself to you” (17), thought has indeed become foreign to itself; to do so it must have a double nature, and the pair of zeroes in Hosea’s book title connotes this evacuated self-become-text staring blankly at its alien foundation, or at the Humean perception-bundle of the other it has blown against.

Hosea indicates this alien foundation in the collection’s opening poem, “I Love You,” in which the speaker voices the desire to “push my head up your soul” (1). The speaker later recounts both how “you opened a hole in my lifetime” and “I opened a hole in my lifetime” (2), suggesting that the difference between you and I reduces to a pair of zeroes/holes (a later speaker gropes “to plug your butt I mean my own” [20]) in this precataclysmic instant in which we billions together desire a total destruction of names, which act is the only vigorous truth. The speaker’s thrusting head into our so(u)lar anus constitutes the first image of the double zero that casts its shadow over the collection: the zero of the animus foreclosed by the ravages of late capitalism (“I am a flesh bell went to market jingling” [13]), its vacuity penetrated by the second zero of the speaker’s head, a becoming-animal mechanically perpetrating “abstract thing violence” (1) in a society that in the last vestiges of neoliberal decorum can do little to conceal the heaving sea of porn on which it floats.

The eviscerated subject is refigured in the second poem, tellingly entitled “Player Zero,” in which the speaker observes, “today I get myself” (3). The “get” here implies that the I of the poem experiences selfhood as something bestowed (but how should we imagine the entity that awaits that bestowal?) — see also “face to face I am Chris for today” (53) and “I guess I want to / be myself, be someone new” (63). Or does “get” denote “understand,” “comprehend,” or some other shabby approximation implying doubleness and the (false?) psychoanalytic promise of insight into oneself? “Get” also suggests “beget,” and thus an asexual proliferation of subjectivities that “today” is helpless to isolate. No matter. All is dashed in the next line’s absence of subject pronoun in the infinitive, “to be gone now nothing hurting nothing.” The soul is not hidden beneath/behind the text, but is the told text itself — “you know about my soul I told you” (26).

In “This Is for You” we have the declaration “I am confident hardwood / paper leaves / such writ as Kant changed / the point is not to get the statement” (51). Is the speaker here identifying metaphorically as confident hardwood, bold and horny, or as a tree/text with paper leaves — the only material trace of him the page and the writing thereon, a Kantian critique that’s deemed our epistemological compensation for being exiled from the Ding an sich? Or is there an implied “that” after “confident” in the first line — does hardwood modify paper, which is both leaf and leaver of subjectivity’s trace, the I-think whose existence Kant could only assert as a necessary adjunct to the forms of intuition comprising the phenomenal manifold? Stop, the final line implores the interpreter. There is nothing to get, just a “portable sign” or “zero word” (39) — as Hosea fleetingly defines language elsewhere in the book — circulating between zeroes. That zero self becomes the refracting world-fragments in Hosea’s verse, a transition depicted in “Walking to Birmingham,” wherein the peripatetic speaker, the not-I “On the towpath to eternal life,” who “just can’t / genially gesture at assumed outlines” but must refashion and call them into motion, disperses into world by poem’s end:

it was the world and not me it was the world

that moved arrow fast blown turning its cold seam

it was the world surface slick diffusing starlight

and not me wrapped in warm perpetual fall

low great heavy cotton ball stone-colored clouds

it was the world it was the world it is there (19)

If the absent self were the only thing to see here, it’d be a tired story. As much as these poems sever the knowing head of authorial intention, the collage requires a will to extricate the fragment from its familiar connections and reconfigure it among other elements within the artwork. Even Epictetus, in the quote from the epigraph, recognized the impossibility of abolishing will — we are told to redirect our wishing, not to stop it altogether. With will comes desire, and these poems gather tension insofar as they wander from the serene Stoic Porch into the Epicurean Garden, exploring the glistening slug trails of eros. Plunged in and constituted by the secular babble of portable signs, the speaker of “Little Carbon Book” voices the urge to “be fixing a ground” and to “recall what I always knew / I want to eroticize time / Make something which lives / Articulate something” (39). This desire to fashion a living artifact from a grounded subjectivity constitutes a much more classical (think Pygmalion) image of the aesthetic act, even if the speaker who wants to articulate something also admits that “I don’t have much to speak of never did” (62). The admission also recalls Ashbery’s antipolemical statement that he doesn’t have anything to say.

Hosea’s speaker’s desire to “eroticize time” — what Lisa Robertson, who similarly explores “the erotic feeling of non-identity,” calls “the sex of remembering”[3] — is a major theme of this volume. For Hosea, sexual desire is bound up in the communal experience of art and the traditional injunction not to touch the work (“I just want to kiss your installation” [40]), an injunction that conjures memories of and further desire for sex. Thus, there is no framing in the traditional sense, no hallowed enshrinement; rather, the task is to “frame though it go from sight / above behind around afar / elements now slow or climates / fast” (23). These lines are burgeoning, fervid, catholic in their yearning. Hence, the Buzzcocks’ “Why Can’t I Touch It” — referenced in “Tape Hiss” (56) among myriad other pop, rock, and indie songs of the late twentieth century — serves as an apt anthem for the subjective strain against the limits of the socially sanctioned that characterizes much of this book. “[Y]ou can’t have it all,” the speaker of “Who Is the Big Winner” proclaims, “but you can have some / of everything, a fuck, a smoke, a random new / something” (5). But that’s not enough. “I want more,” the speaker continues, splitting open the trembling walls of the zero to envelop the object of desire and “work her tits so they spurt milk,” mingling two erotic temporalities: the encounter with the “grinning, tallish, gangly” aspiring artist at MoMA and the subsequent blind infant suckling at the maternal breast (5, 6).

The “work her tits” can be classed with a handful of other misogynist moments — “she chokes on me, doesn’t stop” (5); “I never did her” (7) — that, if one were treating the speaker as male and unified throughout the book, might be attributable to the influence of the “Henry Miller paperbacks” that the young speaker who leaves his home and his family in “Parted on the Side” brings to college with him in anticipation of the “doors / of sex” opening (9). But if these lines allude to Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Boxer,” the speaker’s awkward attempts to assert some (toxic) masculinity ultimately leave him like that song’s subject, cut and crying out in anger and pain. The poem is a rare instance of narrative — albeit punctuationless, fluid, and shifting — and recounts with poignant intimacy a desire for a fellow Johns Hopkins student in the early 1990s: “we were alone I freaked when she said / looked at my hands held my back firm / said nothing went back to my room.” The speaker’s machismo fades as he realizes “her time that time was hers / in time,” that other zero now who “saw through me” who “never moved to kiss her” (11, 12).

This episode, and other “bits of memories precious fictions losing definition” (12), constitute the atmosphere of remembered desire that permeates these poems; the atmosphere recalls New York, where Hosea has lived for well over a decade: “she whiffs of sweet / back Brooklyn someday afternoon” (5). Not that this book should be read autobiographically; as the speaker of “Tape Hiss” asserts, in a rare moment of extended meditation on the fictive self: “Always you could have chosen other moments, other seconds, other spaces, other sounds, other songs, other stations, other words, other friends, other lovers, other orders, other passive intentions. You missed out, you know it. You in fact just are this missing, sodden archive of unlogged roads traveled” (55).

However, despite the proscription “don’t fuck so close to me” (8), it is often we readers and not some remembered other that these speakers press against in their desire. “I Love You” is characteristic of this mode, as is “Same Time,” which ends with an act of fellatio that again mixes speaker and addressee as blower and blown, like the stem shadows near the performers who “brush blue fruit and come to and see stars arise” (46). The speaker has “said I love you / with a wound I can’t see,” and this primal hole/zero lends these words a hostility at times that is openly acknowledged: “the heat in my quiver probably part cruel fire” (62). For instance, the speaker in “The Final Countdown” (Europe) tells us to “imagine it is the two of us / fucking reader” (30), and the enjambment isolates the last two words on their own line, forcing the possibility that it is not the two of us fucking, but rather that it just the two of us, the speaker and we fucking readers, alone in a world where “[p]eople give pain” (37) and “everyone / is out to / get you mother fuck- / er” (48). But by and large these speakers don’t have pointy little hearts. “The Final Countdown” continues with “I slide under you and lick your asshole / because I love your asshole” (30), and the speaker’s compassion is evident: “inside the reader a beloved place / hurts the heart is sprained / and worse considered a mere machine” (29). The poem ends with the speaker and reader merging into “just humming energies” that in turn fuse with the erotic interplay of the world at large, “because there isn’t just one / of him or one of me or you / in this many universes / or one pussy one cock / so many millions” (30, 31).

Hosea’s polestar, insofar as the compendious desire that interfuses these poems is concerned, is Whitman. I admire the capaciousness of this sensibility, which locates the poisons both within the unstable self and in our contemporary situation, with its “colonies marked for pollution” (24), “sacked territories” (52), and “buildings exhaling the mind poisons,” where “life is artificial and kills all imagining” (60). These poems ricochet off trauma on both global and personal scales, and yet one senses an embrace of all of this, since “what turns me on right now / are things and people and places and people” (6). Like the speaker of Drum-Taps moving in and among the atrocities of madness/war, in “Know Your Name” the speaker has to duck the bloodspray of a Bellevue mental patient castrating himself with a salvaged safety razor and who is rolled on his hospital bed away from the speaker’s own:

just remember that bed

and think of the bed before that

and the one before that

and so remembering bed by bed

you can think of all the walls

all the horizons

all the women and men and children

who sheltered you

where you were

you are a child hardly before you forget

know your name

remember your name

your name is (60)

The poem ends on this piercing absence, this zero-name to be filled by the reader. Here thinking of prior beds and the nameless patients that inhabited them becomes an act of remembrance, an appeal to acknowledge the shelter and community needed to stave off madness.

The book’s finale, “So Many Fortresses,” is written in memory of Eric Garner and also moves in a Whitmanesque register while conjuring the horrors of an ostensibly postracial America. “The music / is not different, the only thing that is / different is the lyrics” (65), declares the speaker, and Hosea catalogues in repetitively modulated fragments how racism has only changed its manifestations over the centuries, from Garner’s death to the Watts riots to the beating of Angela Davis to “white men their use / of guns on the Indian” (66). The poem directly contrasts the submission to the given order implicit in the Epictetus epigraph as it urges a restructuring of the police’s fraught relationship to the polis: “what you feel is flowing inside to myself it / needs to be that is the only way I could see / that father, that brother it’s me, not my / brother, not my father, all / I would see is white men” (67). These lines recall Whitman’s desire for an eroticized reciprocal boundarylessness (“Translucent mold of me it shall be you!” etc.) as well as the racially conditioned impossibility of this utopia in Langston Hughes’s “Theme for English B,” in which the union isn’t so easy since the white man/teacher has a gun, and, like white Whitman, is “somewhat more free.”

Looking back over the passages I’ve cited thus far, I fear I may be giving the impression that Hosea’s poems clearly communicate a message — or multiple messages — to the reader. One can work, as I have done a bit here, to get that experience, but mostly Hosea dispenses with didacticism and instead invites us to splash around in the sound of these lyric waterfalls. The book — even more deftly than Hosea’s first collection Put Your Hands In — provocatively jams our sensory-motor schemata, our conditioned expectation for rational syntax and logic cashing out in meaningful communication. Here we grind against the contours of language, as for instance in the beginning of “Real Raspberries”:

edge of known stinger stuck

to not in fresh white meat dent

must have been cooked fried

better grilled girl then maps bottom

shelf see women damp their sauce

species in that histories well down

are petrified cushions for thing gathering (26)

Hosea navigates contrasting strata of diction and mood, adopting at times the Psalmist’s grim bewailing tone (see “Little Carbon Book”) while playfully rejecting any notion of a revered lingua Adamica. Be still, these poems never say, and Ashbery’s own description of reading Hosea’s first collection as being “plunged in a wave of happening”[4] is apt for Double Zero as well. One emerges baffled and tingling.

I’ve named some poetic influences (to which one could add Barbara Guest, Clark Coolidge, and Leslie Scalapino), but Hosea moves much more explicitly within the worlds of pop music and visual art. “Tape Hiss” is a wonderfully acute memorial to the now archaic process of making a mix cassette tape — those indestructible, ugly plastic rectangles (punctured by double zeroes), Mercuries of desire during the ’80s and ’90s — and the poem ends with a dizzying mash-up of song lyrics. Hosea has long been immersed in the visual art world, and his book offers rich evidence of his wide-ranging forays. As I’ve noted above, the debt that he owes to the collage work of artists like Schwitters, Rauschenberg, and Villeglé is blatant. Two of the poems in this collection were commissioned by painters, and one by a sculptor. Why is he not a painter? He ponders O’Hara’s conundrum briefly in “Little Blue Book,” offering the conditional snippet: “Were I a painter / With a beautiful advertisement for heaven or hell” (34). Indeed, advertising is a practice Hosea knows well, and we recall here Rancière again, who writes that advertising’s inventors “did not propose a revolution but only a new way of living amongst words, images, and commodities” (25).

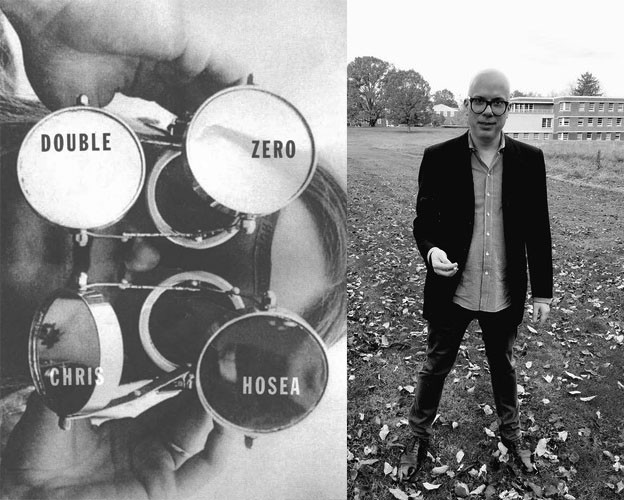

Hosea likes sound too much to be a painter or strictly a visual collagist. These poems, in their sound and vision, imagine a new way of living, hearing, and seeing within our neoliberal war-machine. “Making anything means erasing” (56), he writes. Sure, but his verse testifies not so much to erasure but to the unsayable abundance it keenly samples. And like the late work of the artist/collagist Lygia Clark, a photo of whom adorns the cover of Double Zero, the book demands our collaboration; it refuses to be passively read. In the photo, Clark is holding a six-lensed ocular contraption to her eyes, a series of double zeroes whose membranes slice the plenum from the experiencer. I am grateful for how Hosea’s surprising vision has changed me, and I feel better about the life to come. He characterizes my experience: “I feel differently now you have piqued me” (52).

1. Chris Hosea, Double Zero (New York: Prelude, 2016).

2. Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics (London: Continuum, 2004), 23.

3. Lisa Robertson, R’s Boat (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), 45, 29.

4. From Ashbery’s judge’s citation for the 2013 Walt Whitman Award of the Academy of American Poets.